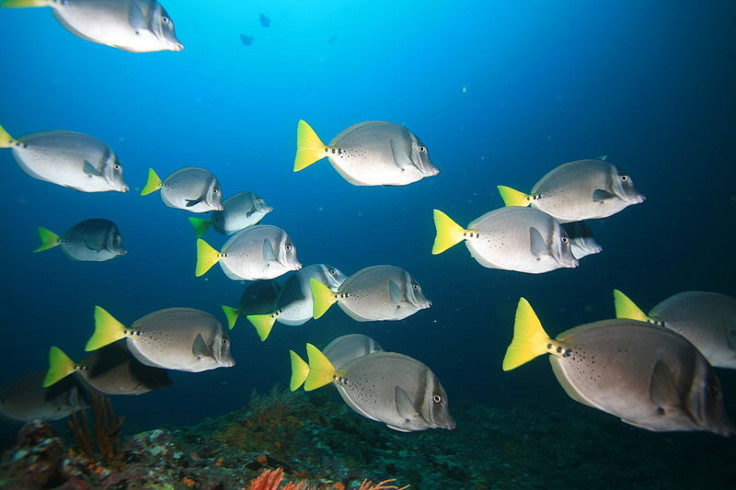

Caribbean Coral Reefs Could Vanish In 20 Years Due To Overfishing, Tourism: Report

Most of the Caribbean coral reefs could be wiped out because of the declining sea urchin and parrot fish populations, as well as climate change, according to a new report from conservationists.

A comprehensive analysis of the report, dubbed Stats and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs: 1970-2012 and assembled from 35,000 surveys taken over those decades, found that coral reefs throughout the Caribbean have been reduced by 50 percent since 1970. More than 90 scientists from the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network participated in the analysis and found that the decline could continue until there’s simply nothing left, reports the Guardian. The report was published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Much of the problem can be blamed on the sudden decline of grazing life, most notably sea urchins and parrot fish. These herbivores help maintain life on coral reefs through the world by eating much of the algae that takes up much of the sunlight that reefs need to survive. Grazing populations alone are not enough to keep a reef alive, but they do provide an important balance against otherwise dangerous levels of plant life, according to CoralScience.org.

A mysterious disease devastated much of the sea urchin population in the early 1980s, while overfishing and unregulated tourism has rendered the parrot fish nearly extinct through much of the Caribbean. Researchers compared reefs where parrot fish and other grazing species were not protected and found that the reefs had greatly suffered compared to where fishing restrictions are in place. Reefs in Bermuda, Bonaire and the U.S. Flower Garden Banks are much healthier than in areas like Jamaica, the U.S. Virgin Islands and the Florida reef tract from Miami to Key West, the Guardian reported.

“The rate at which the Caribbean corals have been declining is truly alarming,” Carl Gustaf Lundin, the director of IUCN’s global marine and polar program, told the paper. “But this study brings some very encouraging news: The fate of Caribbean corals is not beyond our control, and there are some very concrete steps that we can take to help them recover.”

Those essential steps include protecting against overdevelopment along coastlines, as well as preventing coastal pollution and tourism. Scientists combed through the reefs and ocean floor and found a plethora of discarded fishing nets and trash, with dead parrot fish trapped beneath the objects.

The Caribbean is home to 9 percent of the world’s reefs, although only one-sixth of the reef that was originally there is still in place. Countries in the Caribbean and elsewhere around the world rely on the underwater plant life for a variety of economic reasons, but many are proving difficult to protect – even Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is at risk due to overfishing and coastal development.

“Even if we could somehow make climate change disappear tomorrow, these reefs would continue their decline,” Jeremy Jackson, lead author of the report and a IUCN senior adviser, wrote. “We must immediately address the grazing problem for the reefs to stand any chance of surviving future climate shifts.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.