Fed Regulators Accuse Murray Energy Of Trying To Silence Whistleblowers, Creating 'Atmosphere Of Intimidation' At 5 West Virginia Coal Mines

A few hours before their afternoon shift at the Marshall County Mine last spring, hundreds of coal miners were summoned to a mandatory meeting with their new boss, Bob Murray, CEO of Murray Energy Corp. At a training facility in Moundsville, West Virginia, the chief executive of the nation's No. 1 underground coal producer sported his signature sweater vest and struck a confrontational tone.

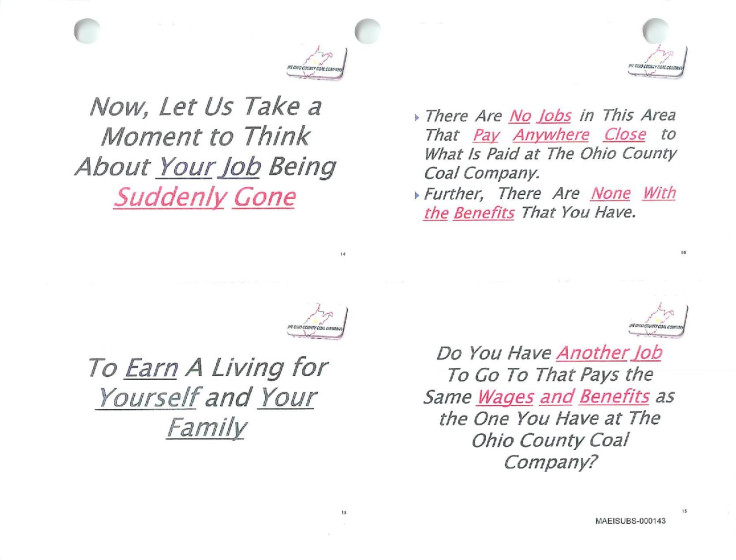

"Now, let us take a moment to think about your job being suddenly gone," read one of the slides in Murray's accompanying PowerPoint presentation.

The CEO told the gathering that the coal industry is under siege and said workers should be grateful for their jobs. Another section of his presentation was more pointed: The company, which has come under fire for its safety record, is committed to working together, but miners are filing too many anonymous safety complaints with the federal government. Murray gave similar speeches to workers on the other two shifts at the mine that day in late April 2014 -- and eventually, at four other West Virginia mines.

Now, more than a year later, federal regulators are accusing Murray Energy of attempting to silence mine safety whistleblowers. The U.S. Labor Department alleges that the company interfered with miners' rights under the Mine Safety and Health Act to lodge confidential safety reports with federal regulators. In a complaint, regulators say Murray Energy chided 3,500 workers for making too many confidential safety complaints to regulators and -- at one of the mines -- threatened to retaliate by closing down operations.

Alan Bailey attended one of Bob Murray's meetings. "They want you to bring the complaints to them, and there's times that we have," says the 58-year-old miner, who has spent eight years on the safety committee at the Marshall County Mine. "We told them and told them, and they didn't do anything about it."

'An Atmosphere Of Intimidation'

According to documents obtained by International Business Times, lawyers with the Labor Department criticized Murray in October for personally creating "an atmosphere of intimidation" at five West Virginia mines. Regulators expounded on their accusations in a post-hearing brief that stems from a lawsuit they filed against the company in July.

Murray Energy disputes the Labor Department's claims. "These allegations are blatantly false," says spokesman Gary Broadbent. "We will continue to vigorously defend against these frivolous claims."

The case now stands before an administrative law judge at the Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission in Washington, the federal court system for mine safety violations. If found responsible for interfering with miners' rights, the company could owe $120,000 in penalties sought by regulators. In addition to fines, CEO Bob Murray could be forced to personally read notices that inform workers of their whistleblowing rights. IBT obtained copies of the complaint and subsequent court filings through a Freedom of Information Act request.

The accusations bring renewed focus to the safety practices of the privately held coal giant. Murray Energy operates 13 coal mines in the U.S., many of which have drawn regulatory scrutiny. All five of the West Virginia mines included in the complaint have rates of "significant and substantial" health and safety violations greater than the national average. In March of this year, a worker died from a roof collapse at the Marshall County Mine in a tragedy that regulators blamed on the lack of a proper safety protocol. And in 2007, six workers died in the collapse of a Murray-owned mine in Utah, one of the deadliest U.S. mining disasters of the last two decades. Federal inspectors said the operator's "flawed mine design" caused the accident.

The company says it makes safety a priority.

"Mr. Murray is a leader in the United States coal industry and a champion of mine safety," Broadbent says. "Indeed, he frequently tells our employees that 'There is no pound of coal worth getting hurt over,' and no topic is discussed until all safety issues are fully addressed."

'A Rash Of Complaints'

According to the Labor Department, Murray Energy's frustrations with the number of anonymous safety complaints at the mines began shortly after the company purchased them from Consol Energy in December 2013. The operations, all in northern West Virginia, are known today as the Ohio County Mine, Marshall County Mine, Monongalia County Mine, Marion County Mine and Harrison County Mine. Workers there are represented by the United Mine Workers of America. Most of Murray Energy's other mines are non-union.

In April 2014, according to court documents, Murray Energy sent letters to the president of the union and more than 30 Murray executives in addition to local union presidents, mine committee members and safety committee members at the five mines. In the messages, Bob Murray and mine superintendents complained that the mines were seeing too many confidential safety complaints -- known in the industry as 103(g) reports.

That section of federal mining safety law gives miners the right to request that federal inspectors conduct a special inspection of their worksite if they have "reasonable grounds to believe that a violation" of mandatory health or safety standards exists or if "an imminent danger" exists.

Workers make these complaints confidentially -- and directly -- to the nation's chief mining safety agency, the Mine Safety and Health Administration. The agency, in turn, does not disclose the names of the miners who filed the complaints to the mine operator.

Inspections triggered by the confidential complaints at Murray's mines turned up a number of violations, according to regulators. Among other hazards, they found extensive accumulations of coal and coal dust along conveyor belts, inadequately supported roofs, inadequate ventilation and inoperative emergency communication systems.

But in letters to corporate managers and union officials, Murray Energy blamed the complaints on vengeful workers. "What is occurring, and we are seeing it, is that disgruntled employees are striking back at the company for reasons other than safety," Bob Murray wrote in the letter to the president of the union.

Over the next few months, Murray personally traveled to each of the mines to preside over mandatory meetings with hundreds of workers at a time. A hallmark of the executive's hands-on management style, the quarterly mass meetings are known as "awareness meetings." Murray has said the gatherings remind workers "why they are here and keep them focused."

During Murray's speeches, the company showed nearly identical PowerPoint presentations to workers. Each of them brought attention to the industry's struggles and urged workers to reflect on the lack of well-paid jobs in the areas surrounding the mines; one of the slides slams the Obama administration for "destroying coal"; another notes that only the "lowest coal in any sourcing region will survive in the current coal marketplace"; another one, at the Marion County Mine, criticizes workers' productivity, saying "employees are not hustling."

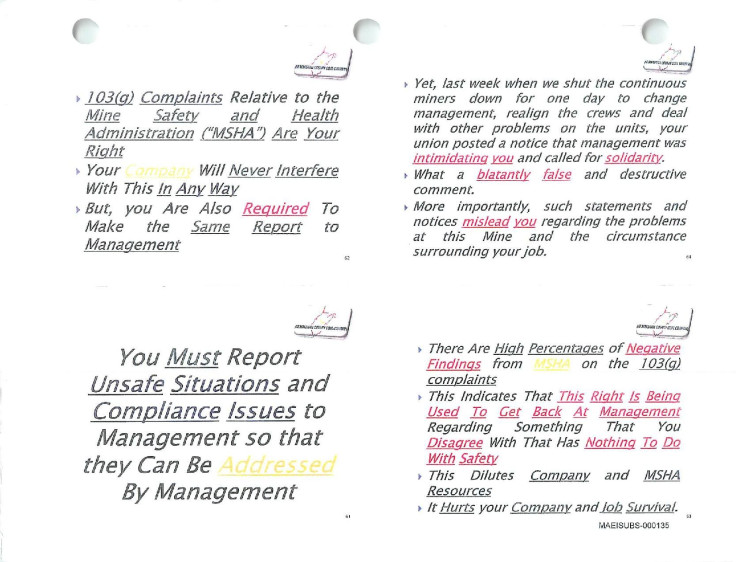

Each of the presentations also gave instructions about making confidential complaints: Workers were told they were free to make so-called 103(g) complaints to the government, but that they were required to notify management each time they did so.

"You must report unsafe situations and compliance issues to management so that they can be addressed by management," the slide reads. "103(g) complaints relative to the Mine Safety and Health Administration ('MSHA') are your right. Your company will never interfere with this in any way. But you are also required to make the same report to management."

At the Marshall County Mine, a worker made a covert audio recording of Bob Murray's speech. While safety complaints filed by miners did, in fact, reveal numerous violations, Murray suggested otherwise.

"This all hurts you," Murray said, according to the recording. "When we're fighting inside and we get shut down because of a 103(g) complaint because we're mad at somebody in management, that just hurts you. It just hurts you. If there was an unsafe condition, and we got shut down, I don't have a complaint. But what's happening is that MSHA is finding negative findings. ... MSHA's fed up with it too."

He added, "And if you want to fight inside, let me tell you, I'll go on to a better coal mine and we'll close this one."

Alan Bailey, who is soon to retire after recently being diagnosed with black lung disease, recalls Murray making those remarks. He says such an alleged threat would have scared him during his younger days. But "as a person who has been underground 18 years," he says, "I've heard that stuff so many times."

In addition to challenging the recording's reliability in a post-hearing brief, company lawyers rejected the government's argument that Murray's comments constituted a threat. Any statements about job security were not "tied directly to the reporting of safety issues" but "rather to the generalized challenges facing the coal industry and the specific challenges facing each of the local subsidiaries," the company says.

In that same brief, the company says the instructions that Murray gave workers about filing complaints at the five mines were not "tantamount to promulgating a new work rule." In order to implement new safety rules, Murray Energy lawyers argue, the company must follow the official process prescribed in its labor contract. Even if implemented such a rule, it does not meet the standard for constituting a violation of miners' rights, the company says. The company says the presentations indicated the company "would never interfere" with the right to file confidential complaints.

A spokesman for the United Mine Workers of America says the company has not given workers the same instructions about filing safety complaints with management since the lawsuit was filed in July.

A Dangerous Industry

Despite major safety improvements over the years, mining remains one of the most dangerous and deadly industries for American workers.

Confidential complaints play an integral role in mining safety, says Stephen Sanders, director of the Appalachian Citizens' Law Center, a nonprofit that represents coal miners on issues of black lung disease and workplace safety.

"This seems to me really chilling. What the law says is miners have the right to make these complaints," says Sanders. "It may seem reasonable to say 'go to managers first,' but that can be very intimidating for miners."

For instance, in the lead-up to the disaster at Massey Energy's Upper Big Branch Mine in 2010 -- an explosion that killed 29 miners -- regulators found that workers were afraid to raise safety problems with their managers or with the government.

"Witness testimony revealed that miners were intimidated by UBB management and were told that raising safety concerns would jeopardize their jobs," concluded an investigative report from the Mine Safety and Health Administration. "As a result, no safety or health complaints and no whistleblower disclosures were made to MSHA from miners working in the UBB mine in the approximately four years preceding the explosion."

Safety regulators later fined Massey nearly $11 million. Now the company's former CEO, Don Blankenship, is on trial on criminal charges.

Regulators found that Massey Energy's corporate culture encouraged rampant disregard for safety. No such evidence exists at Murray Energy.

But as labor attorney Tony Oppegard points out, many of the violations that inspectors say they found at Murray's mines are just as serious -- and preventable -- as some of those at Upper Big Branch.

From December 2013 to July 2014, the month of Murray's last "awareness meeting" in which he allegedly told miners to come to management with safety issues, inspectors issued 70 citations and orders prompted by confidential complaints.

"The types of citations that were issued are chronic violations -- failure to clean the belt line, loose accumulations of coal and coal dust," says Oppegard, who advised the head of the Mine Safety and Health Administration from 1998 to 2001 and later served as the chief mine safety prosecutor for the state of Kentucky. "Those are fire hazards. All it indicates is that the mine operator is lazy or unwilling to invest enough money to have sufficient number of people to keep the mine clean."

Coal dust can be deadly. Long-term inhalation of the substance can lead to fatal black lung disease. But it's also extraordinarily volatile.

"Coal dust is more explosive than methane," Oppegard says. "If you don't clean your mine properly, if there is a fire or an explosion, it can ignite coal dust, and then it travels throughout the mine, picking up force and energy. That coal dust is like gunpowder."

"There's absolutely no justification for arguing that a miner needs to go to management and tell them, 'You have accumulations of loose coal and coal dust,' when everybody can see it, including management," he continues. "Frequently, 103(g) complaints are made after miners have told management repeatedly and they don't do anything about it, and the miner finally thinks, 'Well, the only way to get attention is to call MSHA.'"

In addition to Bailey, IBT spoke with another miner at the Marshall County Mine who says he brought safety concerns to management -- only to be rebuffed. He spoke under condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. He says he filed 103(g) complaints over roof control, ventilation and dust accumulation on the belt line -- relatively common but serious safety hazards in coal mines.

"On the mine committee, they'll say, 'This ain't right, we'll take care of it,' but they don't ever take care of it," says Alan Bailey. "They pacify you, they tell you what you want to hear and hope like hell you go away. And when you don't, you're an a-----e because all you've done is caused them problems, and they're not getting coal they need to get, and we're not meeting contracts."

Murray Energy maintains that the "overwhelming majority" of safety complaints result in "negative findings." The company did not substantiate this claim in court or in response to questions from IBT.

Even so,Oppegard says negative findings aren't evidence of frivolous claims: Managers and workers might address the problem after a complaint is filed, or the inspectors might just miss it.

"The way that Murray looks at it is just because there's a negative finding, that means you had an ax to grind with the company and you were calling in a bogus complaint, and that's just way off base," he says. "But that's the way Mr. Murray views miners and the world in general -- that everyone's out to hurt his coal companies."

'It's A Question Of Power'

The coal industry has struggled in recent years. The spike in low-cost natural gas production and tougher regulations have weakened demand for the fossil fuel. Over the last two years, some of Murray's top competitors have entered bankruptcy proceedings, including Alpha Natural Resources and Patriot Coal. Layoffs, too, are commonplace.

But the CEO once dubbed "the last man betting on U.S. coal" insists he's not backing away from the industry. In a recent speech at a global coal conference in Spain, Murray projected that coal's share of the U.S. energy mix will continue to fall. "I want to be the low-cost producer of that market that's left," he said.

In his rise from small-time operator to corporate tycoon, Bob Murray has rarely shied from confrontation. His company has repeatedly clashed with labor regulators, environmental regulators and the mine workers' union.

Murray Energy led the first lawsuit against the Environmental Protection Agency over President Barack Obama's landmark plan to reduce emissions from coal-fired power plants. In October, it sued the EPA over its new ozone rule. Last year, it sued the Labor Department over regulations designed to reduce black lung disease.

Patrick McGinley, a law professor at West Virginia University, sees Murray's alleged warnings to whistleblowers as part of a larger struggle in the industry.

"It's a question of power," says McGinley, who served on a panel appointed by the governor of West Virginia to investigative the Upper Big Branch disaster. "It's intended to send a message that Murray Energy's got lawyers, they're powerful, they can bend the law to suit its goals and to make critics both inside the mines and outside Murray Energy think twice about challenging things the company does."

Whatever the company's motivations, Murray's combative spirit appears to extend to the recent lawsuit.

Months after the Labor Department filed its complaint in mining safety court -- and just days before the case was due for its first hearing before an administrative law judge in September -- Murray Energy subsidiaries filed a lawsuit of their own against the United Mine Workers in federal court.

It accuses the union of violating its collective bargaining agreement. In a statement, Murray Energy turned the safety allegations against workers, blasting the United Mine Workers for waging an "anti-management campaign, whereby they have refused to report allegedly unsafe working conditions to management."

The union declined to comment.

"There is a long history of UMWA-represented employees filing false safety complaints with the federal government to intimidate management," says Murray spokesman Broadbent.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.