Afghanistan News: Corruption Still Top Issue After Decades Of War As Taliban Spreads

After four of Fazel Mohammad’s family members were killed in a clash over a land dispute, the Afghan villager from the eastern Kunar province brought his case to government authorities. It was a drawn-out, monthslong process that he said included repeated demands from judges for bribes. Fed up, he sought out an alternative authority: the Taliban. Within days, the militant group brought forward the accused, invoked the Quran and offered a ruling. Mohammad got his land back.

Although Mohammad’s case occurred several years ago, Bilal Sarwary, an Afghan journalist, relayed the story to International Business Times to highlight how corruption, matched by surging violence, has pushed Afghans toward extremist groups, which offer swift justice and critiques of government inefficacy.

"There’s a crisis of government, for the last 14 years, but I haven't seen anything like I'm seeing in the last six or seven months,” said Sarwary, who previously worked for the BBC. “If you’re an Afghan, no matter where you are, in a big city or a village, the obstacle to everyday life is corruption – it's bribes."

Fifteen years after the U.S. propped up a government in Kabul with billions of dollars, bureaucratic corruption in the country remains endemic, according to an in-depth report released Wednesday by monitoring groups Transparency International and Integrity Watch Afghanistan. Those who worked on the study, purportedly the first ever extensive look into Afghanistan's capacity to fight corruption, called on officials to take immediate action, warning that the clock was ticking at a time spiraling violence has drawn into question the competency of the Afghan government.

“By the end of 2016, if major steps are not taken to punish corrupt individuals and remove them from places of power, I think we’ll have [run out of] time to recover,” Sayed Ikram Afzali, executive director of Integrity Watch Afghanistan, based in Kabul, told IBT. “This one year is a defining year... People cannot wait for so long.”

Afghanistan leads among the world’s most corrupt nations — ranking third out of 168 countries, according to a corruption index released last month by Transparency International. Ninety percent of Afghans reported that corruption was a problem in their daily lives, a survey last year found, marking the highest percentage in a decade. Only North Korea and Somalia ranked worse.

The report Wednesday charged the government with failing to deliver basic services, accused officials of lacking integrity and engaging directly in shady private business deals and said the judiciary and police force have allowed crooked individuals to operate with impunity. They called for the establishment of an independent body to combat corruption, the formation of a judicial service commission to select and train new judges and the appointment of officials who have a proven record of fighting corruption.

While the report documents high-level cases, it also raises instances where malfeasance affects Afghans in their everyday life. When people have to go to the hospital, they pay a bribe; when they want to enroll their children in school, they pay a bribe; when they go to the police, they pay a bribe, analysts said. Services are slow, inadequate or non-existent in some areas — a situation that researchers blamed on conflict, corruption and nepotism, which helps unqualified individuals fill influential roles.

"You go to the police, and you don't get any help. You go to the judiciary, and you don't get any help. You are in a situation where you become a helpless, vulnerable citizen of the country," said Rukshana Nanayakkara, regional outreach manager for the Asia Pacific Department at Transparency International in Berlin, who also worked on the report. "This kind of anarchic situation is a thriving ground for insurgents to come back."

Afghanistan has been ravaged by decades of war. Following the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, the U.S. entered Afghanistan and uprooted the Taliban — which it charged with harboring al Qaeda terrorists — and installed a new government. After thousands of American deaths — and many more casualties among Afghans — the Taliban has reemerged as a powerful fighting force.

The extremist group today holds more territory than it has since being ousted from Afghanistan's power centers and has carried out a fresh series of attacks nationwide. The Islamic State group, based in Iraq and Syria, has also gained a foothold in the eastern province of Nangarhar. Last year was the bloodiest year for Afghanistan since 2009 as more than 11,000 civilians were reported killed or injured, the United Nations said.

Experts on the country say part of the problem was an early emphasis on military strategy that lent inadequate focus to state-building. While international aid poured into Afghanistan, bolstering everything from the new government to health projects, much of it was poorly managed and monitored, working only to empower questionable institutions. Although roads are better paved today and girls afforded greater access to education, just 31 percent of the population over age 15 is able to read or write and 36 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, second only to Bangladesh. The continued strife has made it difficult for the government to gather the support necessary to stabilize the country.

The country has seen some measures to push for accountability in recent years, according to Jena Karim, deputy representative in Afghanistan for the Asia Foundation. But she said there was still a long way to go.

"There are a lot of anti-corruption institutions, both at the government level and within civil society," she said. "There are some strides toward transparency and accountability."

"You have a complex environment and it's a tough thing to do," she added.

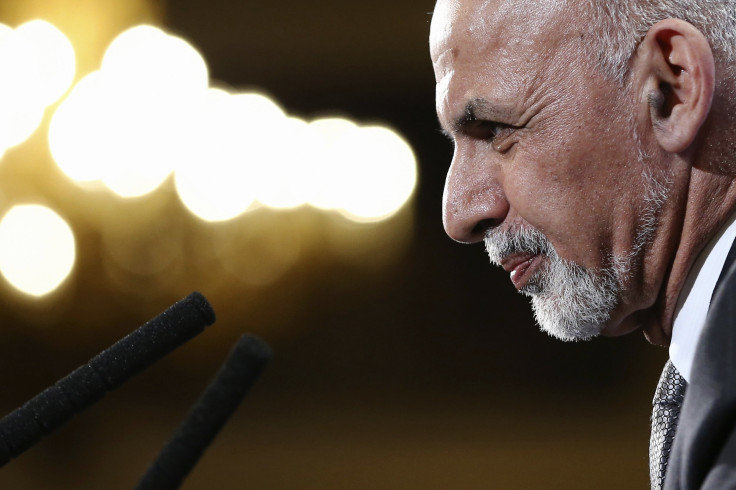

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani has acknowledged and vowed to clamp down on wrongdoing, but progress has been slow as the country's government has been set back by political infighting. The country has had an office for combating corruption since 2008. But it's now part of a national debate: while many once viewed it as a secondary issue to the war against the Taliban, many now see fighting corruption as part and parcel with that battle.

"The argument here is that corruption is destabilizing," Karim said. "There's a strong relation between governance and security, and it's much harder [for extremists] to influence a population that's getting what they need in a fair and just way."

Sarwary, the Afghan journalist, said the stakes couldn't be higher.

On social media, he hints at optimism, regularly posting images of Afghanistan's beautiful landscapes and its ambitious people with the hashtag "#AfghanistanYouNeverSee." He pointed out that Afghanistan has a large population of young people and is rich in natural resources, possibly lending it great potential for the future. The country has also produced a number of prominent athletes, especially in cricket, and thousands of international students.

"I think the Afghan people deserve to have something better. The potential is there," Sarwary said. "If we fail this time, if Afghanistan goes back to the civil war days, I think Afghanistan will be a huge magnet for terrorism, militants, Jihadi groups," he added. "That’s the fear and we’re already seeing the signs.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.