Businesses That Copy Oscar Dresses Face Counterfeiting From Chinese Websites

Omid Moradi will gather with his family for dinner and snacks this Sunday while they all watch the Academy Awards, as they do every year.

His four daughters love to watch the parade of red carpet dresses, but they're not the only ones who will be focused on fashion as the glamorous event unfolds.

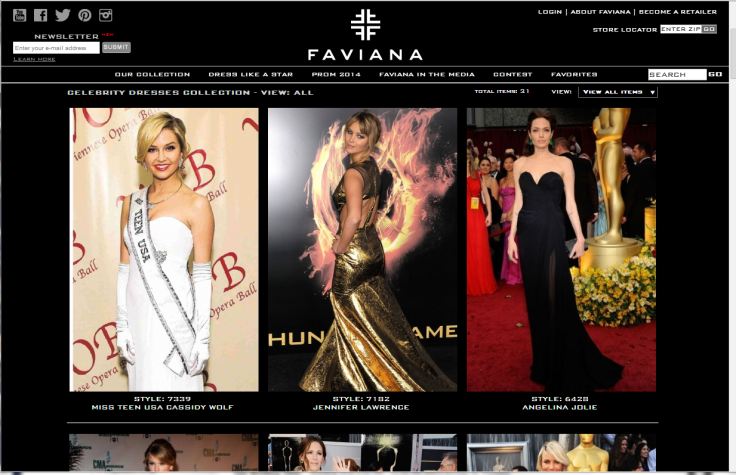

As the CEO of Faviana, a Manhattan-based designer gown shop, Moradi has a lot to think about besides which movie will win Best Picture. The 22-year-old business has made a name for itself offering "bling on a budget," designs inspired by celebrity-wear, catering to customers who want to look like a million bucks without paying more than a couple hundred.

“We’re a family-owned business. My mother is a director of design,” he said. While watching the red carpet coverage, “we’re all texting back and forth with other people on our design staff,” he said, adding that they’re always thinking of what they have designed already that’s similar.

The copycat strategy in fashion is widespread -- and completely legal. In fact, economists say that knockoffs even bolster the industry since lower-priced versions act like advertisements for the real thing. But in recent years, Moradi has found himself a victim in an expanding game of copycat.

“Those Chinese companies; they use our trademark name and our pictures and claim they’re going to sell our dresses,” he said. “An uneducated customer gets trapped.”

Moradi is just one among many U.S. retailers facing competition from overseas sites that steal their logos and photos to sell lower-quality products online. But they’ve been making progress in the fight, using legal action to shut down more than 1,000 operations in China in the past few years.

The Oscars mark the beginning of peak season for the imitators as younger customers hunt for the perfect prom dress inspired by their favorite stars. Each year Faviana makes a splash turning out Oscar replicas -- exact copies of dresses worn by the stars -- within days after the big event. They’re really more of a public relations stunt, as it typically takes more than a month to complete a dress.

Moradi and his team are always following trends so they can predict what colors, styles and details will be popular on the red carpet. Watching the Academy Awards is "kind of a feel-good night for us. Many times we’ll say, ‘Wow, we’re really on target,’” he said.

Ideally, Moradi’s customers see a dress during an awards telecast, and then go to the “Dress Like A Star” section on the Faviana website. There, they can scroll through dresses inspired by what celebrities wore at awards events. While designer pieces can cost upwards of $3,000 to $4,000, Faviana dresses run from $300 to $700.

Some of their versions are so similar that they’re mistaken for the real thing. Two years ago, Kim Kardashian wore a Faviana dress to a film festival in Monte Carlo. Days later she was featured in a magazine’s “Who Wore It Best” section, next to Eva Longoria wearing the designer version.

“It’s accessible luxury,” Moradi said.

The phenomenon is widespread in the U.S., and there’s been a general tolerance for it. Though some big brands have pursued legal action, they generally look the other way -- maybe because this kind of imitation can actually benefit them.

“People buying knockoffs aren’t the same people who would buy the thousand-dollar versions,” said Christopher Sprigman, a New York University law professor, and co-author of “The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation.”

In the book, he and co-author Kal Raustiala explain how, in certain industries, like food and fashion, imitation is actually a good thing because it gets people thinking about the original designer.

Retailers from family-owned Faviana to the juggernaut chain Forever 21 have soared to success on the imitation business model, serving the market with fashionable clothes for a fraction of the cost, and generating thousands of American jobs in the process.

But the China problem looms large.

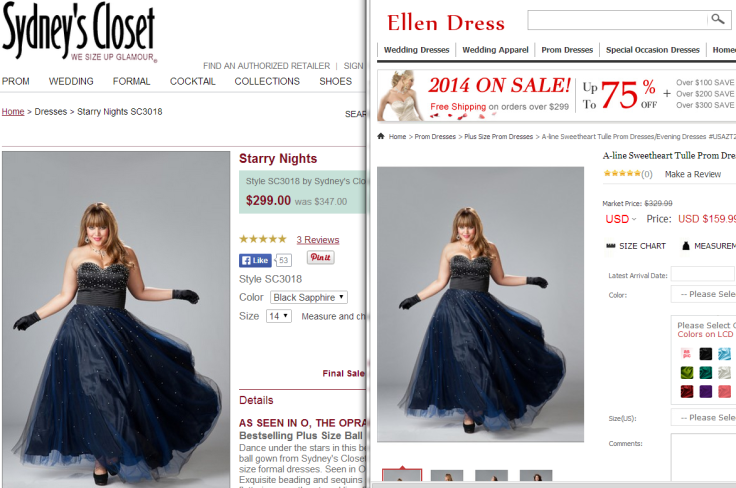

Phyllis Librach, founder of Sydney’s Closet, a plus-size dress designer and manufacturer in St. Louis, had a global following and steady growth — until a few years ago, when she noticed an abrupt downward trend in traffic to her website. A quick Google search for “plus-size prom dress” turned up dozens of companies based in China with strange names that dominated results. But she saw something that was even more upsetting.

“I was shocked to see these companies selling Sydney’s Closet original designs using our copywritten photographs,” said Librach.

Sometimes, the sites even added their own watermark to the photos.

Librach, a journalist before she got into fashion, decided to investigate and ordered one of her designs from a Chinese site.

“When it arrived, we couldn’t even recognize it,” she said.

“It was a total bait-and-switch. Our shimmer chiffon fabric had been replaced with a thin, cheaper version with no sparkle.”

The color was faded, the seams were puckered and the details looked “sloppy,” said Librach. It was also a few inches too small.

Around the same time, Sydney’s Closet started getting calls from frantic customers facing fashion emergencies after making similar purchases. Often in tears, they shared disaster stories about ordering a dress that never came or one that arrived but didn’t look or fit right. Many of them had no idea they weren’t ordering from Librach’s store.

Likewise, Roanna Rose, owner of Missouri-based TJ Formals, started noticing a drop in her website traffic around 2009.

“My business depended heavily on the Web aspect,” she said, adding that online purchases used to account for more than 90 percent of sales – the rest come from her retail shops, located in a relatively small town with little foot traffic.

Even with a slow economy and increased competition, she estimates her business has lost at least 30 percent in recent years thanks to counterfeiters.

“People are getting more knowledgeable, but it’s a problem for younger people, especially girls looking for a prom dress,” she said. Often 16- and 17 year-olds are on a budget, but they don’t know where to start looking.

In 2011 Rose and others like her organized to form the American Bridal and Prom Industry Association (ABPIA), a group of retailers focused on taking legal action against the counterfeiters. At that time, she had compiled a list of 150 illegitimate sites; today the list is up to 3,000.

ABPIA has been working with LevelPlay, a tech company that uses Web crawlers to track down counterfeiters with a specific algorithm that finds suspicious sites and cross-checks the images against those of legitimate retailers.

“There are thousands of counterfeit sites in every product category,” said the company’s founder, Daniel Walling. In the first stage, a quick search for keywords like “cheap,” and “discount” along with “dress,” “wedding,” “prom,” and other terms can effectively pinpoint possible counterfeiters, he explained.

After finding the sites, the ABPIA takes legal action.

On Feb. 10, the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey sided with the ABPIA and entered preliminary injunctions against more than 1,000 suspicious retailers, freezing their accounts. Though the sites are based in China, most use American payment systems such as PayPal for transactions.

“We’re guessing there’s about $1 million of counterfeit money frozen in PayPal,” said Steve Lang, ABPIA president and CEO of Mon Cheri Bridals LLC.

It seems like a lot, but it’s just the tip of the iceberg. He conservatively estimates that more than 600,000 counterfeit units were sent to the United States last year.

“It’s costing jobs,” he said, though he couldn’t put an exact figure on it.

Adding insult to injury, Lang said, “these guys are shipping dresses and labeling them as gifts,” which means they don’t have to pay taxes. “I couldn’t bring a button into this country without paying duty.”

But things are changing, with more fashion businesses joining the fight.

“Federal district courts around the country, but most notably in New York and other East Coast venues, have seen an increase in recent years of lawsuit filings by manufacturers – both large and small ones – against websites hawking counterfeit and ‘knockoff’ goods,” wrote Craig Hilliard, the lawyer representing ABPIA and others in a class action suit, in an email to IBTimes.

“These lawsuits are more difficult to pursue than the prototypical trademark infringement case, because the defendants are usually overseas,” he said, adding that some even have fictitious names.

Court filings refer to more than 1,000 defendants and name 16 sites specifically including the following: moncherybridal.com, happyweddingdresses.com, lafemmedresscheap.com, weddingdresspricesale.com and beautifulpromgowndress.com – many of which are now shut down.

None of these companies responded to request for comment from IBTimes.

Experts say a good way to determine a site’s legitimacy is by checking its origin. For instance, it might be a red flag if one company has an American-sounding name but is based in China. Price and selection can also be tip-offs. If a dress costs $400 at a retailer and just $60 online, or is available in more 50 color options, it’s probably not legitimate.

So anyone who wants an Oscar dress for less should remember that old adage: If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.