America's Obsession With Health Awareness Days Isn't Making People Healthier

It's May, which means it's once again time for Americans to turn their attention to a slew of health awareness events, including National Stuttering Awareness Week, National Stroke Awareness Month, Heat Safety Awareness Day and Mental Health Month. The public can also look forward to celebrating Hand Hygiene Day, Healthy and Safe Swimming Week, National Teen Pregnancy Prevention Month and Preeclampsia Awareness Month -- after all, they only come around once a year.

May is the most crowded awareness-raising month of the year, rivaled closely by September and October. And although it seems that nearly every nonprofit organization or disease-related group has a designated day, week or month to raise awareness about its cause, there is little evidence to suggest that the onslaught of "awareness" improves anyone's health.

Thirty-seven of the more than 200 official health awareness events listed on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' 2015 National Health Observances calendar occur in May -- from the May 1 kickoff of National Physican Education and Sport Week to World Tobacco Day on May 31. And the federal government doesn’t even attempt to track the countless informal awareness days that are organized by nonprofits or launched on college campuses throughout the country.

When Leah Roman, now a public health consultant in Philadelphia, started her career as a college health and wellness program coordinator in 2006, she felt overwhelmed. Her administration encouraged her to commemorate official awareness days, even when the issue being raised didn’t directly impact the campus community – such as with July's Juvenile Arthritis Awareness Month. As a public health practioner and researcher, this made her wonder whether there was any point in highlighting the days in the first place.

Since then, Roman has teamed up with Jonathan Purtle, a public health researcher at Drexel University, to examine whether there is any scientific evidence to support the notion that America’s obsession with public health awareness days actually improves health or generates awareness.

Together, they have turned up only five evaluations of health awareness days -- none of which were conducted in the U.S. Roman says this lack of scientific evidence is especially striking since today’s public health leaders emphasize the importance of evidence-based programs, and the concept of a health awareness day was first defined in 1979.

Roman has a theory on why health awareness days have become so popular as a means of public health outreach and education. “Many of the people I've met who have organized or participated in awareness days have been personally affected by a disease,” she says. “I think participating in awareness events gives them something concrete to do. Many times when you're dealing with an illness, you feel very out of control.”

Ana Fadich, a certified health education specialist and vice president of the Men’s Health Network in Washington, D.C., says that annual awareness events help her organization reach out to men and their families to talk about issues such as prostate cancer that often go ignored. Her staff is gearing up to launch their biggest campaign of the year: Men’s Health Week, June 15-21 – the week leading up to Father’s Day -- and Men’s Health Month, in June.

For Men's Health Month, the network compiles a nationwide calendar filled with health-related events and activities, from free depression screenings in Florida to a 5K run in Los Angeles to raise money to prevent prostate cancer. The organization also encourages men and women to wear blue on Friday, June 19, and upload photos to social media with #showusyourblue. Fadich estimates that they reach “hundreds of thousands” of men during the month.

That's a lot of events, and Fadich's staff also occasionally supports events organized by other groups.

“People are overwhelmed,” she says. “We hope that we're not getting lost in the jumble.”

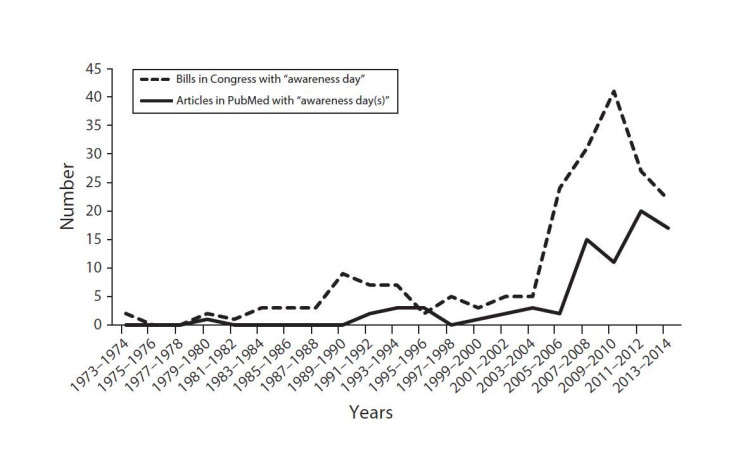

Tara Broido, a spokeswoman for the Department of Health and Human Services, says that the national calendar of health awareness days has become healthfinder.gov’s most popular service for public health professionals. The craze has taken hold despite the fact that these programs lack scientific legitimacy: Since 1973, 202 awareness day bills have been introduced to Congress and the vast majority – 71 percent – were submitted in the past decade. And the number of articles listed in PubMed, a database of scientific and medical literature, that refer to "awareness day(s)" seems to be growing, as well.

Purtle points out that raising awareness or informing a person about a disease does not necessarily mean that they will take any action to mitigate the risk of contracting it. For example, a 2013 study by researchers at Brigham Young University tracked tweets about breast cancer during Breast Cancer Awareness Month in October and found that while there were plenty of tweets about wearing pink, relatively few encouraged women to receive mammograms.

“Awareness can be a first step to something that is meaningful,” Purtle says. “The knowledge by itself isn't really going to do anything.”

Roman argues that awareness is a vague concept that is hard to measure and doesn’t lend itself to the sort of rigorous scientific evaluation on which public health should be based. Determining what makes a successful awareness day is a bit of a murky concept. She says one legitimate goal may be to raise funds with the aim of using that money to later implement programs that will improve public or personal health. “The main issue is that the goals are typically not stated, or if the goal is stated, it just says 'raising awareness,' which is really, really vague,” Roman says. “If I don't have a goal, I can't measure it, and if I can't measure it, I can't figure out if it worked.”

While this ambiguity may make it easy for an organization to claim that it successfully raised awareness, that declaration is not useful for demonstrating real improvements to public health.

Both Purtle and Roman say that if health awareness days are used at all, they should be launched with clear metrics in place to measure the impact on personal health or other stated outcomes. For example, Roman and Purtle have found one study that showed that the number of calls to a smoking helpline was five times higher than average on a No Smoking Day in the U.K. On another awareness day in South Africa, about 700 people who were screened for cardiovascular problems learned that they had at least one risk factor. Such metrics could guide future efforts and help shape health awareness days into a meaningful tool.

The team also says organizers should share the results with the public health community so the groups can learn from one another. In the absence of such research, Roman recommends that organizers consult the National Cancer Institute’s guide for creating evidence-based health communication programs as a starting point.

Still, Purtle points out that health awareness days tend to ignore the fact that people often do not have full control over their personal health due to environmental and social factors. He says it might be more useful to channel the collective energy poured into health awareness days each year into advocating for specific policy changes that could improve the healthfulness of the nation’s food supply or provide access to better services to marginalized communities.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.