Climate Change Solutions: Architects Look To Slums As Models For Sustainable Living

In the barrios and favelas of South America, gondola lifts offer more than pretty views. They present an escape, however brief, from poverty, a link between slum life and the outside world.

In the past decade or so, cable car transit systems have become increasingly popular in Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela, especially in hillside slums where the only other way down is by narrow, zigzagging walkways and corridors. The soaring lifts carry commuters over the rooftops of the shanties, making the trek considerably easier and connecting residents with hospitals, train stations and commercial centers below.

In Rio de Janeiro, a six-station gondola lift that runs above the city’s Complexo do Alemão favela has turned a 1 1/2-hour hike to a nearby commuter rail station into a 16-minute aerial hop. In addition to a cable car system of its own, Medellín, Colombia, has an impressive, 1,200-foot covered escalator that slices through the sloped, densely populated community of Comuna Trece.

For designers in the age of sustainability, slums are a kind of proving ground for experiments in innovation and adaptation. Not only do new methods of local transit result in fewer barriers between the city’s poor and affluent neighborhoods, they're cleaner, more efficient and quieter than gas-guzzling buses -- all crucial features in the age of climate change.

As such, large, densely populated, impoverished neighborhoods are in many ways on the cutting edge. Innovation comes of necessity, not because it's trendy, and due to the likelihood the future will bring larger, more densely populated slums, an unusual realm of urban planning has begun to take shape -- one that looks at making slums sustainable, rather than simply blights to be eradicated.

As urban planners seek eco-friendly ways to house a projected 1 billion more slum residents worldwide in the next 35 years, they’re focusing on concepts like gondolas, rainwater catchment systems and vegetative walls that can be easily replicated -- in some cases across other economic zones. What works in the slums may be equally useful in high-rent neighborhoods, or in densely populated, middle-class high-hrise "towns" that are being built in Singapore.

One of the reasons such slums are useful to study is they are indicative of what a consumer society forced to grapple with declining resources could look like. And because the slums consume less than more affluent districts, residents' demands for transportation and water supply infrastructure are often easier to address.

“Slums are probably the best example of large numbers of people living without a car,” said Alfredo Brillembourg, founder of Urban-Think Tank, a contemporary architecture and design firm whose projects include a 2.1-kilometer-long cable car system in Caracas, Venezuela. “That’s why they’re so fascinating: The car-free city, the dream of every architect.”

For the first time in human history, more people live in urban environments than in rural ones, and there’s no indication that trend is letting up, particularly in the developing cities of Latin America, Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The 20th century saw cities build upward; the 21st century will see them spread out. Enter the megacity, an urban environment whose boundaries are ambiguous and whose sprawl fuses cities together like cells to create massive, seemingly endless metropolises.

The World Health Organization estimates by 2030, six of 10 people will live in cities, and by 2050, this proportion will increase to seven of 10. And as the world’s cities swell, so will their slums. Most rural migrants will end up living in informal squatter settlements where homes are built from whatever materials are at hand.

Urban renewal experts say while slums have obvious problems, including poor sanitation, disease and a lack of potable water, they provide cheap rent, close-knit communities, an escape from rural poverty and opportunities for employment. A growing sect of architects and urban designers like Brillembourg sees slums not as impediments to development but as places that should be embraced and improved.

“These areas need to be upgraded,” Brillembourg told International Business Times. But, he added, it would be a mistake to simply see slums "as problems, when in fact they’re the solution.”

What Brillembourg calls an “acupuncture” approach to development encompasses small-scale infrastructures like the gondolas of South America, which he said “can have a tremendous impact on an area.”

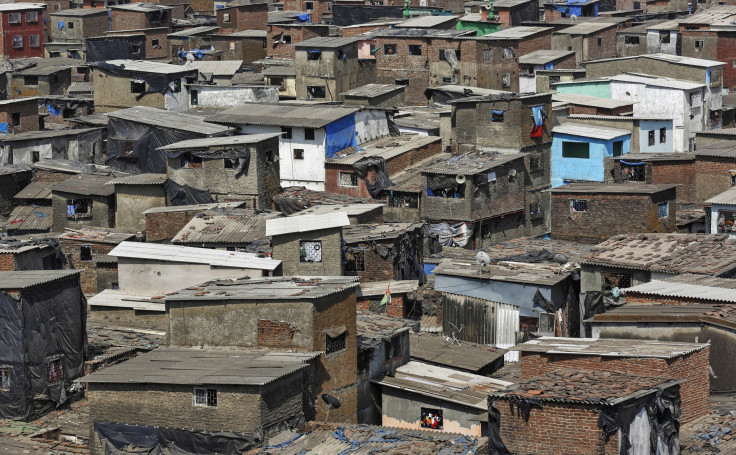

That includes Asia’s largest slum, Dharavi, in the heart of Mumbai, India’s financial capital. Set in a city where housing rents are among the highest in the world, Dharavi might as well be on a different planet, its rows of flat-roofed shanties connected by cramped, dirty lanes with open sewers are otherwise physically and economically cut off from the splendid towers of the city’s more affluent center. Penthouse apartments in Mumbai whose balconies overlook shanty homes made of corrugated aluminum and brick go for as much as $20 million USD; just down the road, Dharavi has only one lavatory for every 1,440 residents and the average annual salary is slightly more than $700 USD.

With some exceptions, major investment projects in Mumbai tend to serve the people whose standards of living are relatively high. The city recently unveiled an 8.8 kilometer monorail system as part of the government’s plan to improve its messy and overburdened transport infrastructure. While the monorail is a sleek and efficient addition to the city’s skyline, it passes right over the city’s slums, missing an opportunity to serve the people who could benefit the most from better public transit.

Dutch architect Neville Mars said during an Ink Conference talk in May local transport “becomes the backbone of ‘greenifying’ slums and cities such as Mumbai.”

In India, which has a preponderance of informal settlements, “a community-driven approach is required,” Mars said.

Such an approach involves adding amenities such as pedestrian skywalks and load-bearing “water walls” that collect and store rainwater and allow natural light to filter into dark apartments. The elevated walkways, according to Mars, can even be double-decker -- one level for pedestrians, the other for small vehicles. He also proposes turning rooftops into “green oases” to better regulate temperatures inside the apartments and to generally soften the physical environment.

Some approaches to improving slum infrastructure don’t require much effort. In Mumbai, a set of existing pipelines that stretch between two major slums have been adapted to include a footpath connector -- a sort of pedestrian freeway using an existing right-of-way. Simply adding a white line down the center would allow rickshaws to travel smoothly between the two slums.

“As planners, this is really all we can do: connect and patch,” Mars said. “On top of that, we hope that new social and public space can emerge.”

Mars’ ideas reflect a new model of urban renewal that eschews master plans for several, smaller, localized schemes. This blueprint for design is a departure from the large-scale development plans of the 19th- and 20th-centuries that focused heavily on big infrastructure such as skyscrapers and highways. The old paradigm involved leveling the old to accommodate the new.

A contemporary example of this top-down, heavy-handed approach to development is Singapore, which began to modernize in 1965, two years after the tiny Southeast Asian country gained independence from Britain and then Malaysia. Singapore started from the ground up, bulldozing slums to build high-rises, forever changing the country’s image and propelling it into an era of economic prosperity. Singapore is now one of the wealthiest nations on earth, per capita. It also is a rare case where slum-eradication worked, in part because the government had clear ideas of what would replace the poorer residential areas -- planned, sustainable high-rises. City-state leaders and developers also recognized early on the value of green development in a densely populated area with limited resources, and today the city-state is notable as much for its green approaches to renewal as for its considerable wealth.

While the incorporation of green roofs, green walls, waste and sewage recycling and rainwater catchment systems makes Singapore a model, it is in many ways unique, and the “tabula rasa” model for reviving a city -- wiping the landscape clean and building from scratch -- is largely irrelevant in the context of modern megacities, said Dana Cuff, a professor of architecture and director of City Lab at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“[The new] school of thought says informal settlements need architecture as infrastructure to rejuvenate them as economic generators,” Cuff told IBtimes. Simply tearing everything down is not a way “to make a vital, vibrant, decent city,” she said.

Cuff cited three components of sustainable development: social, economic and environmental. Investing in small-scale, local infrastructure, she argued, hits all three of these needs. A contemporary model of “radical incrementalism” is more appropriate for today’s sustainability-minded city, she said. Instead of razing slums, a city invests “a little bit at a time” in provincial projects that benefit whole neighborhoods and can be implemented elsewhere.

The concept of slum upgrading emerged from a period of extraordinary urban growth beginning in the mid-20th century. Proponents of the concept say devoting resources to a city’s poorest citizens is as vital to creating sustainable 21st century cities as is investment in real estate that will attract developers. Slum upgrading, according to Cities Alliance, an international organization of NGOs and government groups that have aligned to reduce urban poverty, is about providing city residents on all rungs of the income ladder basic amenities including clean water, footpaths, adequate drainage and sewage disposal.

The result is the same as what is at the core of any successful, democratic society: When a government provides its citizens with a clean, safe environment in which to live, and when freedom from hunger and disease are considered rights, not privileges, people find ways to make money and improve their own lives. Under Dharavi’s seedy surface are several booming leather, garment and pottery industries worth an estimated $650 million a year. When empower slum residents are empowered to work, urban renewal experts say, you allow these markets to grow and prosper.

Another way to make slums more sustainable is to grant residents a stake in their neighborhood, said Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto. When even the poorest residents of a city have legal claim to the land beneath their homes, they can turn their attention to updating their dwellings and starting businesses, de Soto said. Peru did this years ago, and it improved the situations of millions of impoverished families, he said.

In South Africa, creating vested interests in slum neighborhoods has included government-funded housing and water and sewage infrastructure, according to Cities Alliance. In parts of Latin America, where crime is often a major barrier to slum development, authorities greatly improved public safety by cracking down on criminals.

Then there are slums like Dharavi where environmental sustainability is simply a way of life. Britain's Prince Charles cited Dharavi as a place of “order and harmony” that can be a model for some British cities of how to live within one’s means. Residents of Dharavi recycle an estimated 80 percent of their plastic waste without formal collection facilities of any kind, and their dwellings are less energy-intensive than large-scale housing complexes.

“When you enter what looks from the outside like an immense mound of plastic and rubbish, you immediately come upon an intricate network of streets with miniature shops, houses and workshops, each one made out of any material that comes to hand,” the prince writes in his 2010 book “Harmony: A New Way of Looking at Our World.”

Still, portraying slum-dwellers as happy in their sustainable slums naturally sparks skepticism. Describing them as "harmonious" discounts the real hardships residents face on an almost daily basis.

“It’s possible to slightly over-romanticize the idea that these are places of great freedom, because you are obliged to fend for yourself,” Michael Sorkin, an architectural critic, author and professor in architecture at City College of New York, told IBTimes. “There’s definitely a place for large scale infrastructural intervention. Somehow the balance between the responsibility of the state and the empowerment of individuals has to be struck.”

Also, “the tool box is very limited,” Brillembourg said. The sustainable slum movement is short on resources because few developers and banks want to invest in something that’s not profitable, and as a result, much of the debate is academic. Aside from notable examples such as the gondolas of South America and incremental measures elsewhere, there are few physical examples of slum-upgrading models. Much of what is being proposed is expensive; even Urban-Think Tank’s gondola system in Caracas was postponed for more than a year and came in nearly 5 times over budget at a cost of $262 million.

Urban planners tend to speak about slum renewal in esoteric terms and cite theoretical models for lifting residents out of poverty. In fact, Mumbai -- which Mars cited as a perfect place to create sustainable slums -- continues to relocate slum dwellers into new, modern buildings in place of their current homes under the city’s nearly two-decade-old Dharavi Redevelopment Plan, and even the construction of those structures is far behind schedule.

The land on which Dharavi and other Mumbai slums sit is typically worth billions of dollars in development money, and developers are eager to raze them -- some have already succeeded in doing so -- to make way for high-rise apartment complexes and commercial centers that will bring in money. Activists and urban planners say the government aligns itself with whomever has the deepest pockets, as has happened on a notable scale in Lagos, Nigeria. “Instead of being seen as an issue, Mumbai’s slum problem is seen as a tool to cater to needs of the real estate,” Indian journalist Mahesh Vijapurkar wrote.

Brillembourg said most slum residents do not want an “IKEA” approach to shelter that focuses on high-rise apartment complexes tenants must go into debt to occupy. Many simply want out. But with more people destined for slums in the future, and resources expected to be in increasing demand, it's time to begin exploring how to sustain human occupation on the most basic level, he said. The trick will be finding out what works and what doesn't.

“There are many ways to skin the urban cat,” Sorkin added. “There’s no single model that fits all.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.