Communications During An Uprising: From Zello To Walkie-Talkies In Venezuela And Ukraine

A protester, bloodied by a blow from a policeman's club, needs to communicate to an organizer that the authorities have begun using force. A few blocks away, the organizer wipes tear gas from his eyes and wants to signal to his group to fall back. Rather than using shouts or even traditional walkie-talkies, both pull out their smartphones.

Welcome to modern civil disobedience: Rising up against your government? There's an app for that.

Of all the available group chat apps, Zello is credited with helping protesters across the globe organize and communicate, much as Twitter and Facebook did during the Arab Spring in 2010. Zello was the most popular app on the App Store and Google Play for several days in Ukraine before it began topping the charts in Venezuela. Reports from sources from NPR to Quartz extolled its developers' work to evade blocks put in place by Venezuela's state-run mobile service provider.

Zello works like a walkie-talkie, allowing users to broadcast voice messages to groups using their smartphone's data connection. It is used for many of the same tasks that walkie-talkies are, with a range as far as a phone’s data connection.

Launched in 2007, Zello is popular thanks to "the same qualities that have been popular with two-way radio for organizing people and events," Bill Moore, CEO of the Austin, Texas-based company, told International Business Times. "Participants don't need their hands or eyes. The information is in real time, it works with small or large groups. And voice carries much more information than text."

The media took notice of Zello’s popularity in uprisings throughout Venezuela and Ukraine, especially after reports surfaced that the Venezuelan government began blocking the app last month. Ninety percent of Venezuela’s Internet traffic is funneled through CANTV, a nationalized Internet and phone service.

Zello’s chief technology officer and founder, Alexey Gravrilov, told IBTimes that CANTV first removed access to Zello’s website from its servers, making the website and service inaccessible in Venezuela on Feb. 20. The following day, an updated version was submitted to Google and Apple that restored access for most users.

“Until now, the updated app allowed us to unblock access in Venezuela every time we discover it's blocked again,” Gravrilov said. “CANTV still keeps on trying to block it on a daily basis.”

Gravrilov advises those affected to use a VPN, or virtual private network, to avoid blocks like those instituted by CANTV in Venezuela. VPNs are encryption services that hide the way a user accesses the Internet, allowing them to circumvent blocks, download files and visit Web pages without the knowledge of outside interests.

In one of the most popular Venezuelan channels used by protestors, “Venezuela♥,” users were looking for information about the results of clashes with police, attempting to confirm reports of protest-related activities, and in general searching for news about what was going on in protests around the country.

The following Zello broadcasts were translated from Spanish:

“Here from Ecuador, we get no news from Venezuela, please inform, this is the only clean channel.”

“We need better information from the front at Miraflores [the presidential palace]. What is going on over there?”

“There have been no serious injuries in Isabelita. Five people to the hospital, but not serious.”

“Valencia... Any deaths? It looks terrible on TV, they are saying a child is dead, please confirm.” (Someone later told the user that there had been no deaths recently. The next day, two civilians and a police officer were dead.)

“Venezuela keeps on creeping up in the media, but all the info is manipulated,” complained one user. “They do not tell it like it is, there is no mention of tear gas or police brutality. Let's tell it like it is.”

Though Zello is particularly popular during early phases of protests, protesters often switch to other methods of communication once the situation intensifies. One Venezuelan protester who asked to be referred to only as Marlene told IBTimes that “not too many people” were continuing to use Zello on the front lines. Instead, she said, protesters had begun using encrypted chat apps and social media sites with privacy options that allow for greater protection against government entities.

“There are spies that listen to the conversation and everything that is going on,” she said. “The government is listening, and many don’t want to risk their freedom. This is why you can't talk much or say much in Zello. It is much better to use Facebook groups instead.”

For those who are worried about reprisal, such as Marlene, the open broadcast nature of Zello, where one user can broadcast a message to many others through “channels,” is also a weakness. While Zello allows users to create closed channels that require approval before people can join, the confusion and mass numbers involved with protests means that regulating those channels is difficult.

Moore told IBTimes that his company has also “offered free Zello@Work to protest organizations because it is both fully encrypted and centrally managed.” Unlike many other popular messaging apps, Zello is completely anonymous because it does not require a user to confirm his or her account with a phone number or email address.

Moore says that Zello’s newfound popularity in protests has spurred the company to begin work on encryption for the free version for consumers. “Twitter and Facebook did the same after their early use by organizers.”

Ukraine’s Shift From Walkie-Talkie Apps To The Real Thing

Protesters in Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square, used Zello during the initial days of the Ukrainian uprising. As the protests escalated into violence, organizers switched to real walkie-talkies for most communications. Out of the 50 or so groups still camped out in the Maidan, all still have at least one or two people designated to use Zello.

Petro, a 28-year-old from Ternopil, says his group used one institutional account on Zello for updates on security, alerts, whether roads were open or closed, and the arrival of supplies, including food and medicine. It was important during the worst days of clashes but now is mostly idle. The groups also used personal Zello accounts for chatting and having private communications.

Petro mans one of the main entrances to the Maidan, off of the barricades on the slope of Institutska Street, by the Ukraina Hotel, a strategic location during the uprising. Petro said that groups switched to real walkie-talkies because reception and sound quality was poor on Zello.

Marian, age 25, from Lviv, Ukraine, used Zello regularly with his group, 30 or 40 people from Galits'ka Diviz'ya Sotnya “Leva,” a nationalist self-defense brigade from Western Ukraine. Marian used the app to communicate with other group members. Though they have since switched to walkie-talkies, he said the group began using Zello after it was advertised on Maidan.SOS, a network coordinating the rebellion effort, in December 2013.

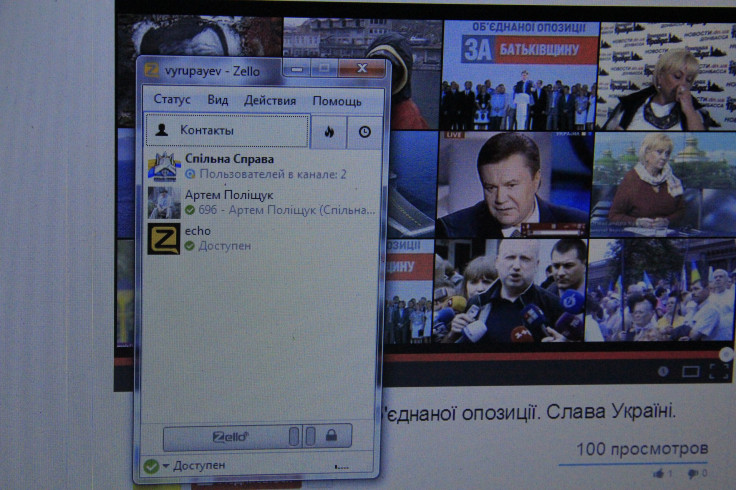

One group that still uses Zello regularly is the information center of Spylno Sprava, a nonpolitical group at the Maidan. The Zello point person is Artem Polyshiuk, who estimates that some 30,000 people used the app during the Maidan rebellion. He said there were a number of channels, three of which were dedicated to AutoMaidan, a group of motorists who defended the Maidan and patrolled the periphery during the clashes with soldiers.

According to Anna Pyatetska, a 21-year-old from Kiev, apps like Zello were used because smartphones were more readily available than standard walkie-talkies. Zello was used to organize protests as well as spread news about what was happening.

“With time, [protest leaders] managed to get almost everything we needed, so people who really needed to communicate with each other got walkie talkies,” Pyatetska said.

The men manning the roadblocks and other activists used a number of communication methods, including walkie-talkies, Zello, chat apps like Viber and WhatsApp, and standard phone calls and texts during the crisis.

“Of course, a lot of info was generated through Facebook,” Pyatetska said. “Even lives were saved, thanks to posts from injured people who informed where they were and what was happening.”

She said the groups now communicate mostly about their location and where they are headed. That way, if someone goes missing, “at least they know where they can start their search.” Finding lost people, especially in Crimea, is now a priority for volunteers like Pyatetska, who recently returned from studying in Switzerland and had hoped that joining the European Union would help the Ukrainian economy grow, as it did Poland’s when that country joined in 1996. But for now, communicating with her peers is the most important thing on her mind.

"We have an organization called Crimea.SOS, and they are basically trying to protect people, citizens of Crimea, and finding journalists, or activists who are missing because of the actions of the Russian army," she said.

Additional reporting by Avedis Hadjian from Kiev and Patricia Rey Mallén from Mexico City.

Follow Reporter Thomas Halleck on Twitter

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.