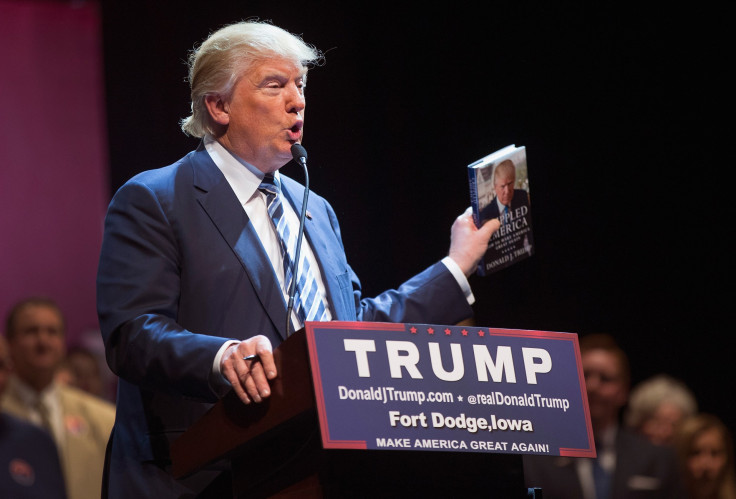

Donald Trump Explained How To Dominate The Media In 1987: 'I Play To People’s Fantasies'

America is now in its sixth straight month of Trumpmania. The mogul-turned-GOP front-runner is a man for all seasons, and there has not been a week that’s gone by without Trump dominating headlines, cable news segments and Twitter feeds. Every time his critics declare he’s gone too far, another poll drops showing him bursting ahead of the competition. Diagnosing “peak Trump” has become a fool’s game.

Some recent examples: After journalists lampooned him for play-acting rival Ben Carson’s claim to have stabbed a childhood friend, Trump shot ahead of Carson by 17 points. Following the Nov. 13 terror attacks in Paris, Trump’s anti-immigration crusade, once seen as a major liability, has appeared to boost his numbers even higher.

Now, with his call to ban all Muslims from entering the U.S. -- whether they're citizens or not -- Trump has once again baited the media into dedicating another week of coverage to another outrageous claim. Washington Post's op-ed page produced a litany of Trump takedowns; BuzzFeed put out an internal memo calling Trump a "mendacious racist" who needed to be called out; cable news, particularly CNN, spent another day down the Trump wormhole.

The common wisdom is that Trump is winging it, a raging bull in the china shop that is American democracy. This assessment, however, is wildly at odds with one key fact: Trump wrote very openly and specifically about pursuing this strategy in his bestselling 1987 book, "The Art of The Deal."

As his how-to manual shows, there is little that’s improvised in Trump’s approach toward dominating the press. The only thing that’s changed is he’s moved from business to politics.

Trump on Trump

“One thing I’ve learned about the press is they’re always hungry for a good story, and the more sensational, the better,” he writes on page 56. “It’s in the nature of the job, and I understand that. The point is that if you are a little different, or a little outrageous, or if you do things that are bold or controversial, the press is going to write about you.”

“I don’t mind controversy, and my deals tend to be somewhat ambitious,” he added. “The result is that the press has always wanted to write about me.”

He anticipated that the media wouldn’t get too hung up on whether a plan -- back then a building development, nowadays, a policy -- was workable. They’d still dedicate reams of paper, bundles of airtime, to chattering about it. “Most reporters, I find, have very little interest in exploring the substance of a detailed proposal for a development. They look instead for the sensational angle,” he wrote. “That may have worked to my advantage.”

Though he identified as a Democrat at the time, Trump echoed the same lines he’s employed since running for the GOP nomination, like when he blasted Fox News and Megyn Kelly for treating him “unfairly” during the first presidential debate.

“[W]hen people treat me badly or unfairly or try to take advantage of me, my general attitude, all my life, has been to fight back very hard,” he wrote. After Kelly tore into him during the debate this summer, Trump launched a campaign against Fox News that eventually drew in his friend, Fox boss Roger Ailes.

“The risk is that you’ll make a bad situation worse, and I certainly don’t recommend this approach to everyone. But my experience is that if you’re fighting for something you believe in -- even if it means alienating some people along the way -- things usually work out for the best in the end.” Trump settled the Fox feud this summer by appearing on the network for a fawning interview with Sean Hannity.

He even presaged his penchant for calling into morning shows on Fox, CNN and MSNBC: “You need to generate interest, and you need to create excitement. One way is to hire PR people and pay them a lot of money to sell whatever you’ve got. But to me, that’s like hiring outside consultants to study a market. It’s never as good as doing it yourself.”

‘Truthful Hyperbole’

Trump gets more honest about his approach the further along you read. By the end of his section on manipulating the media, he ends up coining a phrase that could have made George Orwell blush.

“The final key to the way I promote is bravado. I play to people’s fantasies. People may not always think big themselves, but they can still get very excited by those who do,” he writes on page 58. “That’s why a little hyperbole never hurts. People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular.”

“I call it truthful hyperbole. It’s an innocent form of exaggeration -- and a very effective form of promotion,” he added.

Trump, who may or may not admit he's not a scientist, has the research on his side here. Decades of studies back up his claim that people are drawn to shameless narcissism, be it in the realm of politics, business, war or show business.

The Harvard Business Review parsed a recent study by Robert B. Kaiser and Professor Bartholomew Craig -- it could have been written about Trump, from his history-making contribution to cable TV ratings to his sensational Twitter presence.

“[N]arcissists’ desire to make a great initial impression enables them to disguise their arrogance as confidence, which they often achieve through humor and by being entertaining or eccentric,” HBR said. “Unsurprisingly, narcissists perform well on interviews and they are excellent social networkers – you can even spot them by their social media activity.”

I told you @TIME Magazine would never pick me as person of the year despite being the big favorite They picked person who is ruining Germany

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 9, 2015Interestingly, while discussing the nature of “truthful hyperbole," Trump mentioned another onetime, long-shot presidential candidate running as an outsider: the Republican Party’s beatified hero, Ronald Reagan, who was president back when “Art of the Deal” was published.

“Ronald Reagan is another example. He is so smooth and so effective a performer that he completely won over the American people,” Trump wrote. “Only now, nearly seven years later, are people beginning to question whether there's anything beneath that smile.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.