Getty Images Lawsuits: Enforcement Or Trolling? Fear Of Letters Dwindling, Stock-Photo Giant Hits Federal Courts

What happens when a simple stock photo of a spider web with dew becomes a federal case? We’re about to find out, and then some.

A few weeks ago, Getty Images Inc. went on a lawsuit spree of sorts, filing federal copyright-infringement complaints over images it claims have been used without its permission. Court records show the Seattle-based stock-photography giant filed five single-image lawsuits in the month of January alone. The legal complaints are virtually identical, employing a cookie-cutter template differentiated largely by the names of the defendants and images in question. In one case, it’s a law firm accused of using a stock photo called “Businessman Falling Over, Legs in Air.” In another case, it’s a design company accused of swiping the aforementioned “Spider Web With Dew.” The list goes on.

Even for Getty Images -- a privately held company known for aggressively enforcing its copyrights -- the lawsuits are unusual. In many circles, Getty is already notorious for its dreaded “settlement demand letters,” which it routinely fires off to website owners suspected of using one of its images without permission. For the people and businesses that receive them, a simple cease-and-desist is not enough. Instead, Getty tells alleged infringers that it is their responsibility to “pay for the image(s) already used.” The letters are accompanied by an invoice, often in the amount of several hundred to thousands of dollars. If the letters are ignored, more follow, each more threatening than the one before.

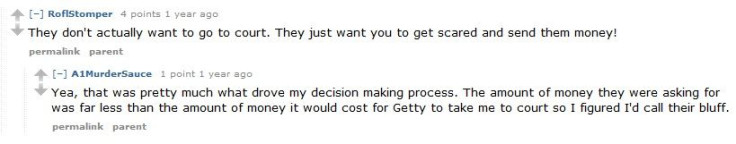

That practice has earned Getty Images a reputation for being a bully, an extortionist and a copyright troll. It’s so pervasive -- thousands of letters are sent out each year -- that it has sparked a virtual sub-industry of websites, blog posts and message boards devoted to offering advice for website owners on the receiving end of the ominous correspondence. At the same time, the wealth of first-person accounts now available online has, some say, softened the intended saber-rattling effect of Getty’s letters. Do a little digging, and you’ll soon discover the truth: Getty threatens, but it rarely sues.

At least not until now. Oscar Michelen, an intellectual-property lawyer who serves as legal consultant for the website Extortion Letter Info (ELI), said he believes the recent lawsuits are less about Getty protecting its copyrights than about preserving the reputation of its revenue-generating collection letters. “I think this is a way to counter the blogosphere,” he said in a phone interview. “There’s a lot of discussion on a variety of websites that, ‘Hey, if you get these Getty letters, they generally don’t follow up with lawsuits.’”

Getty itself didn’t argue with that assessment. In a statement provided to IBTimes by a Getty spokeswoman, the company admitted that the recent lawsuits were filed, in part, to “send the message that we will take legal action when someone uses our content and is not willing to pay a license fee.”

Michelen countered that everything about the lawsuits seems suspiciously calculated, from the cookie-cutter style of the complaints to the types of businesses Getty has chosen to go after, opting to sue law firms and website designers over “sympathetic defendants” like hobbyists or nonprofits. “I’m sure they wanted to avoid those types of defendants,” he said. “Who likes lawyers, right? So let’s go sue some lawyers.”

Although he would not comment on the specific cases, Michelen said he has agreed to represent three of the defendants recently slapped with Getty lawsuits. Over the past seven years, he’s also consulted thousands of website owners on the receiving end of Getty’s demand letters. He said he’s never known Getty to follow through with litigation before last month.

Matthew Chan, who founded ELI, had even harsher words for Getty’s recent spate of lawsuits, saying they reek of tactics employed by the shadowy copyright-litigation firm Prenda Law, which last year was sanctioned by a federal judge for filing boilerplate copyright complaints on behalf of pornographers. In an email to IBTimes, Chan said he thinks Getty’s strategy could backfire in a similar way. “They are using the court system as a collection mechanism with little intent on actually going forward,” he said. “Many judges have gotten wise to these trolling operations of using the court system as a tool to force out-of-court settlements. If Getty continues to do this, I believe they eventually will be ‘discovered’ and called out.”

Getty disagreed and said it has resorted to litigation only after repeated attempts to reach fair settlements. “We have no economic incentive to use the court process in place of a business process,” the company said. “The parties in these cases have refused to pay the appropriate licensing fees for the use of creative content that does not belong to them.”

In a lot of ways, the disagreement represents an all-too-common clash of modern-day mores. Founded at the dawn of the Internet age in 1995, Getty Images has toed a precarious line in its efforts to foster both innovation and consolidation in the stock-photography industry. Few would argue that the task of policing 80 million images in a copy-and-paste culture is not a difficult one. So vital has enforcement become to Getty’s bottom line that in 2011 it acquired PicScout, a company that creates software for tracking images across the Internet. That acquisition, coupled with Getty’s heavy-handed settlement tactics, has further fueled accusations from Getty’s critics who say the company is engaged in a massive revenue-generating collection scam.

But Getty is unapologetic. It says the amounts it seeks from alleged infringers are based on its actual license fees, plus a portion of its enforcement costs -- a financial hardship it doesn’t believe it should shoulder. “We do not believe it is reasonable that, upon being identified as having used an image without a license, an image user should only be accountable for the cost of licensing that image alone,” the company said. “If that were the case, there would be little incentive to license images properly in the first place, and we would be doing a disservice to our existing paying customers, and to our contributors who rely on the correct licensing of their images as a source of income.”

Michelen, who represents copyright owners for Cuomo LLC in New York, said it comes down to a matter of degree. “There’s a very big difference between copyright enforcement and copyright trolling,” he said. “What I think is going on with these letters is people are overpaying. They’re scared into paying more than the infringement is worth, and more than a court would allow.”

On that point, the recent lawsuits will undoubtedly serve as an interesting test case to see how well the federal courts will receive single-image copyright complaints filed in bulk. In most of the suits, Getty is seeking damages “in an amount to be proved at trial,” making the projected worth of the contested images unclear at present. Getty Images, for its part, cites its recent lawsuits as evidence that is working to protect intellectual-property rights and “the creative process of artists and photographers” around the world.

“It’s a shame that anyone who does this these days is labeled a troll,” the company said.

Got a news tip? Email me. Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.