Burundi Elections 2015: President's Third Term Called Unconstitutional As Country's Vote Is Held

Citizens of Burundi awoke to the sounds of gunshots Tuesday morning, signaling the start of Election Day. In most democratic nations, elections often offer hope. They promise an opportunity for change, for the chance to start over with a new leader. But not in Burundi. For citizens there, they knew who would win the 2015 presidential election, and they feared the potential violent consequences that could occur.

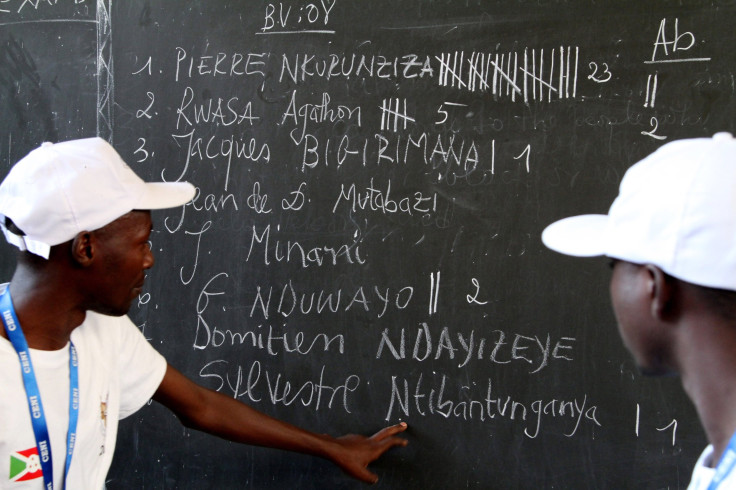

President Pierre Nkurunziza, 51, was running for his third term as the African nation’s leader, and every opposition party had dropped out of the election in protest. Nkurunziza has been president of Burundi since 2005, but a third term for the president was in clear violation of Burundi’s Constitution. Opposition groups said that running for a third presidential term violated the Arusha Agreement, which ended Burundi’s brutal civil war in 2005 and stipulated a two term limit for the nation’s highest office. Nkurunziza argued, though, that since his first term was elected by ‘indirect suffrage’ by the National Assembly and Senate and not by general election, he should be able to run again.

“Burundi has come a long way to get to the point where they would have a president for only two terms,” said Steve Howard, director for International Studies at Ohio University and a specialist in African Studies. “Nkurunziza is playing the ‘big man’ role in Africa, which is a pattern we saw and had hoped was dying down. There are a number of leaders who act like the big cheese and feel that they are in complete control of the country and [think] that the country cannot survive without them.”

Last month's parliamentary election, which had to be pushed back from June 29 due to civil unrest, was projected to see around 3.8 million Burundians cast ballots for 100 lawmakers. Instead, the country saw a low voter turnout, largely because of a boycott by 17 opposition groups. The National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy -- Nkurunziza's ruling party -- won a sweeping victory. The party is an ex-rebel Hutu group that represented the excluded majority population of Burundi but has since morphed into something more. One of the opposition groups that boycotted the elections included Democratic Alliance For Change, which is comprised of 12 opposition parties. The opposition groups said that they were boycotting the parliamentary and presidential elections because the elections are rigged, unfair and illegal.

mark your history books: in a few hours, a fully fledged dictatorship will be born.

a dark, menacing cloud over Africa.

#Burundielections

— Ketty Nivyabandi (@kettynivyabandi) July 20, 2015"If the government maintains the status quo and organizes the presidential poll, we will not participate in that masquerade since the results are already known," said Leonard Nyangoma, the spokesman for the Democratic Alliance for Change, at a news conference on June 23 in the capital, Bujumbura, IRIN Africa reported.

Opponents have accused Nkurunziza of using intimidation tactics to secure his place in power, and dozens of opposition group members -- including a leader -- have been killed or mysteriously disappeared in the months leading up to the elections. Since April, 170,000 Burundians have fled the country to seek refuge in neighboring countries.

International support for the election has essentially diminished. On Tuesday, the U.S. said Burundi’s elections lack credibility and by pressing ahead, the government "risks its legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens and of the international community." The European Union suspended its election observer in Burundi due to concerns over its restrictions on the independent media, its violence against demonstrators and use of intimidation tactics.

The African Union also did not observe Burundi’s legislative elections last month. "Noting that the necessary conditions are not met for the organization of free, fair and transparent and credible elections...the AU commission will not observe the local and parliamentary elections," the African Union said in a statement. In May, Gen. Godefroid Niyombare, the former head of Burundi’s intelligence system, attempted to lead a military coup but failed.

There have been small but steady inclines in Burundi over the past years, however. Since Nkurunziza has been in power, there have been a few improvements in the former war-torn nation. The country doubled its tax receipts between 2010 and 2014, moved to paying nearly 80 percent of its recurring expenditures from domestic revenue and the Arusha Agreement and the 2003 Pretoria Protocol on Political and Defense Power Sharing established the principal of a 50-50 ethnic quota system for the new “National Defense Force." The country has also become a major force in peacekeeping across Africa, with around 6,000 troops deployed with the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and units serving with United Nations missions in Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, South Sudan and Sudan.

The results of the controversial election Tuesday could be a tipping point for Burundi and cause violent protests, however. The country is still one of the poorest in the world, with 66.9 percent of the 10.48 million-person population living below the poverty line. The country also has a dark past: A 12 year civil war from 1993 to 2005 between the country’s two ethnic groups -- the Hutu and Tutsi -- left 300,000 people dead. The Arusha Agreement that Nkurunziza was accused of violating brought peace to the war-torn country.

The ethnic dimension of the unfolding electoral crisis in Burundi is something that cannot be ignored, said J. Peter Pham, the African Studies Director at the Atlantic Council, a think tank in the field of international affairs. Pham said it was important to note that Nkurunziza was the first Hutu president of Burundi to finish his term. He added that one of the most prominent leaders of the protests against the president, Pacifique Nininahazwe, founder of the nongovernmental Forum for Conscience and Development, is a Tutsi. Sylvere Nimpagaritse, the vice president of the Constitutional Court -- who went into exile rather than recognize Nkurunziza’s candidacy -- is also a Tutsi.

“We (the U.S.) are forty years from our civil rights movement, but we still have racial tension in our country,” said Pham. “Our struggle for civil rights in this country is not close to being as bloody as Burundi’s was, and they are only ten years out from it.”

Pham said that whether or not Nkurunziza should be able to run for a third term is a legal question that should be sorted out among the Burundi people. However, even if it were legal for Nkurunziza to run for a third term, whether or not it would be a good idea is an entirely different issue.

“The overarching motivation is good; that leaders shouldn’t overstay their limits,” Pham said. “Africa consists of 54 different countries, each with a different system, but having a cookie cutter approach and applying it blindly across the continent is not helpful.”

The results of the election were expected to be announced later this week, but Howard said he expected that 95 percent of the votes will be for Nkurunziza.

“It’s very unfortunate,” Howard said. “I think some countries in the neighborhood will try to organize a reconciliation meeting and I think international organizations will try and mediate as well, but Burundi is in for some degree of hard times. It’s a poor country -- one of the most densely populated countries in the world -- and this (the election) is a reason for a lot of tension.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.