High Risk Of Nuclear Disaster Caused By Fire At US Reactor Sites, Scientists Say

Following the 2011 tsunami that caused a nuclear disaster at Fukushima, Japan, and the consequent radioactivity that continues to this day, regulators in countries around the world took a look at the safety measures at nuclear facilities in their respective countries. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in the United States was no different, which approved a number of safety upgrades at reactor sites after a review.

However, in an article published Friday in the journal Science, three scientists argue the NRC review “relied on faulty analysis to justify its refusal to adopt a critical measure for protecting Americans from the occurrence of a catastrophic nuclear-waste fire at any one of dozens of reactor sites around the country.” The risk of fires is high specifically in the cooling pools of reactor sites, according to the article.

Read: History Of Safety Issues At Hanford Nuclear Waste Site

Edwin Lyman from the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington, D.C., and Michael Schoeppner and Frank von Hippel from Princeton University in New Jersey, say in the article’s abstract a screening process used by NRC “did not adequately account for impacts of large-scale land contamination events. Among rejected options was a measure to end dense packing of 90 spent fuel pools, which we consider critical for avoiding a potential catastrophe much greater than Fukushima.”

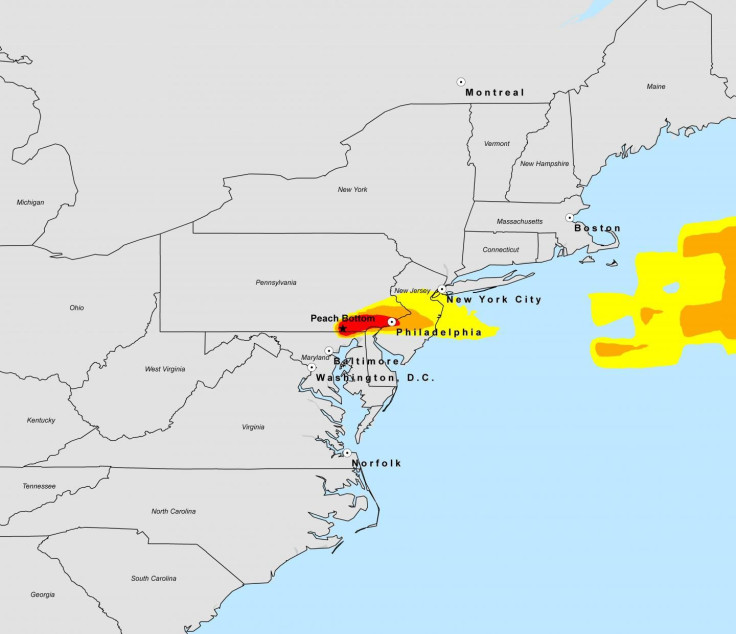

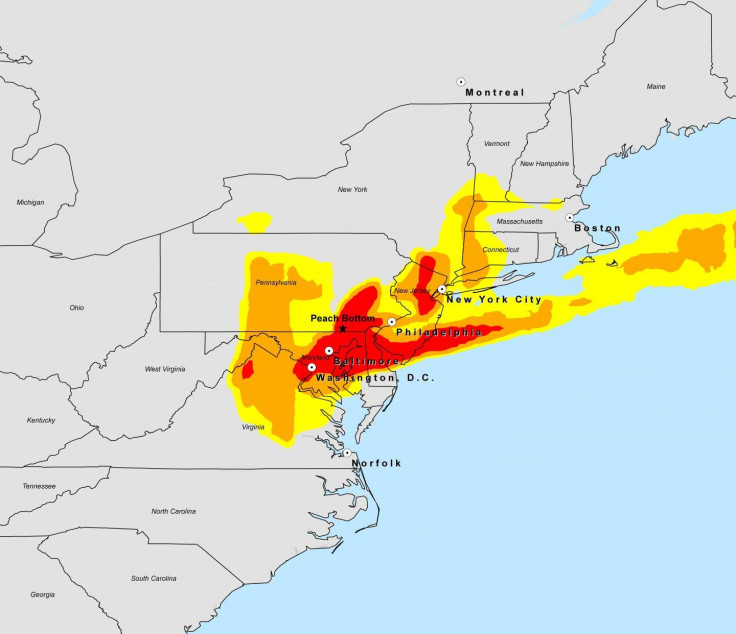

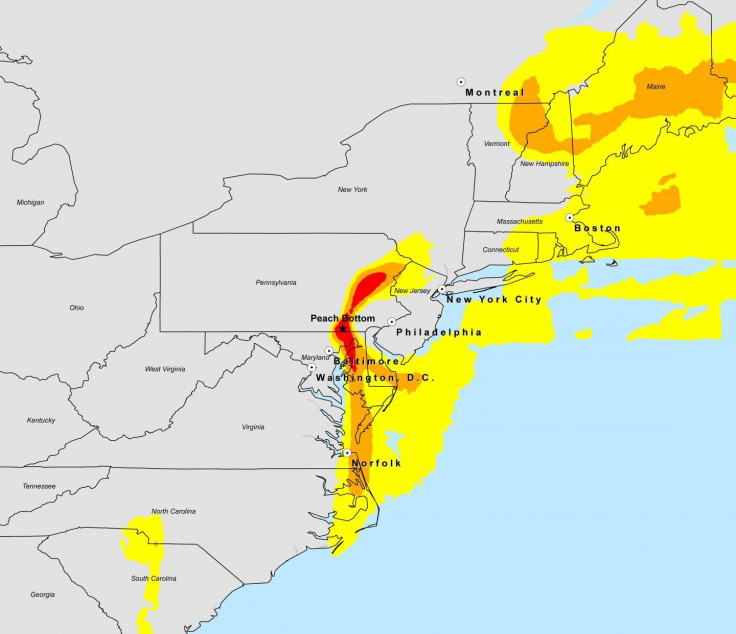

The cooling pools at nuclear reactor sites are basically large basins full of water, in which spent fuel rods, which are still radioactive, are stored and cooled. In a statement Thursday, scientists said the fuel rods are crammed in the pools, the density of nuclear waste so high that a fire could “contaminate an area twice the size of New Jersey. On an average, radioactivity from such an accident could force approximately 8 million people to relocate and result in $2 trillion in damages.”

Some of the catalysts for such a catastrophic fire include natural phenomena like earthquakes and human activities like terrorist attacks. Calling regulatory analysis by NRC biased, done under pressure from the nuclear industry, the researchers said the agency excluded the possibility of a terrorist act and the damage potential of a fire to areas more than 50 miles away from a nuclear plant.

“The NRC has been pressured by the nuclear industry, directly and through Congress, to low-ball the potential consequences of a fire because of concerns that increased costs could result in shutting down more nuclear power plants. Unfortunately, if there is no public outcry about this dangerous situation, the NRC will continue to bend to the industry’s wishes,” von Hippel said in the statement.

During its review, NRC found the potential damage from a fire at a cooling pool of an average nuclear reactor to amount to about $125 billion, and the agency assumed it would not have any consequences for areas outside a 50-mile radius. It also found that moving the spent fuel to dry casks could curtail the radioactive release from cooling pools by as much as 99 percent. Another assumption NRC made was that all contaminated areas could be cleaned up within a year after an accident, an assumption that is entirely inconsistent with facts from Fukushima and Chernobyl.

Read: Radiation From Fukushima Affected Everyone On Earth

Based on its findings and assumptions, the agency decided it wasn’t justifiable to impose a cost of building new pools — $50 million per pool — on nuclear plant operators.

The article’s authors pointed out that the Price-Anderson Act of 1957 limits the legal liability of the nuclear industry at $13.6 billion, meaning that in the event of a catastrophe, any costs upward of that (from a potential $2 trillion in damages) would be covered by U.S. taxpayers.

“Unless the NRC improves its approach to assessing risks and benefits of safety improvements — by using more realistic parameters in its quantitative assessments and also taking into account societal impacts — the United States will remain needlessly vulnerable to such disasters,” the researchers conclude.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.