Drugs And Money In The Sahara: How The Global Cocaine Trade Is Funding North African Jihad

Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the notorious one-eyed military commander of an al Qaeda-linked terrorist group in North Africa, once earned himself the nickname Mr. Marlboro -- but it wasn’t because of his rugged good looks or cowboy attitude. Belmokhtar, who has been sought by U.S. authorities for years, earned the moniker for his major role in trafficking smuggled cigarettes across the Sahara desert. And like many jihadi leaders of armed groups in the region, he helped funnel the profits toward his group’s activities.

That was more than a decade ago, when he was still working for al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), but running a team of jihadi militants in the middle of the desert hasn’t gotten any cheaper.

“To maintain these groups you need millions of dollars, and the money has to come from somewhere,” said Pierre Lapaque, regional representative for West Africa of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. To feed that need, he explained, many of the jihadist groups that have blossomed in the lawless desert regions of Niger, Mali and Algeria are getting in on something more lucrative than smuggled cigarettes: They are making money from cocaine.

AQIM and splinter groups such as Ansar Dine or the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa have moved beyond making money from kidnapping ransoms. These days, the bulk of their funds comes from across the Atlantic Ocean.

“It comes from Colombia, Peru and Bolivia,” Lapaque said. “It is coming from trafficking.”

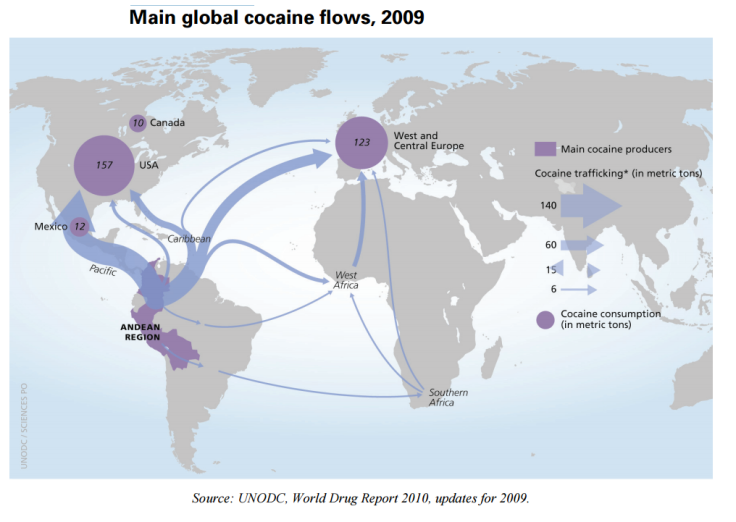

According to his estimates, between 30 metric tons and 40 metric tons of cocaine come through West Africa every year en route to booming markets in Europe. While a great deal of the profits go to the South American drug cartels, the African traffickers, often from local tribal groups, are getting a big cut, too. Jihadist militias that have blossomed in the region’s chaos in recent years have managed to get a piece of the profits, thanks to their control of ancient trade routes through the Sahara.

Air Cocaine

For a little over a decade, drug cartels in South America have been sending their products through West Africa to reach eager customers in Europe. Generally, the drugs cross the Atlantic over the infamous “Highway 10” -- a route along the 10th parallel that is the shortest distance between the two continents -- by ship or air.

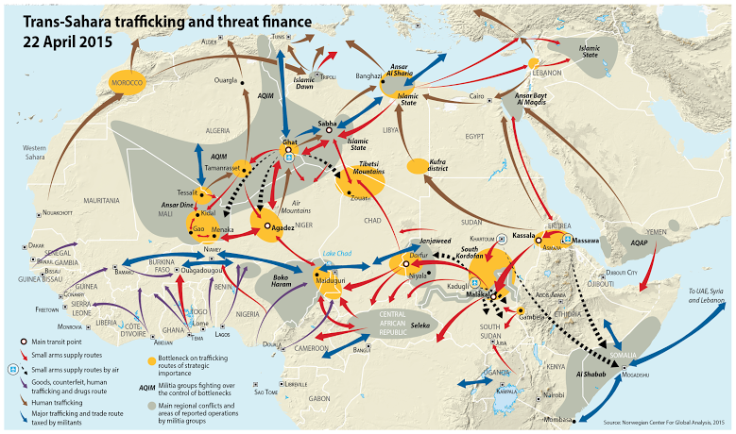

From there, the path to Europe goes north through the Sahara along routes once trod by camel caravans, which for centuries carried goods both legal and illegal. For generations, tribal groups such as the Tuareg and Tebu have controlled these networks. Though their convoys today are made of 4x4s with global positioning systems instead of camels, they are still the experts in trafficking anything from weapons to cigarettes.

And Mali, which has been embroiled in conflict for years, is an easy route to take. The latest period of instability began in 2012, when rebel groups seeking independence and autonomy for the country’s northern region began attacking government troops. And despite an intervention from French troops in 2013, extremist jihadist groups continued to thrive in the chaos, with new organizations continuing to reveal themselves through violent attacks against troops from Mali, France and the United Nations.

At the same time, authorities began seizing larger and larger amounts of cocaine in the area. On one occasion in 2009, authorities recovered north of the Malian city of Gao the fuselage of a Boeing 727 thought to have been transporting up to 10 tons of cocaine from South America, in an incident now known as “Air Cocaine.” By 2014, there had been a major increase in cocaine seizures in Algeria, where it was coming through West and Central Africa, according to the 2014 World Drug Report.

It didn’t take much for analysts to make a connection between these revenue streams and the rise of jihadists, but the relationship isn’t a direct one.

“Most of the trafficking and informal trading is by individual clans of many different tribes, but primarily the Tuaregs and the Toubou people,” said Christian Nellemann, expert on threat finance and director of the Norwegian Center for Global Analysis. Generally, for smugglers, the product doesn’t matter as much as the fee. A person could be smuggling cigarettes one day and switch to drugs or weapons the next. And while jihadists aren’t driving the goods themselves, the drivers still have to go through their territory, and that’s where the militants make their money.

“If insurgent or terrorist groups profit from illicit trade, they are more likely do so by taxing the movement of goods through territory they control, rather than being involved in the movement of the goods themselves,” said a 2014 report by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime.

The model has worked well. It helps the groups avoid any direct connection to the trafficking, since the transporters themselves take the fall if they do get caught. For instance, Malian authorities eventually arrested a French pilot and a local businessman for their connection to the “Air Cocaine” incident, even though many suspect that jihadi groups profited from the loot.

Groups such as AQIM earn about half the profits generated from drug trafficking, and those can take the form of direct cash payments or weapons, ammunition, vehicles or other equipment, according to a report from Francesco Strazzari, associate professor of international relations at Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies.

It’s no small business. Cocaine trafficking in West Africa generates about $800 million every year, according to the United Nations. And that’s before it sells for billions in street value after it reaches Europe.

And though it’s been very profitable, jihadist groups in the Sahara have recently discovered yet another way to use the same smuggling routes to trade something even more lucrative.

The Emerging Migrant Market

In 2010, roughly 4,500 people were picked up by Italian authorities trying to cross from Libya into Europe via the Mediterranean Sea. By 2014, this number had reached 170,000, according to Italian government data cited by the Associated Press. Though the largest part of this group is refugees fleeing war in Syria, more than 50,000 came from sub-Saharan Africa -- each of them paying thousands of dollars to make the journey through the same ancient trade routes across the Sahara to Libya before making the trip to Europe.

With rising numbers of emigrants making the trade more profitable than ever -- more than 35,000 people have already made the same crossing in the first four months of 2015 -- it’s not surprising that armed jihadist groups are getting in on it.

“This lucrative business has caused a dramatic increase in the number of groups involved in trafficking,” said a recent update from the Global Initiative, which explains how terrorists are getting more involved. After Libya’s fragmentation, the chaotic region has become even more of a safe haven for armed groups to operate relatively freely.

“There seems to be no lack of opportunity for these groups to make alliances with, profit from or to tax the smuggling and trafficking trades perpetuated by the proliferating number of armed groups and criminal networks in the region,” the report said.

And for some of those groups, funding jihad through smuggling is nothing new. Al-Mourabitoun, one of many emerging armed groups in the region, which made headlines after a series of attacks on U.N. peacekeepers, happens to be led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar -- none other than Mr. Marlboro himself.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.