Does Prince William’s Visit to China Highlight The UK’s Popularity Or Its Downgraded International Status?

SHANGHAI -- On the second full day of his tour of China -- the highest-level visit by a member of Britain’s royal family since 1986 -- Prince William, the Duke of Cambridge, attended an exhibition of British creativity, met students who had returned from the U.K., played football with school children, and attended the opening of the film "Paddington" at Shanghai’s film museum, as part of attempts to project a youthful image and engage with China in the creative industries.

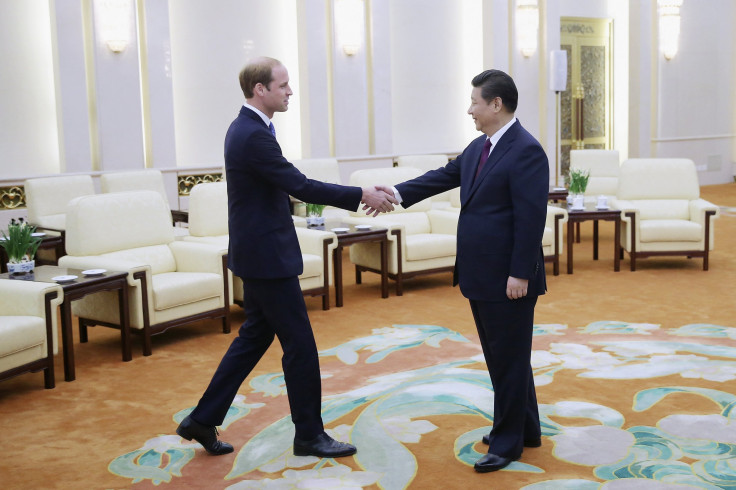

The visit has been seen by both British and Chinese analysts as a sign that relations between the two countries are now back on track, following tensions after a meeting between British Prime Minister David Cameron and the Dalai Lama in 2012, which infuriated Beijing. The prince’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping on Monday appeared to be confirmation of this, with the two holding a cordial discussion that covered topics including soccer. The 32-year-old prince has attracted much interest in China since his childhood, not least because of the popularity of his late mother, Diana, Princess of Wales -- who one Shanghai media commentator this week described as a “goddess” -- in the country in the 1980s and 1990s.

The image of the young prince and his brother Harry at her funeral in 1997 touched many in China, while his marriage to Kate Middleton, now Duchess of Cambridge, in 2011, also aroused some excitement: the traditional pomp and circumstance appealed to those members of China’s new rich and the middle class who have shown a growing interest in European aristocracy and the luxury lifestyle that goes with it, while the fact that the young prince made his own choice to marry a ‘commoner’ also impressed many young people in a country where members of the young generation still frequently face pressure to marry to suit their parents’ wishes. The subsequent popularity of TV shows such as "Downton Abbey" and the BBC’s "Sherlock" on China’s video-streaming websites has only added to interest in things traditional and British.

Yet with China’s leadership in the midst of a campaign to root out Western influence from areas such as academia, and regular warnings in state media about the threat of "hostile foreign forces," official media coverage of the visit has been relatively muted. The prince’s meeting with the president was reported on television on Monday, but most major Chinese-language newspapers did not feature it on their front pages on Tuesday, preferring to focus on preparations for the opening of the annual session of China’s legislature later this week.

The Global Times, a popular tabloid published by the official People’s Daily newspaper group, reported the story on page two, but put the focus on the British press’ excitement that the prince had been granted a meeting with Xi, which it said had only been agreed upon a few weeks earlier. Most Shanghai newspapers, meanwhile, relegated coverage of the visit to their world news sections in the middle pages, and many headlines focused on the invitation delivered by the prince to Xi to visit the U.K. later this year.

Nevertheless, some coverage did betray a mood of excitement. Several newspapers highlighted the fact that Xi, a soccer fan, had discussed with the prince what China could learn from the U.K. to improve its national team’s performance. The Shanghai Morning Post, meanwhile, emphasized that it was the prince’s personal charm and influence that drew a large crowd to the opening of Britain’s “Great Festival of Creativity” in Shanghai, including China’s two richest men, Jack Ma, founder of e-commerce giant Alibaba, and real estate-to-movie theater tycoon Wang Jianlin.

The paper also highlighted the excitement of “fans” who, it said, screamed “William We Love you” when the prince arrived at the venue -- and noted that many had been attracted by a message on the British embassy’s social media account entitled, "How to bump into Prince William," which outlined his schedule in China. Some of the crowd, the paper reported, had travelled hundreds of miles from Henan province to see him. The paper also interviewed a local man who it described as a “devotee” of the royal family: he told the paper proudly that he had been in the U.K. when the prince’s son, George, was born in 2013, and had waited outside the hospital for news of his birth.

There were also positive reports of the prince’s commitment to charitable causes, which the Shanghai Morning Post said he had inherited from his mother. It highlighted his planned trip, on Wednesday, to the southwestern province of Yunnan to visit an elephant sanctuary, as part of his campaign against the ivory trade. Shanghai TV news also took a sympathetic approach to the prince’s visit, depicting him in cartoon form with a gold crown on his head, and describing his visit as a continuation of the one by his “grandma” in 1986.

Yet, Chinese media also emphasized that much has changed in the relationship between Britain and China over the past three decades, with many reports highlighting Britain’s desire, and need, for Chinese investment. Accompanying the prince to Yunnan will be Yuan Yafei, head of the Sanpower Group, which last year bought House of Fraser, one of Britain’s oldest department store chains.

“Prince William really wants to know what kind of Chinese person bought such a famous British department store,” Yuan told the Shanghai Morning Post, adding that he was considering further investment in the U.K. this year.

And while the prince’s visit has seen the signing of other agreements, including new direct flights by China’s Hainan Airlines to the British city of Birmingham, and a plan to promote exchanges by film students, some British observers say the country’s diplomacy is still too focused on high-profile visits and promoting the interests of big business.

“Concentrating on these symbolic events is a very old fashioned approach,” Kerry Brown, head of the China Studies Centre at Sydney University and a former British diplomat in Beijing, told International Business Times in a telephone interview. Brown’s new book, "What’s wrong with diplomacy," calls for British embassies and consulates to become more transparent, to share their expertise more widely, and to bring in non-career diplomats to help them engage more with a wider cross-section of society in countries like China.

“Britain and China have had very good people to people relations,” Brown said, “but this is in spite of, not because of the diplomats and politicians. Diplomacy should be promoting more serious intellectual cooperation, in fields like medical research and engineering. It’s still too exclusive -- just as any royal visit is, by definition -- at a time when China is no longer a minority interest in Britain.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.