Apple Inc.’s ResearchKit Enables iPhone Parkinson’s Disease Study To Release Treasure Trove Of Data

Can the iPhone cure disease? That’s the hope behind a landmark study of Parkinson’s disease released Thursday that used Apple’s iPhone to track the progression of the disease among 9,500 people — without the researchers ever seeing a patient in person.

The study, conducted by nonprofit medical research group Sage Bionetworks and Rochester Medical Center with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, is one of the first big applications of Apple’s ResearchKit, a set of software applications that make the iPhone a tool for medical research.

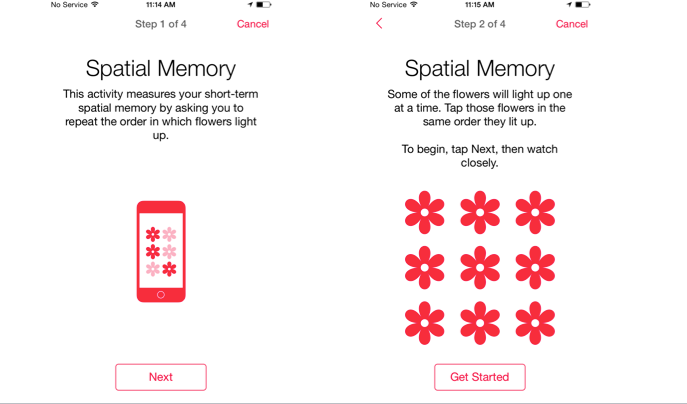

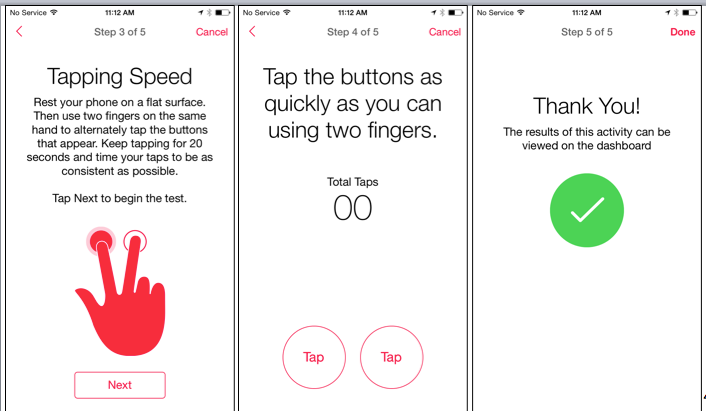

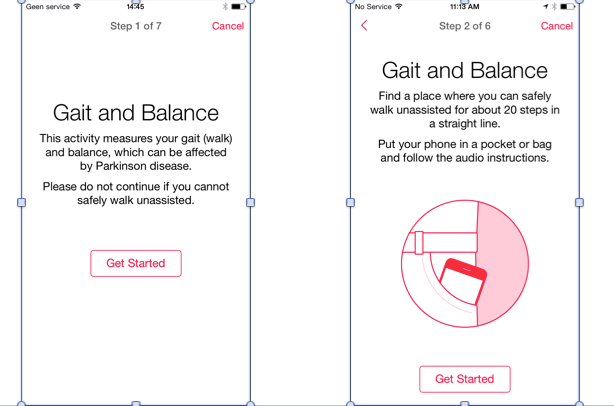

Participants in the study volunteered to download an app and perform daily tasks that measured dexterity, short-term memory, balance and even speech, all performed with the help of the iPhone’s built-in sensors, such as its accelerometer, microphone and touchscreen. The result is a data set that includes millions of information points gathered over a six-month period beginning last March.

“If you can track an individual on a day-by-day basis, you can see variations in symptoms of 20 to 40 percent even though you only saw a small percentage change over a six-month period,” said Dr. Stephen Friend, president of Sage Bionetworks.

Sage made its findings available widely Thursday to researchers studying the disease and detailed the scale of the project in review journal Nature Scientific Data. For researchers studying Parkinson’s disease, gathering as much data as possible is important in understanding how to treat the symptoms, which afflict 7 million to 10 million people worldwide, causing tremors, speech problems, memory issues and ultimately death.

The study is notable for its size. Traditionally this kind of medical research is done locally in groups that consist of 20 patients on average who travel to a hospital or other physical sites. The iPhone data set, made possible by Sage’s mPower app, includes millions of information points gathered from participants who downloaded the app.

In a preliminary examination of the data, Sage also spotted some patterns between medication intake and symptoms in participants, which eventually could be used by researchers to find better ways to treat the disease.

Performing a study via an iPhone without any direct human researcher action also poses the dilemma of dealing with occasional participants who sign up and claim they have Parkinson’s even if they do not. But with more than 9,000 participants, it’s much easier for researchers to spot the symptoms common to patients suffering with the disease and those who aren’t affected. Furthermore, the research study wasn’t limited to those with Parkinson’s. Some users were part of a control group.

Participants were also asked whether they wanted to share the data only with Sage Bionetworks or whether to make their data more widely available to third-party researchers. To protect the anonymity of participants, Sage kept their emails and names encrypted and separate from the research data.

While that may be a plus for privacy-minded users, it also prevents researchers from speaking to individual patients for additional feedback. Despite the limitation, it does have its advantages — namely, a larger amount of data that can be gathered on a daily basis via the iPhone app whereas an in-person study would yield results on a monthly or six-month basis through a smaller group of participants.

But with such a large data set available to researchers also comes concerns about privacy. “Even if a researcher has deidentified a health data set, it can be reidentified,” said Pam Dixon, founder of the World Privacy Forum. “It’s kind of a fake promise. You have to add other rules to protect people.”

That said, the responsibility mainly falls on the researchers themselves since Apple only provides ResearchKit to help developers and researchers build out these studies. None of that data is stored in its servers.

“ResearchKit is a perfectly good system in terms of privacy because Apple doesn’t see the data in it,” said Dr. Adrian Gropper, chief technology officer of patient privacy rights. “Apple has the best privacy policy you can have. Apple will not see your data.”

While the study is making the data available for research use, it’s not as easy as just hitting a download button. Researchers interested in the full data set and results are required to sign up for Sage Bionetworks’ Synapse service, have their accounts validated by the Synapse compliance team, submit a statement declaring their intended use of the data and agree to the terms of use for each data set. Researchers who accept the terms agree not to attempt to reidentify research participant data for any reason or use it for commercial purposes. Ethical oversight of the study was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board.

Researchers using the iPhone in their studies include Mount Sinai, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Stanford Medicine, among others. In addition to Parkinson's disease, the studies conducted also examine autism, epilepsy, melanoma, asthma, diabetes, breast cancer and heart disease.

While Sage's Friend sees ResearchKit as a powerful tool for researchers, he also says it’s just getting started. “I think this is the pre-Model-T,” Friend said. “We’re not driving around in a Tesla right now. But we’re going that way.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.