Inmate Jail Deaths: As Families Search For Answers, An Opaque Criminal Justice System Stands In The Way

On the breezy, sunny morning of Jan. 10, 2007, Teresa Hazelton was folding laundry at her home in Stone Mountain, Georgia, when she saw an unmarked car driving from house to house. Curious, she walked outside.

“They asked if I happened to know Teresa Hazelton,” she recalled. “I said, ‘Yes, I’m she.’” A female chaplain and two police officers escorted her back inside the house. Her 19-year-old son, Joshua, an inmate in DeKalb County Jail, had committed suicide, they said simply. But Hazelton didn't believe them, especially after she saw photos from the mortician. “I knew he was killed, and I need to know why,” she said.

When a loved one dies in custody, by committing suicide or in other ways, some families are able to come to terms with the death and accept its stated cause. But others are unconvinced and even troubled by official explanations. The recent high-profile case of Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old woman found dead in her Texas jail cell last month in what officials ruled a suicide, has drawn attention to a systemic dearth of detail and lack of clarity about the circumstances surrounding the death of an inmate. The information vacuum can fuel families’ suspicions, pushing them to great lengths to extract answers from an opaque criminal justice system that often leaves them in an anguished struggle to understand how their child, sibling or spouse died.

“Access to official information is quite limited,” Eric Balaban, senior staff counsel of the National Prison Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, said. “Jails and prisons are closed systems. They’re very difficult to extract information from. ... Often, families are left with many unanswered questions.”

Bland's family said Tuesday it was filing a lawsuit after receiving little information following her death. Authorities said Bland hanged herself with a plastic bag, a finding the family disputes.

“I would welcome any additional information,” Geneva Reed-Veal, Bland’s mother, said in a news conference. “We've asked for it in writing, but we're not getting it."

NEW TONIGHT: Sandra Bland's family sues state trooper, wants answers. Read more here: http://t.co/NC8jIiD4Vw pic.twitter.com/pD44DjpSMx

— KTRE News (@KTREnews) August 5, 2015

Jails, far more so than prisons, can be conducive to inmate suicide. The suicide rate for the U.S. as a whole is 13 out of 100,000 people. In prisons, it’s slightly higher -- 16 out of every 100,000. In jails, the rate skyrockets to 40 out of 100,000.

Prison and jail systems often suffer from a lack of transparency, said Peter Perroncello, a former superintendent of jail operations in two counties in Massachusetts who now works as a jail management consultant in Boston. If families are unhappy with the answers they receive, or receive no answers at all, they should push for changes in state laws that would create a more transparent system, he said.

But in the current absence of such transparency, where some families never receive conclusive answers, the lack of clarity can prolong their anguish and bar them from finally gaining closure.

A Mother’s Pain

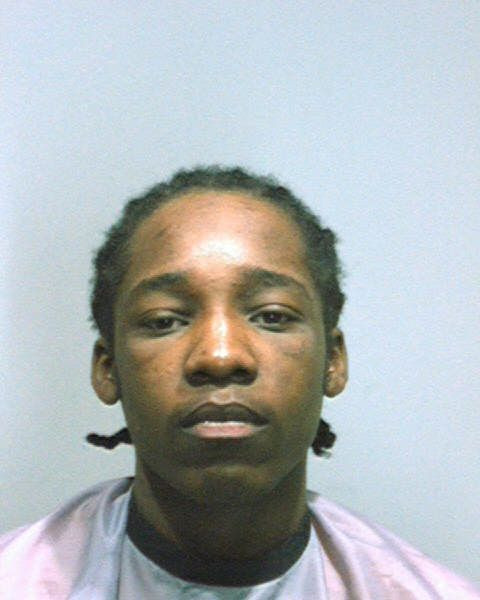

In January 2006, Joshua Hazelton was taken to DeKalb County Jail to await trial on murder charges. Two psychologists had declared him mentally unfit for trial, and less than three months before his death, a judge ordered that he be admitted to a hospital for psychiatric treatment. He attempted suicide in March of that year, and jail records also documented several psychotic episodes, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution later reported.

A medical examiner for the jail did not rule Joshua Hazelton’s death a suicide, even though his mother remembered being told that her son had killed himself. The jail autopsy report said that Hazelton's heart had stopped beating due to "undiagnosed schizophrenia," according to a lawsuit Teresa Hazelton later filed. But an investigator also noted that a white bed sheet had been tied in a square knot and "very loosely encircle [sic] the head."

Hazelton's mother has her own idea about what happened. “My son was murdered,” she said adamantly, citing photos from the morgue that she said showed the tips of his fingers broken and his front teeth jammed into his head. “He had broken ribs,” she added. “I mean, he was badly beaten.”

Hazelton said the lawyer in her lawsuit represented her case incorrectly. The suit, which argued that jail officials knew Hazelton’s son was at risk for suicide and had failed to prevent it, was effectively dismissed in 2012 with a summary judgment. “He just didn’t do things right,” Hazelton said of the lawyer, J.M. Raffauf, who goes by Mike.

Raffauf said he had no comment on the discrepancy between the murder Hazelton alleges took place and the suicide laid out in the lawsuit. He called Joshua Hazelton’s death “a travesty,” saying that the jail and courts had covered up the suicide of an inmate who was supposed to have been on suicide watch.

Thomas Brown, the DeKalb County sheriff who was named in the lawsuit and has since retired, said that Hazelton died of natural causes and his mother's "theories about how he died are totally unfounded." The DeKalb County sheriff's office did not respond Thursday to questions from International Business Times.

If the lawsuit failed in the legal system, it also left Hazelton, withdrawn, depressed and bereft of a son, still yearning for an explanation she considered acceptable -- something the jail hardly provided when the chaplain and officers came to her home in Georgia. “They didn’t give me any more details,” she said.

In the eight years since Joshua’s death, Hazelton has rarely spoken of it. In 2012, she moved from Stone Mountain, Georgia, to North Charleston, South Carolina. “I just kept it to myself. I could not breath,” she said. “I’m just -- it hurts.”

An Opaque System

When an inmate dies in custody, it is usually a police officer, sheriff, spokesperson for the sheriff or a chaplain who must inform the family. The conversation is difficult, for both parties involved. “It’s one of the worst things I’ve had to do,” Perroncello, the former Massachusetts jail supervisor, said.

The details shared in those phone calls or house visits tend to be sparse, both sides noted. But for the families, the lack of information is acutely painful.

Kevin Allen, a lawyer in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, estimated he has met with at least a dozen people whose family members have died in prison. “There’s very little information provided,” Allen said, and most of those families simply want to know how they can learn more about what happened. They are not necessarily looking to file lawsuits, he said.

Sometimes jail officials offer few details because they themselves have not pieced together the circumstances of a death. “We’re going to be mum about anything until we have the facts,” Perroncello said.

Concern about lawsuits is another common reason to hold back. “For us to divulge all the facts, it’s going to open us to litigation,” Perroncello said.

Authorities are also tight-lipped simply as a matter of adhering to bureaucratic protocol. In many states, for instance, suicide is a felony, which means that investigators, district attorneys or other officials must be notified before families can be told. Even the results of a concluded investigation are not ordinarily released to families, Perroncello said.

Eventually, suing can seem like a family's only option in order to access the results of an official investigation or to acquire a fuller of explanation of why and how their loved one died. “Many times the families have to resort to filing lawsuits to get the full picture,” Balaban, the ACLU lawyer, said.

One way for jails to prevent litigation is for officials to be as transparent as possible early on.

“Saying, ‘We have no comment,' only makes people more suspicious,” Lindsay Hayes, an expert on preventing suicide in jail and the project director of the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives, in Massachusetts, said. Families aren’t always seeking to make a fuss, he said.

“Sometimes they just want closure,” he said, but when officials don’t respond or refuse to disclose details, “people get very suspicious.”

Grasping For Answers

Sometimes, the circumstances of an inmate’s death are fairly clear. A man pitches himself headfirst over a second-story railing, or suicide notes are discovered after an inmate hangs himself.

In other situations, the details are murky. In 2013, 1.9 percent of inmate deaths in local jails were classified as "other/unknown," according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. In the past decade, the percentage of deaths with unknown causes has been as high as 10.5 percent.

In one case, a prisoner died after being put in a straitjacket and housed in a cell with a video camera, Allen, the Pennsylvania lawyer, recalled. Jail staff had also plunked a helmet on him, after he began banging his head. His death occurred during a crucial 90-minute stretch of tape that somehow went missing.

One expert ruled the inmate had died of positional asphyxiation, or when a person’s body position prevents him or her from breathing. Another said self-inflicted head injuries had killed him, Allen recalled. “The family thought something improper was done,” he added. “It was never really entirely clear.” The family could not be reached for comment.

In the majority of cases, a clear cause of death is eventually determined, Hayes said. Even if investigators and medical examiners initially disagree, “most times people come to a consensus about the cause of death,” he said.

Parents might be shocked and disbelieving upon learning a loved one has committed suicide but many eventually come to see it as the truth. "The family sometimes didn’t quite know what their son or daughter was going through immediately prior to the arrest and/or during the initial stages of incarceration, and didn’t realize how despondent they were, or how they might’ve outwardly appeared normal," Allen said. Sandra Bland, for instance, struggled quietly with depression.

Nearly a decade after her son's fatal stint in a Georgia county jail, Joshua Hazelton's mother is not ready to give up. She said she had begun searching for a new lawyer, to file another suit in the wrongful death of her son. “I need to find some peace,” she said. “I don’t want to keep suffering. I need the truth.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.