Chris Christie Sandy Recovery: As Presidential Campaign Falters, New Jersey Governor Slammed For Hurricane Response

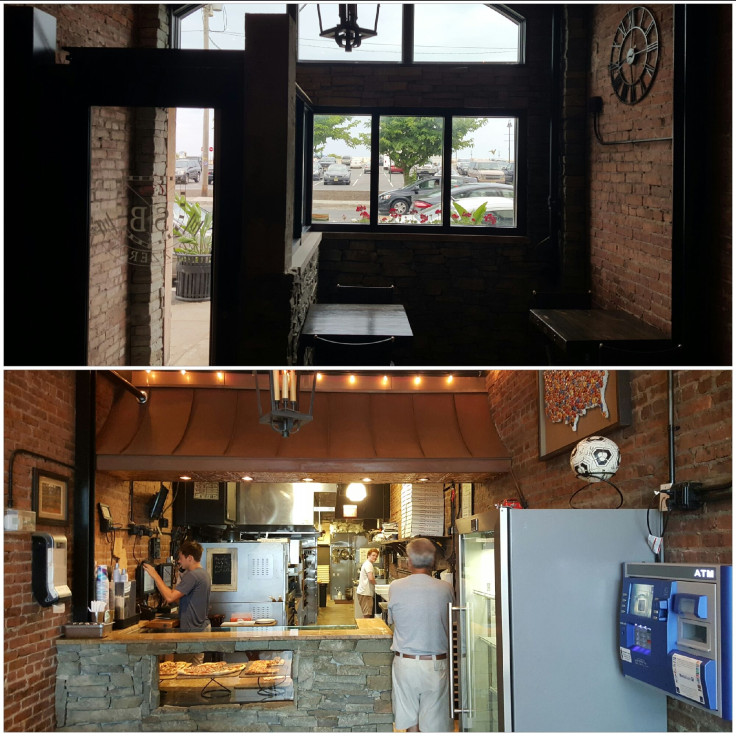

SEA BRIGHT, New Jersey — When Superstorm Sandy swept through the New Jersey coast in October 2012, Cano Tezza's pizzeria was fleeced. Everything, including the huge, heavy pizza ovens in the middle of the long and narrow shoreside shop, were missing the next day, lost somewhere amid the beach that had moved into town. It wasn’t the first time that a storm had wreaked havoc on Tezza's shop or the town, and it won’t be the last.

In the aftermath of the storm, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, a 2016 Republican presidential hopeful, was praised for his response. He hugged President Barack Obama, a Democrat, against a backdrop of debris and wreckage, relentlessly toured damaged communities and started the long process of getting people back into their homes.

But while all of that looks good on TV newscasts, critics of Christie’s leadership in the nearly three years since the storm say the governor failed to start necessary, albeit difficult, conversations with shore-area residents that could have moved the state on a path toward a less vulnerable coastline. With Christie's presidential campaign faltering as the GOP candidates prepare to take to the stage for the first Republican debate of the 2016 campaign Thursday night, Christie's hurricane recovery efforts might help explain why voters across the country, including in his own state, don't seem eager to view him as a leader.

“In terms of nuts and bolts, the thing that a number of us who have worked in this field in [New Jersey] for many years seem to agree on is that there were a lot of missed opportunities in the recovery,” said Mark Mauriello, director of environmental affairs at Edgewood Properties, a New Jersey real estate development company. Mauriello is a geologist and a former commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, a position to which he was promoted while Christie’s predecessor -- Jon Corzine, a Democrat -- was in office. One of the biggest problems, Mauriello said, are policies in the state constitution that allow storm-damaged communities to rebuild immediately and in the exact same spot.

Christie wanted to take a leadership role and show he was helping people, but “he was sort of blinded by the goal of rebuilding quickly,” Mauriello said. “Unfortunately, while doing this there was not a lot of thought on the appropriateness of this rebuilding strategy.”

Communities like Sea Bright, located on a narrow strip of land between the Navesink River and the Atlantic Ocean, are frequently flooded and hammered by the unforgiving temper of the open sea. There are no real long-term solutions to the problems posed by communities like Sea Bright, experts say, save one: to honestly evaluate whether or not some people and businesses should be moved into new homes, further inland and away from high-danger flood zones where they are repeat victims of devastating floods and severe weather. Not every community needs to move, but the conversation should be had, environmentalists argue.

Christie, however, has made few efforts to entice some residents away from the shore. One state program known as the Blue Acres Buyout allocated $300 million for residents who wanted to move away from flood-prone areas. As of October 2014, 200 homes had been bought through the program and 500 offers had been made. More than 74,000 flood insurance claims were submitted in New Jersey after Sandy.

"In New Jersey, and it’s different in some other states, there’s not been very much success with community-level solutions like changing the zoning or doing mass buyouts of properties," said Clinton Andrews, a professor of urban planning and policy development at Rutgers University. "Instead, the most common response has been for individual property owners, if they can afford to, is to elevate their house in the same spot as it used to be."

Dunes To Keep The Waves Away

Superstorm Sandy crippled the Northeast when it struck in 2012, causing an estimated $65 billion in damage, destroying more than 650,000 homes and leaving as many as 8.5 million people in 21 states without power. The storm's impressive size -- it extended 500 miles from its center -- caused catastrophic flooding in New York City and much of New Jersey.

Following Sandy, New Jersey adopted guidelines that pushed residents to rebuild or lift houses one foot above federal flood guidelines. Other states, like New York, chose to adopt higher levels to prepare for rising sea levels, a phenomenon that is occurring and well documented.

Instead, Christie’s administration focused mainly on dune development, coastal fortification and elevating or rebuilding homes. No matter the sea-level or future storm forecast, houses destroyed by Superstorm Sandy get to go where they were before. On their own, these policies provide some relief from a battering Atlantic, but ultimately require continual replenishment and maintenance that will become incredibly costly. Sand erodes with tides and time.

Critics see this focus as a stop-gap measure geared less toward solving long-term problems and more toward making Christie look good on election days. Many also say Christie has avoided responding to sea level rise on the coast.

"The governor can play an enormous role. Chris Christie has so far not engaged in addressing the issues of sea level rise head-on," said David Kutner, recovery planning manager for New Jersey Future, a nonprofit that works with local communities to reimagine recovery and rebuilding policies. "I think he could be much more present in these discussions. He could be guiding this. Any governor of any state … [has] tremendous control over how a state responds to these kinds of statewide, huge issues."

The costs of rebuilding and mitigation efforts are not shouldered solely by New Jersey residents. In addition to the $60 billion in Federal Emergency Management Agency aid doled out following Sandy, the nation's taxpayers foot the bill for the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) required of people who don’t outright own their homes in FEMA flood zones. Residents of New Jersey receive a lot more from the insurance program than they pay into the system. New Jersey insurance policy holders, in general, receive 7.6 times as much money after flooding incidents as they pay in premiums. Communities like Sea Bright receive 13.1 times as much money.

"If it’s a good program, then the premiums that people pay in for the insurance would cover the payouts after storms, after disasters. But, that’s not the case for the NFIP as a whole, and it’s certainly not true for many of the New Jersey coastal municipalities," Andrews said. "The rest of the nation is subsidizing the flood insurance of those towns to a huge, huge extent."

In addition to those payouts, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers receives billions of dollars each year to engage in beach and dune development along America’s coasts, including in New Jersey.

Current policies mean that New Jersey and the federal government will be replacing those beaches every three to five years for the foreseeable future. "This is not a long-term solution for the Jersey shore," said Rob Young, director for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University in North Carolina. "It will require constant investment just to maintain the status quo. The amount of sand that we’re going to have to move and the amount of dollars that we’re going to have to spend is going to increase over time.”

The result is the federal government will continue to subsidize New Jersey’s multibillion-dollar shoreline industries through insurance guarantees and disaster relief even though storms will never stop visiting those shorelines. In many parts of the shoreline, there has been a post-Sandy building boom of secondary vacation homes joined by rising housing prices. Whether people would take the risk of building there if that risk wasn’t subsidized by the federal government, experts say, is unlikely. Plus, the political will for local communities to reject lucrative tax bases isn’t there.

For some on the shore, however, Christie’s rebuilding policies were exactly what they wanted and needed.

“We have a lot of people elevating, which is the right thing to do,” said Matt Doherty, the Democratic mayor of Belmar, which was particularly devastated during Sandy. Doherty said he was pleased with the governor’s response after the storm. Doherty agrees with Christie that widening beaches and building dunes are the way to go, and said just two full-time residents of his borough remain displaced. Doherty said that if Belmar had wider beaches before Sandy, the township wouldn’t have had as much of a problem.

Christie cited his disaster recovery efforts when he launched his underdog presidential race in late June from his childhood hometown of Livingston, New Jersey. “Unlike some people who offer themselves for president in 2016, you won’t have to wonder whether I can do it or not,” he said, invoking the “unprecedented natural disaster,” of Superstorm Sandy. At the time, more than half of all Republican primary voters said they couldn't imagine voting for Christie in 2016, according to an NBC-Wall Street Journal Poll. A Fox poll this week concluded Christie had support of only 3 percent of all GOP voters.

Another Sandy?

Many New Jersey homeowners struggled to receive aid after Superstorm Sandy. At the end of 2014, a total of 330 homes whose owners had applied for the primary grant system set up after Sandy -- known as the Reconstruction, Rehabilitation, Elevation and Mitigation program -- had been rebuilt, the Wall Street Journal reported. There were originally 15,000 applicants.

Many who were affected by the storm tell of a bureaucracy that was insufficient, opaque and slow. Christie’s poll numbers in his home state, astronomically high immediately after the storm, have fallen sharply since.

When Sandy flooded through Manuel and Adriana Gonzalez’s Union Beach home, it brought 8 feet of water into their first floor. The water and winds knocked their foundation around and destabilized their house to the point that when a demolition crane tapped a corner of their house, a whole portion collapsed like an avalanche.

The Gonzalezes have since rebuilt, and moved into a new home. The new house is on stilts, 16 feet higher than their old one, in the same spot. For the Gonzalezes, the years after Sandy were a swirl of fighting insurance and aid organizations for enough money to rebuild, filling out endless paperwork and fighting with what they perceived as predatory contractors and lumber salesmen.

Their neighborhood is dotted with houses waiting to be repaired, in the middle of rebuilding, or boarded up and abandoned.

Still, even with their new home lifted well above the federal flood line, the couple aren’t confident it’s enough to last another major storm like Sandy.

“I hope Sandy’s a 100-year storm,” Adriana Gonzalez said, referring to the estimated frequency of storms as big as Sandy. Because “if Sandy happens again, I’m gone.”

Experts critical of New Jersey’s shoreside development in the aftermath of Sandy recognize that Christie’s individual response looks a lot like what they might expect from any other coastal governor immediately after a storm. When a governor wakes up to thousands of displaced citizens, it’s difficult to react in any other way than to try to get them back home. Still, while Sandy was notable for its ferocity, it was not the first storm to hit Jersey. If nothing else, conversations about smarter development laws should start now, critics said.

Just one year before Sandy, Hurricane Irene brought its anger to the Jersey shore. Irene was a lightweight boxer compared to Sandy, but it still also destroyed Tezza’s pizzeria in Sea Bright. Tezza said he was grateful and supportive of Christie’s reaction to Sandy. But can Tezza or anyone else survive another major storm?

“How can people recover again?” he said. “It’s impossible. The force of nature, nobody stops that.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.