Here’s How McDonald’s Avoided $1.2B In European Taxes After Shifting Operations To Luxembourg

A coalition of European and American trade unions has accused McDonald’s of skirting European taxes after the company altered the way it channels royalty payments from its restaurants in 2009. In a report released Wednesday, the group said the world’s largest restaurant chain avoided paying 1.06 billion euros ($1.2 billion) over five years by moving its European headquarters from the U.K. to Switzerland and channeling royalty revenue through a tiny Luxembourg-based subsidiary.

This and other strategies that allow companies to avoid European and U.S. taxes are employed by many multinational corporations. European Union authorities have criticized Ireland, the Netherlands and Luxembourg for cutting deals with companies such as Apple, Starbucks and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles.

“It is shameful to see that a multibillion-euro company that pays low wages to its workforce still seeks to avoid its responsibility to pay its fair share of much-needed taxes to finance public services we all rely on,” Jan Willem Goudriaan, general secretary of the European Federation of Public Service Unions (EPSU), said in a prepared statement.

In 2013, for example, McDonald's collected 833.8 million euros ($947.2 million) in European royalties but paid 3.3 million euros ($3.7 million) in taxes on this revenue, or 0.4 percent, instead of the 229.5 million euros ($260 million) it would have paid in the countries where the royalties originated, or 27.5 percent.

McDonald’s spokeswoman Becca Hary said in an email Wednesday that the company is abiding by all applicable laws, “including payments of the taxes that are owed in each country in which we operate. In addition to paying taxes on profits, we pay significant taxes for employee social contributions, property taxes on real estate and other taxes as required by law.”

In 2009, McDonald’s changed the way it processed royalty payments collected from its directly owned restaurants and franchises, an important revenue stream for the $94.7 billion global fast-food giant based in Oak Brook, Illinois. It also shifted its European headquarters from the U.K. to Switzerland, where corporate tax rates hover between zero and 12 percent for companies that derive most of their revenues from outside Swiss borders.

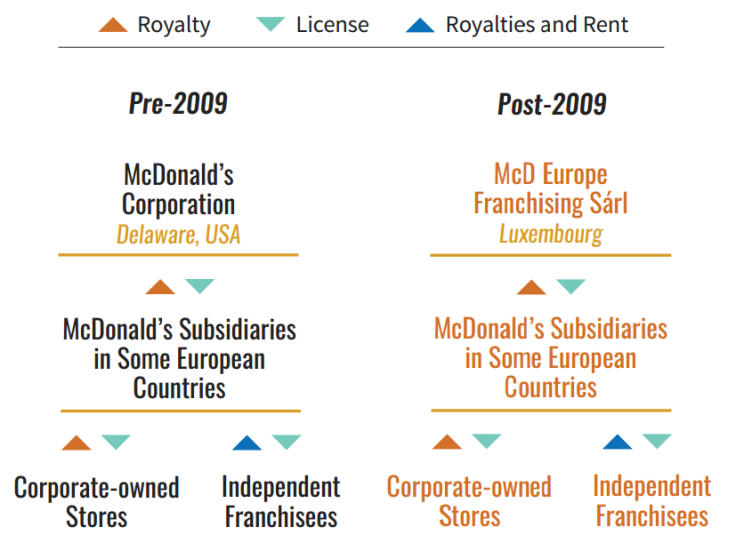

Before 2009, the McDonald’s stores' royalty revenue – the money each restaurant pays for the use of the McDonald’s brand – would be collected and sent to Delaware, where the company is registered. This exposed the money to U.S. corporate taxes. McDonald’s derived 41 percent of its total sales from Europe in its most recent quarter.

In 2009, the company shifted the revenue stream to a Luxembourg-based subsidiary called McD Europe Franchising Sàrl to take advantage of Luxembourg’s generous 80 percent tax exemption on royalties. Between these operations in Geneva and Luxembourg, McDonald’s dodged more than a billion euros in taxes, the group said, citing company financial data and the documents obtained in Luxembourg by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

Starbucks Corp., the world’s largest coffee chain, employs similar royalty-paying tactics that have allowed it to skirt British corporate taxes. Last year, Reuters reported that since 1998, Starbucks' U.K. subsidiary reported $4.8 billion in coffee sales and opened 735 outlets, but only paid $13.4 million in British taxes by siphoning profits into company subsidiaries in the Netherlands and Switzerland in order to report U.K. losses.

For a good primer on European tax-avoidance strategies, check out the ICIJ’s video:

These tax-avoidance laws may soon change.

Last year, the European Union announced it would close a loophole that allows multinationals to pit one European country’s efforts to attract business against a neighbor’s efforts to collect taxes on business activities within its borders. That loophole pertains to the relationship between a company and its subsidiary located in another EU member state.

"The aim is to close a loophole that currently allows corporate groups to exploit mismatches between national tax rules so as to avoid paying taxes on some types of profits distributed within the group," finance ministers said in a statement published by Reuters last year. Countries have until the end of 2015 to implement this change into their national laws.

However, closing tax loopholes is difficult, as each country works in its own interests to attract business and companies throw their financial weight behind lobbying efforts to keep loopholes open, as Apple has done in recent months.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.