J-1 Visa Abuse: Employers Exploit Foreign Students Under US Government Program Meant For Cultural Exchange

What drew Khrystyna Mylkus to the U.S. State Department’s cultural exchange program was simple: She wanted a taste of American culture. The 17-year-old Ukrainian envisioned the ultimate foreign adventure, working for the summer at a popular theme park with college students like herself and traveling through parts of the U.S. she had only read about back home. Instead, Mylkus’ J-1 visa offered an American experience of a different kind — a firsthand immersion into the life of an overworked, poorly paid laborer with little job stability.

After Mylkus paid more than $3,000 in recruitment charges, visa fees and travel expenses, she spent much of last summer maintaining a 48-hour work week, making beds and cleaning bathrooms at a lodge in Isle Royale National Park, a remote island resort in Lake Superior. Mylkus returned to her studies in Poland in September with $600 and little else to show for it, according to a complaint filed recently to the U.S. State Department against GeoVisions, a Connecticut-based cultural exchange coordinator that acted as Mylkus’ sponsor.

“They told me this would be a great opportunity to learn a new culture, to speak with real Americans, to improve my English,” Mylkus told International Business Times in a heavy Eastern European accent. “But these jobs should be in a city and they should not include jobs like housekeeping with other foreign students, because you don’t get very much time to interact with Americans.”

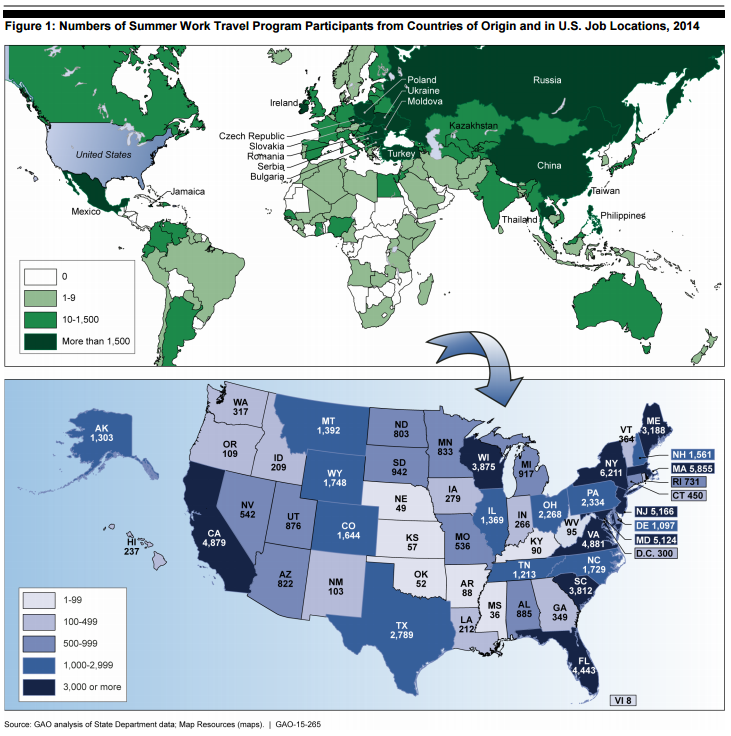

Labor rights advocates say the J-1 Visa Exchange Visitor Program, not unlike the U.S. government's other visas — including the H-2 , H-1 and B-1 — allows American employers to exploit foreign workers. The department’s guest worker visa programs attract more than 1 million foreigners each year. Some 200,000 of them come on J-1 visas under a cultural exchange program created in the early 1960s. Employers sometimes force the guest workers to live in crowded housing conditions and work erratic schedules, ranging from a couple of hours a week to 25-hour shifts. Many workers also complain of wage theft.

The State Department explicitly forbids J-1 holders from working in the adult entertainment industry or as household domestics, because those jobs lend themselves to the exploitation of foreign workers. But the department only stops short of a ban on placing J-1 students in modeling agencies, housekeeping work and janitorial services .

Jacob Horwitz, organizing director of the New Orleans-based National Guestworker Alliance, says like other guest workers, J-1 participants of the program’s summer work-travel component are under intense pressure to stay silent when they face abusive labor conditions. He says that for every guest worker who airs grievances there are many others who don’t.

“J-1 sponsors control student workers' immigration status,” Horwitz says. “These sponsors often work closely with employers and frequently threaten to cancel a workers' status when workers make complaints or try to change conditions at their workplace. Because of these implicit and often explicit threats it takes a brave group of workers to come forward and report abuse in the J-1 visa program.”

A Summer-Long Saga

Earlier this year, Mylkus accepted a job offer through GeoVisions working as a food-preparer at Busch Gardens, an amusement park in Williamsburg, Virginia. It was an enticing offer. She’d make only $7.90 per hour, but GeoVisions said she would be working with other foreign students and interacting with American families while saving up for travel toward the end of her stay. But GeoVisions failed to verify Busch Gardens’ age requirements. Mylkus was 17 at the time, as stated on the copy of the passport she provided to the sponsor before she traveled to the U.S.

It wasn’t until she arrived on June 4 that she was turned away from the job because the park said it doesn’t employ J-1 workers under the age of 18.

“We make it very clear to our J-1 sponsor organizations and to summer work travel students applying for positions with the park that individuals must meet a minimum age requirement to live in our student housing village,” park spokesman Kevin Crosset said in an emailed statement.

Mylkus accepted Busch Gardens’ offer to allow her to reside in the park’s J-1 student housing facility for a few days, and then traveled—alone—60 miles away to the crowded seaside boardwalk of Virginia Beach to find work. Employers there wouldn’t hire her, she says, because they were concerned about her legal status. With her money running low, she reached out to former neighbors from Ukraine who had moved to Philadelphia. They offered her a place to stay while GeoVisions attempted to find her an alternative job. So she left Virginia and traveled north, jobless and running out of cash in a foreign country.

Nearly a month after her arrival and with lingering fears about her legal status, Mylkus accepted a job that GeoVisions found for her in Michigan’s Isle Royale National Park —some 1,300 miles away from her intended destination. GeoVisions paid half of the $300 she spent traveling from Pennsylvania. Adding to Mylkus’ problems, she claims the employer at the national park Rock Harbor Lodge never issued her last paycheck.

The lodge did not respond to numerous calls for comment.

GeoVisions remained in constant email contact with Mylkus during her summer-long saga, as required by the rules of the program. Kevin Morgan, CEO of GeoVisions, declined to comment on Mylkus’ situation, citing client privacy concerns. He also wouldn’t comment on the company’s relationship with Go2USA, the Poland-based recruiter Mulkus first approached that connected her to GeoVisions.

“We do, however, stress that protecting the health, safety and welfare of every student is paramount in everything we do,” Morgan said in an emailed response.

A History Of Problems

GeoVisions is one of 41 J-1 sponsor organization the State Department authorizes to participate in J-1 visa program. These groups make money by collecting fees from applicants and overseas agents like Go2USA. Sponsors pay government dues to be part of the program to help defray regulation costs. Students pay fees and travel expenses and the jobs they take are supposed to offer both cultural-exchange opportunities and a source of income for travel expenses. Employers benefit from the low-cost seasonal labor the students provide.

In 2013, the State Department reprimanded GeoVisions after it placed 15 students in line cook and cashier positions at a McDonald’s fast food restaurant in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Working conditions were so deplorable that McDonald’s Corp. forced franchise owner Andy Cheung to sell his six restaurants and the U.S. Department of Labor fined Cheung $211,000 in unpaid wages, damages and penalties. GeoVisions was censured for violating the conditions of the J-1 program and reduced the number of exchange visitors it could process by 15 percent.

The Southern Poverty Law Center, an Alabama-based legal advocacy group that specializes in civil rights cases, has chronicled a history of problems with the J-1 program. The nonprofit alleges that many employers prefer placing foreign students in hotel housekeeping and other jobs because the seasonal temp workers can’t quit without jeopardizing their legal status.

Since 2010, the U.S. State Department has made numerous attempts to reel in the abuses of the J-1 visa program. Three years ago, the government banned the recruitment of adult entertainers and domestic help and required sponsors to vet employers and to remain in contact with their J-1 students.

But labor advocates say the State Department didn’t go far enough and that it should also prohibit other job categories like housekeeping, cleaning services, fast food service and factory-like assembly operations because they don’t fit the spirit of the J-1 program. Students, they argue, should have meaningful cultural interactions with Americans as part of their jobs, quality work-life balances instead of grinding hourly work in kitchens or dirty hotel rooms and insightful planned cultural activities as required by the rules of the program.

While the U.S. government has resolved some of its issues with the program, a U.S. Government Accountability Office report released earlier this year cited lingering areas of concern, including an inability to track how much sponsors and their overseas agents are charging students, limiting the U.S. government’s ability to protect J-1 participants from excessive and unexpected costs.

The report also said students can find themselves working essentially as seasonal foreign temporary workers, much like the ones who come to the U.S. on H-2B visas, rather than participating in authentic work-travel experiences. The State Department “cannot assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of participants’ cultural opportunities outside the workplace … the program’s work component has often overshadowed its cultural component,” the report stated.

“The State Department takes seriously and investigates complaints regarding the J-1 Exchange Visitor Program,” a spokesperson for the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs said in an emailed statement in response Mylkus’ complaint.

“The primary goal of the Exchange Visitor Program,” the statement continued, “is to allow participants the opportunity to engage broadly with Americans, share their culture, strengthen their English language abilities, and -- if there is a work or training component -- learn new skills or build skills that will help them in future careers.”

Meredith Stewart, staff attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center who co-wrote Mylkus’ complaint against GeoVisions, points out that employers also prefer J-1 students because unlike other foreign guest workers, employers aren’t required by labor regulations to reimburse visa and travel expenses. This makes J-1 guest workers less costly to employ. “So we’re seeing employers using these two guest-worker programs interchangeably,” Stewart says. “We’re also seeing J-1 workers working alongside H-2B workers.”

Stewart pointed to a case in 2011 in Biloxi, Mississippi, where 11 students from Peru and Brazil paid thousands of dollars to participate in the J-1 exchange program only to find themselves working alongside H-2B laborers from the Philippines, Jamaica, Belarus, Indonesia and Turkey at a popular local casino resort.

Defenders of the J-1 program, and there are many, point out that it largely conforms to the sprit in which it was founded under the Fulbright–Hays Act of 1961 .

Olena Kulbaba, a 29-year-old from Kiev, Ukraine, says she improved her English and traveled when she participated in the program twice: once in 2008 at Tybee Island, Georgia, and then in 2009 at Hilton Head, South Carolina.

She says she avoided some of the pitfalls others encountered by being vigilant and not trusting everything local recruiters and U.S. sponsorship organizations told her. She says foreign students should also investigate employers before accepting any offer, including how much they deduct from paychecks for the housing they provide.

“What I want to warn people who want to come on J-1 is that you need to check the employer before you come, because sometimes they take advantage of you,” she says. “Some will not give you the hours you need and some will take lots of money from you for a really sh---y apartment.”

Mylkus offers her own advice.

“If I did this again, I would not do it alone,” she said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.