Deadly MRSA Superbug Killed By 1000-Year-Old Anglo-Saxon Remedy

A 1,000-year-old Anglo-Saxon remedy for eye infections has been found to be effective against antibiotic-resistant superbugs, researchers from the University of Nottingham said on Monday. The scientists recreated a 9th Century remedy to treat styes.

The age-old remedy called for "cropleek and garlic, of both equal quantities, pound them well together … take wine and bullocks gall, mix with the leek … let it stand nine days in the brass vessel," according to the New Scientist.

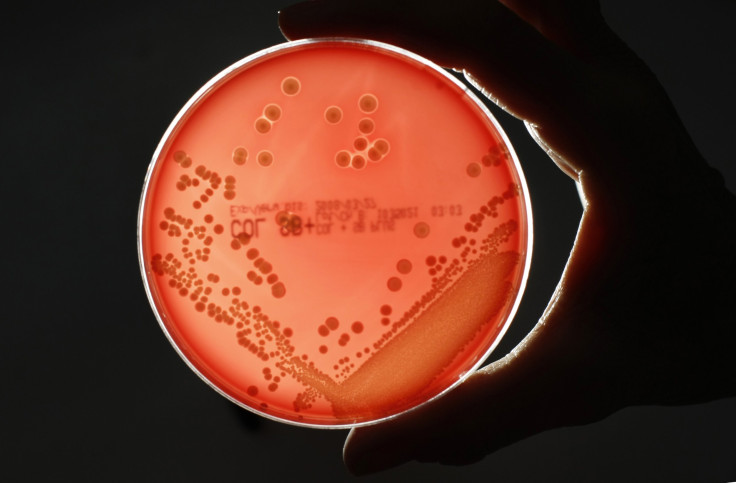

Some of the ingredients, such as copper from the brass vessel, have antimicrobial properties, but the scientists were not sure if the recipe would be effective against infection. They tested it on tissue samples from mice infected with the MRSA superbug, an antibiotic-resistant strain of Staph, which the U.S. National Institute of Health says has “evolved from a controllable nuisance into a serious public health concern.”

The researchers had the idea during an academic meeting to discuss infectious diseases where Anglo-Saxon expert Christina Lee told microbiologists about Bald’s Leechbook -- an Anglo-Saxon medical text that contained remedies for various ailments. She translated the text of the recipe, which proved to be an “incredibly potent” antibiotic, according to lead researcher Freya Harrison.

The concoction killed up to 90 percent of MRSA bacteria in infected mice.

“I still can’t quite believe how well this one thousand year old antibiotic actually seems to be working, when we got the first results we were just utterly dumbfounded. We did not see this coming at all,” Harrison told The Independent.

The ingredients were found to have little effect individually, and the researchers speculate that they react in some unknown way to become more potent when brought together.

Lee said the remedy is just one of many potentially useful infection treatments contained in ancient texts. “Modern research into disease can benefit from past responses and knowledge, which is largely contained in non-scientific writings. But the potential of these texts to contribute to addressing the challenges cannot be understood without the combined expertise of both the arts and science,” she said in a Monday press release.

The team is due to present its findings at the annual conference of Society for General Microbiology in Birmingham on Wednesday, and the results of the study will be shortly submitted to the journal Nature.

"This truly cross-disciplinary project explores a new approach to modern health care problems by testing whether medieval remedies contain ingredients which kill bacteria or interfere with their ability to cause infection," Harrison said in the statement.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that at least 2 million people are infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria every year, and at least 23,000 people die from these infections.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.