Kevin Sabet Is The Marijuana Movement's Biggest Threat, But Can He Really Stop 'Big Pot'?

BETHESDA, Maryland -- Kevin Sabet, the man Salon called the quarterback of the new anti-drug movement, the guy Rolling Stone labeled the No. 1 enemy of marijuana legalization, the 36-year-old political wunderkind whom High Times has declared the devil himself, takes the stage in a sprawling conference hall at the annual conference of the Association for Addiction Professionals (NAADAC) and gazes with confidence over his audience. But what comes out of the mouth of the founder of the three-year-old nonprofit, Smart Approaches to Marijuana, or Project SAM, isn’t typical anti-marijuana rhetoric.

“We cannot be Reefer Madness 2.0,” he tells his audience. “We went overboard.” Sabet doesn’t suggest marijuana is a gateway drug, doesn’t resort to scare tactics like the “This Is Your Brain on Drugs" public service announcement from the 1980s. In fact, Sabet agrees with his pro-marijuana opponents on many matters. He’s opposed to harsh drug laws that have long criminalized people – mostly minorities – for smoking or possessing small amounts of marijuana. He concedes that components of marijuana might hold medical promise and wants the federal government to make it easier to study the plant. And, most strikingly, he concedes the war on drugs was a failure.

But he’s not willing to give up the fight. He’s launched a new war against marijuana legalization, one focused on a new bogeyman. “These are the guys who keep me up at night,” he says with dramatic flair during his presentation, clicking to a slide depicting not ominous drug dealers or disheveled hippies, but three slick-looking guys in suits and ties. They’re the co-founders of Privateer Holdings, a powerful marijuana private equity firm. (With his boyish, clean-cut looks and thickset frame swaddled in a jacket and tie, Sabet would fit in among the trio.)

“In my mind, legalization equals commercialization,” says Sabet, explaining that legal cannabis will lead to the rise of corporations whose bottom lines will be tied to promoting the use of an inebriating and habit-forming substance. Like the alcohol industry, these marijuana businesses will target excessive users. “This is the addiction business,” he says. “The industry has an incentive to encourage heavy use.” And like the tobacco industry, marijuana businesses will try to hook potential customers when they’re young – hence the growing ubiquity of marijuana-infused gummy bears and other candies.

It’s a compelling argument: Our country has already allowed the mass commercialization of two intoxicating substances, alcohol and tobacco, which together cause more than 500,000 U.S. deaths and $500 billion in social costs each year. Do we want to follow the same path for marijuana?

Now, more than ever before, the country may be ready to embrace Sabet’s line of reasoning. A legalization initiative in Ohio that would have granted an oligopoly to its deep-pocketed funders failed at the polls in November, but not before shifting the national dialogue around cannabis. Media outlets are reporting on the rise of “Big Pot" and marijuana advocates are bemoaning the fact that the country is entering a new era of cannabis reform in which “industry is taking over the legalization movement.” Sabet says the Ohio initiative has energized him and led to several new Project SAM donors.

"There’s a real tipping point here,” says Sam Kamin, marijuana law professor at the University of Denver. “It’s whether the industry runs this going forward or the policy wonks do. There’s real room for Sabet and others to say, ‘Let’s keep this from being tobacco and alcohol.’”

All it might take for the marijuana movement to lose ground is someone like Sabet, who has launched Project SAM chapters in three dozen states, to capture the hearts and minds of the people he calls “the marijuana middle,” the vast majority of Americans who don’t smoke pot but also don’t want to put people in jail for it. This could be why cannabis advocates are so antagonized by Sabet; maybe, deep down, they know he has a shot at stopping them.

But can Sabet even capture the hearts and minds of addiction specialists? At the end of his NAADAC conference presentation, he draws a hearty round of applause – from the 60 or so people in attendance. It’s a small fraction of the crowd the conference hall can hold.

The moderate turnout hints at the challenges that lie ahead for Sabet. While his kinder, gentler opposition to cannabis could be just what the anti-marijuana movement needs, with more than half of Americans now supporting legalization, are such efforts too little, too late? And if Sabet really has a realistic plan for marijuana that avoids both of hysterical excesses of the war on drugs and the corporate hazards of all-out legalization that the majority of Americans could get behind, why so often does it feel like he’s fighting this war all alone?

Driven to Compete

“Marijuana is more potent, it’s being marketed to kids, heavy use is at record highs … ”

It’s several hours before Sabet’s NAADAC presentation, and he’s hunched over a laptop in the 14th floor executive lounge of JW Marriot in downtown Washington, D.C. Through the lounge’s sweeping windows, the Washington Monument pierces the early morning sky. He’s prepping for several packed days of meetings and presentations, going over key talking points he has to hit not just at the addiction professionals convention, but in sit-downs with staff at the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy, a drug court judge and other power players.

This is what Sabet does: He roves all over the country and beyond on the dime of the various policy groups that have invited him, hammering home key facts and figures. But right now he’s being extra diligent with his preparations. He only has three days here in D.C., where the future of national drug policy will be decided, before he’s off to his next excursion, to Ireland. It’s imperative he’s at the top of his game.

Usually the Kevin Sabet show is a solo operation, but this morning he’s joined by two Project SAM staffers, both recently hired. One is Jeff Zinsmeister, a former State Department narcotics affairs officer in Mexico who left a consulting job at Bain & Company to work for Project SAM. The other is Will Jones, who at 24 launched “Two Is Enough,” an organization that tried – and failed – to stop D.C.’s marijuana legalization initiative in 2012.

Zinsmeister and Jones look tired as they help Sabet finalize a PowerPoint presentation. At one point Jones makes a run for coffee. Sabet passes on the caffeine. He’s wide awake and ready to go, even though he got in late last night after a flight from Melbourne.

Sabet has always been like this: driven to compete, driven to win. “The guy is always on,” says Zinsmeister. Buoyant and approachable, albeit well-versed enough in politics to stick to the script, Sabet likes telling stories of how he actively chats up hardened opponents, dismantling their assumptions of “the devil Kevin Sabet.” His wife Shahrzad, a postdoctoral fellow in international affairs at Harvard University, says she fell for him when they were both studying at the University of Oxford in 2004 because of his sincerity – “He totally wears his heart on his sleeve,” she says – compared to the slick alpha males she was used to at the institution.

But Sabet also has an aggressive side, one that arises and flourishes on the debate stage. His mentors vividly recall the moment when, at an Orange County, California, event, 17-year-old Sabet faced off against local Superior Court Judge James Gray and wiped the floor with the libertarian drug war critic. And his supporters speak in reverential tones of his ability to verbally spar with the marijuana movement’s most eloquent advocates. “He is probably one of the best debaters I have ever seen,” says Christine Miller, director of Project SAM’s Maryland chapter.

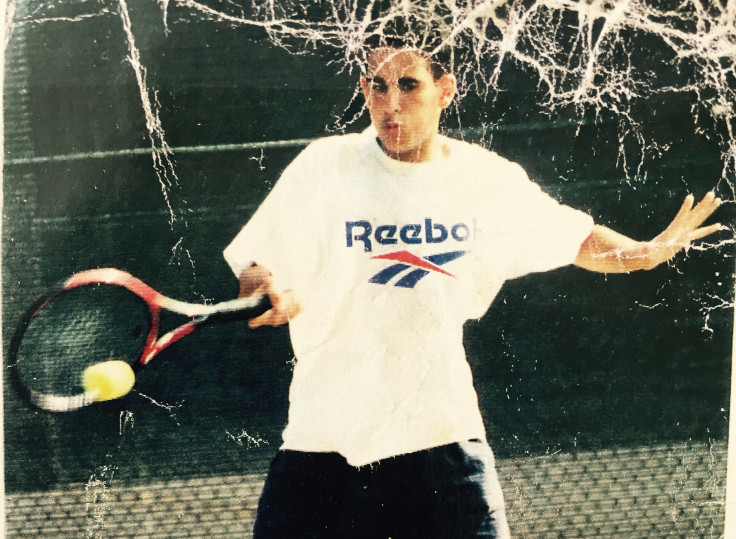

Sabet’s competitive streak was honed on the tennis courts of the upper-middle class southern California suburb in which he grew up. He was known for besting more powerful players who underestimated him, for thriving when all hope seemed lost. He did it all as a singles player.

“I hated doubles,” he says. “I didn’t want to let my partner down, and I wanted to rely on myself. I was going to go down alone or triumph in victory.”

His interest eventually shifted to another competition: Fighting marijuana. His crusade was inspired by a tragedy in high school. “A friend of his in school was killed in a drug-related car accident,” says his older sister, Mina Sabet. “He felt very passionate about it and wanted to find out the reason for it.” It’s the sort of anecdote that Sabet could use for political leverage, but he won’t go into details. “I don’t want to talk about my friend out of respect to the family,” he says.

The son of Iranian immigrants, avoiding alcohol and drugs was part of Sabet’s Baha’i faith growing up. But the stories his parents told of social injustices in their home country made him reluctant to fully embrace the strict criminal penalties of the war on drugs. “Our own family experienced persecution in Iran,” says Homa Tavangar, his older sister. “We grew up with a very strong sense of social justice, and taking a very big stand around issues like human rights.”

Becoming an anti-pot advocate at a young age was at times a lonely endeavor for Sabet, but it also got him noticed. “He always stood out,” says Robert DuPont, first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and one-time drug czar, who was one of Sabet’s mentors. “He was never like other people. You meet him and he is so clear on the issues, so outspoken, so against the stereotype.”

Launching Citizens for a Drug-Free Berkeley while an undergrad at the famed freewheeling school helped land Sabet a research job with President Bill Clinton’s Office of National Drug Control Policy, then another drug policy position under President George W. Bush. Finally he became a senior adviser to President Barak Obama’s first drug czar. He had high expectations for Obama’s marijuana policies. “I saw legalization coming down the pike, and I hoped this president didn’t get distracted by these really seductive arguments,” he says.

But instead there were setbacks, including the 2009 “Ogden Memo,” the Department of Justice notice that U.S. attorneys shouldn’t prosecute those in compliance with state medical marijuana laws, a memorandum that fueled dispensary industries around the country. According to Sabet, the memo blindsided the Office of National Drug Control Policy, triggering what he remembers as “pit in my stomach.”

The Ogden Memo was the turning point for Sabet. Marijuana advocates suddenly seemed more politically savvy, replacing buzzwords like “legalization” with more palatable options like “taxation and regulation.” In the fall of 2011, he left his job with the Obama administration to adopt his own approach to anti-marijuana advocacy. He recruited two contrasting heavyweights to his cause: Patrick J. Kennedy, the former Democratic U.S. representative from Rhode Island whose struggles with drugs and alcohol inspired him to become a steadfast anti-legalization proponent, and David Frum, a neoconservative speechwriter for George W. Bush. With their help, he launched what he titled “the third way” on marijuana policy, instead of outright criminalization or legalization.

“We had lost the middle,’” he says. “We had to rebrand.”

The Third Way

In January 2013, two months after Colorado legalized recreational marijuana, Sabet and Kennedy launched Project SAM in Denver. “We’re opening the doors to allowing a new, powerful industry to downplay the effects of a substance they will be profiting off of and to downplay the effects of addiction,” Sabet told the media at the time.

While the United States generally accepts big companies running major industries, Sabet argues a line should be drawn for potentially addictive products like marijuana. “Big Tobacco was a disaster for our country in terms of the marketing machine that was activated, while the government looked the other way for a century,” he says. “Do we want to repeat that with yet another substance? And one that in fact, unlike tobacco, produces intoxication and therefore leads to car crashes, workplace accidents, school dropouts and mental illness?”

It’s why Project SAM opposes any form of legalization. But then what does the organization want in its place? Sabet has repeatedly promised to develop model laws, but so far, policy proposals encapsulating Project SAM’s preferred legal reforms, such as reduced marijuana arrests and increased public health campaigns and treatment options, haven’t materialized.

“What do they want as a policy?” says Tom Angell, chairman of the pro-legalization group Marijuana Majority. “They make these assertions, how it’s something in the middle, but it’s very vague.”

Sabet says his organization has been working with drug-law experts and political consultants on the matter, and Project SAM-backed policy initiatives are coming soon. “We have to go on the offense,” he says. “I am sick of saying, ‘Vote no, vote no.’ We want to be ‘yes.’”

Sabet insists these proposals will be a major shift from the punitive “War on Drugs” approaches of old, including policies he worked on as a White House adviser. But some of his opponents wonder if his evolution is simply political expediency. “For many, many years he was a major driving force behind jailing and demonizing marijuana users,” says Brian Vicente , a Denver marijuana attorney who co-authored Colorado’s 2012 legalization initiative. “Now that public opinion has shifted away from the drug war, he has attempted to rebrand himself as the ‘Smart,’ middle approach, without acknowledging his past.”

Then there’s the fallout Sabet predicted from the country’s first experiments with legalized marijuana, how he promised in 2014 that in Colorado, people should expect “criminal organizations to adapt to legal prices,” “our teens to be bombarded with promotional messages from a new marijuana industry seeking lifelong customers” and “the social costs ensuing from increased marijuana use to greatly outweigh any tax revenue.” Two years in, has the doom and gloom he foretold come to pass?

Sabet and others point to reports concluding that problems such as marijuana use among youth, cannabis-related hospitalizations and marijuana traffic deaths have all increased since Colorado legalized marijuana. But others argue these reports feature selectively parsed data to suit the authors’ purposes, and note that other studies indicate marijuana might lead to reduced driving fatalities and underage use.

The sky hasn’t fallen in Colorado or Washington State since marijuana became legal, concludes Jonathan Caulkins, a Carnegie Mellon University professor who studies marijuana policy. But that’s because, he says, it’s too soon to determine the social impacts of the policy change. He thinks that anyone who tries to spin the short-term data to either promote or condemn legalization is missing the bigger question: What happens years from now to the first generation to grow up not just with legalized but potentially mass-marketed cannabis?

“Only an idiot would predict that the problems would come in two years,” says Caulkins. “I think we are going to legalize this nationally, we are going to let Big Tobacco play, and 25 years from now we will say, ‘What were we thinking?’”

A Thousand Kevins

As his three-day Washington, D.C., junket progresses, Sabet and his two-person Project SAM entourage ping-pong from one appointment to the next. As an Uber driver transports the trio to the NAADAC conference, Sabet conducts a news interview with a British journalist over his cell phone while Zinsmeister and Jones tweak their boss’ conference slideshow. At the convention center in Bethesda, Maryland, the three grab granola bars and potato chips from a Starbucks to make do for lunch, then power-walk through the facility, looking for the right conference hall.

Throughout their exploits, there’s talk of money. Before the insurance association meeting, the three brainstorm as to how best ask for financial support. After Sabet’s NAADAC talk, Jones suggests they acquire a smartphone credit-card reader, so they can take donations from inspired audience members after future speeches. As they are driven through posh D.C. suburbs, they admire the sprawling residences, making cracks that “multimillion-dollar drug warriors” like themselves should get mansions like these.

Project SAM’s opponents have long wondered who is paying the nonprofit’s bills. Critics have scrutinized the fact that when Project SAM first launched, it received support from Community Alliances for Drug Free Youth, a California nonprofit that’s received funding from the Federal Drug-Free Communities Act, which means the organization could have a financial interest in preserving the country’s current drug policies and related grants. And they’ve pointed out that Project SAM appears to enjoy a cozy relationship with several local DEA task forces, which have long operated as an advance guard in the country’s war on drugs.

Sabet’s detractors also make note of the fact that Stuart Gitlow, an outspoken member of Project SAM’s board of directors, is the medical director for a pharmaceutical company marketing Zubsolv, a drug designed to treat opioid addiction, and that Robert DuPont, Sabet’s mentor, helps run a consulting firm specializing in drug testing management. Sabet himself was an advisory board member of the Drug Free America Foundation, an organization founded by Mel and Betty Sembler after they shut down STRAIGHT, Inc., a highly controversial drug treatment company. Drug manufacturers and drug testing companies are also major sponsors of anti-marijuana organizations like NAADAC. Could they be bankrolling Project SAM, too?

Sabet insists that his organization receives zero funding from pharmaceutical companies, drug-testing interests or the government, although some of his trips and talks have been financed by organizations that do. And while Project SAM hasn’t yet filed taxes for 2014 – the first year the 501c3 nonprofit was in operation – Sabet says that when it does, the records will show an annual operating budget of around $100,000, funded entirely by small donations and a few larger contributions from organizations like the Bodman Foundation and Patrick Kennedy’s Kennedy Forum. While recently new funding sources have allowed Project SAM to make two additional hires in Washington, D.C., the organization is still far from flush with cash. “On one hand, it’s a badge of honor how much we have done with so little,” says Sabet. “On the other, it’s kind of embarrassing.”

Project SAM’s financial situation isn’t just embarrassing; it also highlights just how much has changed since the days of bush-league cannabis activists going up against the war on drugs machine. In 2013, the Marijuana Policy Project posted $1.6 million in revenue, while the Drug Policy Alliance boasted over $9 million, and these organizations have used their coffers to outspend their opponents on major legalization initiatives by a factor of 10 or more. And while reporters now have a plethora of pro-marijuana spokespeople they can mine for comments on the importance of legalization, on the anti-legalization side, they mostly just have Sabet. While the head of Project SAM may be a capable spokesman, is his voice powerful enough?

“When we had the ‘Just Say No’’ press on drugs, we had the first lady leading the charge, and that’s powerful,” says Tom Gorman, director of the Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area and longtime drug-war soldier. “The anti-legalization side doesn’t have that crusader that people are going to look to follow right now, and that’s a real deficit. Kevin’s not a radical; he is very reasonable; he is looking at the science, but he’s just Kevin Sabet trying to do the right thing.”

Late on his first day in Washington, D.C., Sabet returns to the JW Marriot’s executive lounge to unwind over a club soda. He doesn’t drink, but it’s clear the long day is getting to him. His polished talking points slip away, and anger seeps into his voice. But he’s not mad at pro-marijuana advocates, the ones he’s endlessly battling. He’s mad at anti-marijuana activists, or rather the lack thereof.

“I want there to be a thousand Kevins,” he exclaims. “There can’t be just one Kevin. Kevin is not going to be able to do this alone. Kevin can’t just do this year after year, he is going to have a heart attack.”

Running Out Of Time

After his D.C. lobbying trip, Sabet flies to Dublin followed by London for meetings and presentations, then he’s off to upstate New York for a fundraising event. After that, there are strategy meetings in San Diego, followed by a trip south to speak at a conference in Mexico before returning to New York City, where he lives with his wife Shahrzad. Sabet says his international work is partially about correcting misconceptions about U.S. policy, but also “advocates abroad [who] ask me to come to give a shot in the arm to their efforts.”

Through it all he’s prepping for 2016. At last count, there are more than a dozen legalization and medical marijuana initiatives being readied for state ballots next year. “Obviously, I think 2016 is important,” says Sabet. “If we can figure out the angles that are important and be smart about it and not shoot ourselves in the foot, as we often do, we have a shot.”

But even some of Project SAM’s staunchest supporters are starting to sound like they’re losing hope. “We are not as far as I would have expected us to be,” says Patrick Kennedy, the organization’s co-founder. “I am proud to be affiliated with Project SAM and doing what I can to help, but I am facing the same ambivalence and intransigence he is facing. It’s very disheartening.”

But Sabet, for one, won’t be giving up the fight. He’s a “happy warrior,” says Kennedy.

It’s like he’s back on the tennis court, begging his opponents to underestimate him, hoping to thrive when all hope seems lost. He’ll keep fighting to the end – even if he’s all alone. “This is deep in my veins,” says Sabet. “I feel like it is my calling.”

At one during Sabet’s D.C. junket, his packed schedule risks getting the best of him. He’s slated to appear on what he believes is a taped BBC News segment, but the car service that’s taking him, Zinsmeister and Jones to the television studio gets snarled in beltway gridlock. While they’re still several blocks away, Sabet gets a call from the studio: The segment is live, not taped, and cameras are rolling in just a few minutes.

The three scramble out of the car and take off. Zinsmeister and Jones look stressed, but not Sabet. Running down the sidewalk, he’s grinning, like he’s having the time of his life.

“We’re running out of time,” he says. “It’s a good analogy.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.