Fossil Fuel Execs Have Little Financial Incentive To Fight Climate Change, Report Says

Marathon Oil Corp. CEO Lee Tillman took home a $1.7 million bonus last year, in part because of the company’s expansion into the Texas and North Dakota shale formations. Meanwhile, Exxon Mobil Corp. executives saw higher payouts, thanks partly to the oil giant's drilling campaign in the Russian Arctic. That’s life in the energy business. As major companies amass greater amounts of oil, gas and coal, top executives are often rewarded with bonuses and incentive pay — and environmentalists say that’s a problem.

Environmental groups say the energy industry's pay system is pushing companies to search for and extract more reserves -- no matter the carbon intensity or cost -- at a time when climate scientists are urging nations to leave fossil fuels in the ground to avoid catastrophic climate change. Critics argue that executive compensation plans should reward leaders for investing in alternative technologies or diversifying operations, rather than efforts that increase the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“The CEO pay system is one reason why the fossil fuel industry has been fighting so hard to continue a business model that’s locking us into a destructive path,” said Sarah Anderson, the global economy project director at the Institute for Policy Studies, a liberal Washington think tank.

Energy companies say their executive compensation programs are an important driver of success. For publicly held companies, rewarding leaders who improve financial performance and operational results is ultimately good for the shareholders, they say. Marathon Oil’s incentives and awards “align our executives’ interests with those of our stockholders,” the Houston-based oil and gas giant said in its 2015 proxy statement. “Our program is designed to reward executives for their performance and motivate them to continue to perform at a high level.”

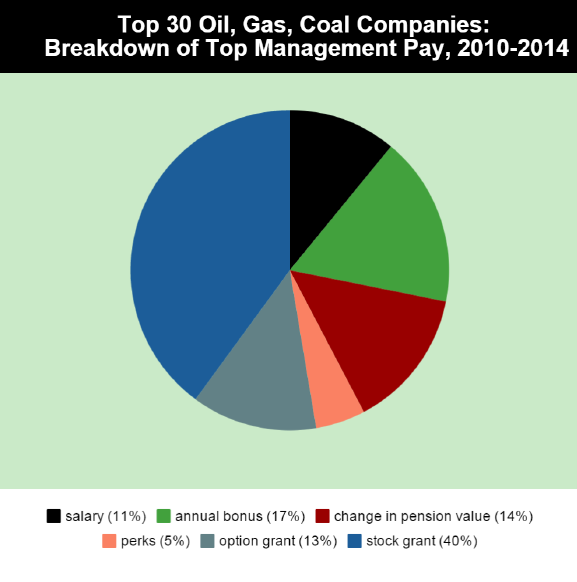

The CEOs of America’s largest public oil, gas and coal companies are among the highest-paid executives in the country. The heads of 30 top fossil fuel giants averaged $14.7 million apiece in total 2014 compensation, more than 9 percent higher than the $13.5 million average for the CEOs of S&P 500 companies, IPS found in a report released Wednesday. The top executives at Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips each earned more than twice the S&P 500 average.

Climate scientists say a substantial portion of the world’s remaining fossil fuel reserves must remain unburned in order to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels -- the target governments are striving to keep to avoid the most dangerous effects of climate change, including substantial sea level rise, violent and frequent storms and disappearing ice caps. Even a 2-degree rise will have serious effects in any case.

One-third of global oil reserves, half of natural gas reserves and more than 80 percent of coal reserves must remain unused from 2010 to 2050 to meet the 2-degree target, researchers at University College London estimate. “Our results show that policymakers’ instincts to exploit rapidly and completely their territorial fossil fuels are, in aggregate, inconsistent with their commitments to this temperature limit,” authors Christopher McGlade and Paul Ekins wrote in a January paper.

Yet at 13 of the top U.S. oil exploration and production firms, executives are rewarded with bonuses for expanding fossil fuel reserves, IPS found in its report. None of the 30 energy companies on their list offer bonuses for diversifying into renewable fuel sources or reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Other forms of executive compensation encourage a similar dynamic at energy companies. CEOs at many U.S. firms -- not just oil, gas and coal producers -- can cash in their equity-based pay, including stock options and stock grants, within three to four years. Since they can quickly reap such rewards, leaders are discouraged from developing a longer-term strategy to prepare the company for the effects of climate change or potential government policies to limit fossil fuel production, Anderson and other critics said.

Stock repurchase programs -- when companies buy their own shares back from shareholders-- can also deter fossil fuel companies from more sustainable business models, they say. Pouring profits into buybacks inflates the value of shares, further boosting equity-based pay for executives, and insulating leaders from broader market pressures, such as plunging oil prices and tighter federal regulations on coal-fired power plants.

Buybacks also take valuable investment away from research and development in alternative and renewable energy technologies, critics contend. The IPS report found 23 out of the 30 leading U.S. oil, gas and coal firms repurchased a combined $38.5 billion in shares in 2014, or nearly six times the $6.6 billion in "clean energy" R&D spending from private companies last year.

Environmental and financial-reform activists are pushing to end buyback programs and extend the time horizons for equity-based pay, so that executives must wait 10 years or longer before cashing in their stock options and grants. Shareholder advocates are pushing corporate resolutions that would break the link between a company’s fossil fuel expansion and bonuses for top executives.

“The reserves should not be a metric executives are rewarded on,” said Rosanna Landis Weaver, a project manager at As You Sow, a leading shareholder activist group. “They should be incentivizing their engineers to come up with the best solutions, instead of incentivizing them to waste more oil.”

Shareholder resolutions so far have done little to shift the way CEOs at energy firms are compensated. At Exxon Mobil, activists have introduced 62 climate-related resolutions over the last 25 years, all of which were successfully opposed by management. Still, the number of shareholder proposals continues to rise, with a record 433 social and environmental resolutions filed so far in the 2015 proxy season, As You Sow found.

Other groups are working from the outside to pressure changes within fossil fuel companies. The fossil fuel divestment movement, which is active on many college campuses, is urging individual investors, endowments and philanthropies to pull stocks out of oil, gas and coal companies, both to protect their assets from oil price swings and carbon regulations and to also send a signal that those firms are undesirable.

About half the 30 companies surveyed by IPS are also listed on a separate index of 200 fossil fuel companies flagged by divestment proponents. The companies are ranked based on estimates of the total carbon dioxide emissions contained in their reserves of coal, oil and natural gas. Combined, the firms hold nearly five times the amount of carbon that can be burned for the world to have an 80 percent chance of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, according to Fossil Free Indexes.

Concerns about executive compensation “are another layer of reason to get out of these companies, because this is not a fair-pay system,” said Vanessa Green, the global individual program director at Divest Invest, a Boston advocacy group.

Anderson of IPS added, “The pressure on the companies to make this transition is only going to mount, and if they were smart, they would be proactive,” she said. “They would be spending less time fighting Obama’s climate agenda and more time thinking about how to position their companies for the clean energy future.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.