Brussels Airport And Metro Bombings: Could EU Intelligence Sharing Have Stopped Belgian Terror Attacks?

As citizens of Brussels grappled with the aftermath of a deadly terror attack Tuesday, security and defense experts looked closely at what made the Belgian capital, which has been on high security alert for months, susceptible to the fatal explosions. The latest attack on a European capital city came just one day after French and Belgian officials met to affirm their dedication to working together to fight extremism as terror threats spread in Western Europe.

But security experts said unless the European Union fixes the apparent dearth of intelligence-sharing among its member countries, the continent's major cities will continue to be exposed to similar attacks in the future.

“This is a classical case where we see the importance of intelligence cooperation not just internally but externally,” said Eelco Kessels, London Office director and senior analyst for the Global Center on Cooperative Security, a security consultancy. "The most headway on this front is still made by bilateral or multilateral cooperation between countries.”

European nations have often been unwilling to freely share intelligence with one another unless there is the promise of getting something in return, Kessels added. This back-scratching approach to intelligence across European borders, he said, has slowed progress in fighting terrorism in the EU.

Despite recent border closures amid an ongoing refugee crisis, free travel is still at the heart of modern Europe, and the 1995 Schengen agreement that created visa-free travel between member states has facilitated radicalized EU nationals to pass between countries unchecked.

“We have, in effect, no European intelligence system, but we do have a Europe that with the Schengen agreement has erased national borders,” said Christian Harbulot, the director of the Ecole de Guerre Economique, a French institution of higher learning focusing on business and security. “It’s a contradiction.”

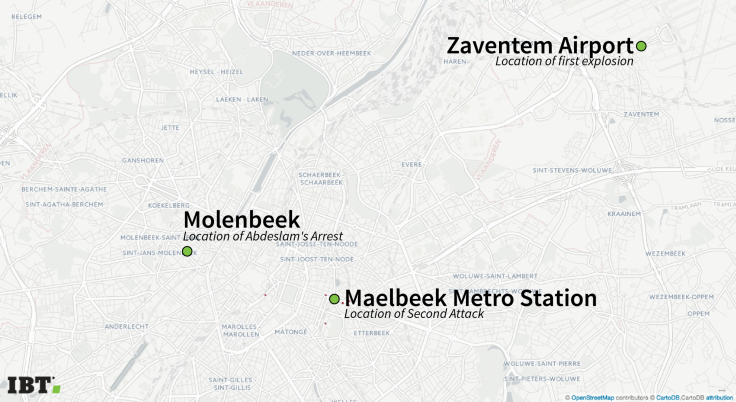

Tuesday’s attacks in Belgium began around 8 a.m. local time in the international airport of Zaventem when two explosions rocked the entrance to one of the main terminals. Authorities have now determined that one explosion was caused by the detonation of a suicide vest and another was triggered remotely, possibly from inside a suitcase. Nearly one hour later, another blast tore through the front cars of a subway as it came into the Maalbeek station in central Brussels, just a few yards from the EU headquarters building. The terror organization known as the Islamic State group, or ISIS, claimed responsibility for the attacks , which killed at least 31 people and injured dozens more.

Brussels has been on a high security alert since the mid-November terror attacks in Paris, also claimed by ISIS, left 130 dead and dozens more wounded. More than half of the terrorists involved in those attacks were either Belgian-born or had Belgian nationality and traveled freely across the border between France and Belgium before carrying out the deadly assaults on cafes, restaurants, a stadium and a concert hall.

Tuesday's attacks on Brussels occurred just days after law enforcement captured Salah Abdeslam, believed to be one of the last living terrorists involved in the Paris attacks. Abdeslam was born and raised in the Molenbeek neighborhood of Brussels, a primarily Muslim, low-income area. He was discovered in the apartment of an acquaintance in Brussels Friday following a four-month manhunt.

Critics of Belgium’s border security and law enforcement have scrutinized how long it took to capture Abdeslam as well as the fact that the Paris attackers planned their assault relatively undetected by Belgian authorities. The problem of detection goes beyond national borders, according to experts, however, and stems from a systemic failure to share intelligence internally and externally with other European nations.

From an internal point of view, Belgium law enforcement and intelligence services exist across multiple agencies, including police services, security agencies, national guard as well as the security forces for major international institutions that call Brussels home, such as the European Union and NATO. Analysts have criticized a lack of internal coordination, where disconnects often exist between Belgian intelligence agencies, such as the civil State Security service and the General Intelligence and Security Service, its military counterpart.

Cultural and symbolic factors may have also played a role in making Belgium a target. The country, like France, has a large, frequently disenfranchised Muslim population, some members of which have been seduced by Islamic extremist groups. The symbolic importance of Brussels as the capital of the EU and the seat of NATO may have also made it a choice target for terrorists looking to strike at the heart of the European project.

Obstacles facing streamlined intelligence-sharing on an external level stem both from administrative hurdles as well as a reluctance on the part of individual countries and agencies, analysts said. National authorities, including the federal prosecutors in France and Belgium in a meeting Monday, have repeatedly stated their desire to share information across nations. But when it comes down to releasing sources or techniques, agencies frequently balk at giving their private information away.

“It’s a cultural thing and it’s quite deep-seated,” said Ewan Lawson, a senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, a British security think tank. Intelligence agents are trained to build relationships with sources and gather information with the utmost discretion, and so asking them to suddenly expose that information goes against everything they were trained to do.

“I don’t think there’s enough trust between those agencies across Europe,” Lawson added, “And trust is a key word in all this.”

In order to prevent future terror attacks like those in Paris and Brussels, European nations need to cooperate on security, in the form of a shared database or even a continentwide intelligence agency similar to the CIA, policy analysts said.

“What we would need is to have a more advanced form of collective sharing that in the moment something happens, you would sort of raise the curtains that you would otherwise have down … so actors would have the full information that is available,” said Josef Janning, a security analyst and director of the Berlin office of the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank with locations across Europe.

The vision of a shared database or service is still far off, according to Janning, who pointed to the entrenched traditions of secrecy and national sovereignty in each European country.

“It is the institutional mistrust of intelligence services that will keep them from fully cooperating," he said, adding, "These people are simply not made for openness."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.