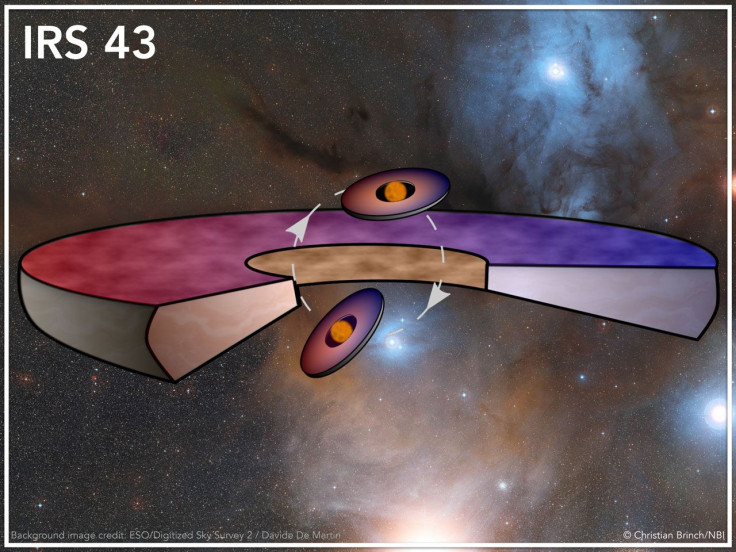

IRS 43: A Chaotic Binary Star System With 3 Skewed Planet-Forming Disks

In the cosmic scheme of things, binary star systems are quite common. Occasionally, both the stars in such systems can even have massive planet-forming disks of hot gas and dust cloud encircling them.

What has never before been observed is a binary system with three accretion disks — until now.

On Tuesday, a team of astronomers led by researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute from the University of Copenhagen announced the discovery of an utterly chaotic binary system — one where the two stars share a large accretion disk in addition to their individual disks.

Moreover, all three disks in IRS 43 binary system located nearly 400 light-years from Earth are misaligned in relation to one another, leading researchers to theorize that their formation may have occurred in exceptionally turbulent circumstances.

“The two newly formed stars are both the size of our sun and they each have a rotating disc of gas and dust similar to the size of our solar system. In addition, they have a shared disc that is much larger and crosses over the other two discs,” Christian Brinch, an astrophysicist at the Niels Bohr Institute and lead author of a study detailing the findings, said in a statement. “All three discs are staggered and this breaks with everything we have seen so far.”

The stars in the system — observed using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile — are just 100,000 to 200,000 years old, making them much younger than our 4.5 billion-year-old Sun.

So what could have created such a turbulent and chaotic system?

The answer, for now, remains unknown. The researchers plan to create computer simulations to understand why the accretion disks in the system are so skewed, and to comprehend the physics of the formation process.

“Perhaps it is a dynamic process of formation, which happens often and then it corrects itself later on. We will try to clarify this,” co-author Jes Jørgensen, also from the Niels Bohr Institute, said in the statement. “We will also apply for more observation time on the ALMA telescope to study the planet-forming discs in even higher resolution to get more detailed information about their chemical composition.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.