Kodak’s Rebellious Offspring Wants To Cut Through The Social Media Clutter In The Age Of Instagram

AUSTIN, Texas — Imagine how much free time companies would have on their hands if they didn’t have to worry about capturing the attention of millennials. One would not expect that to be a concern for a brand that trades in personal photos, as today’s young people typically have more pictures on their iPhones than they know what to do with. But getting them to print those photos is another story.

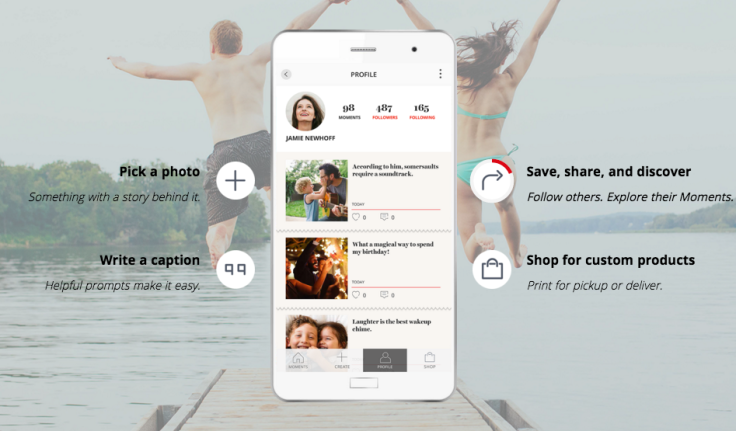

Kodak Alaris wants to change that with the help of the iconic, if creaky, Kodak brand. The digital imaging company, which spun off from the embattled Eastman Kodak Company in 2013, is seeking to reinvent the brand in the age of Instagram with its newly revamped Kodak Moments app. Announced Friday at the South by Southwest interactive conference here, the app lets users visually enhance their photos with text, layout and editing tools.

And this being 2016, it includes a social platform as well.

The idea, according to David Newhoff, Kodak Alaris’ vice president of mobile, is to harness social media to encourage consumers to print their photos more frequently. “Customers who print photos print about four times a year,” Newhoff told International Business Times. “What we’re trying to do is increase that ten- or twelvefold, which means getting someone to start using the app every month, and eventually every day.”

An obvious question is whether the world really needs another photo-sharing platform. Newhoff said Kodak Alaris is not trying to compete with the likes of Facebook or Instagram, but rather “play alongside them.” And, he said, it can offer something that the bigger social media players can’t — namely, a platform that is not dependent on intrusive advertising and data mining.

“Instagram is not doing a great job of providing a safe place for your storytelling,” Newhoff said. “They show you ads based on the data that they read from your photos, and they also are providing a platform that surrounds your photos with a lot of clutter and noise.”

Newhoff cited a company survey of 760 U.S. social media users in which 65 percent said they viewed social media as “superficial,” and of course the visual pollution of major social networks — particularly in an election year — is enough to scare anyone off.

Kodak Alaris can cut through the noise, Newhoff said. The company makes money through its digital imaging business, including the photo printing kiosks found at big-box retailers like Target. It can monetize the app by encouraging users to print more photos, either individually or as part of photo books and other products.

Born from the ashes of the Eastman Kodak bankruptcy, Kodak Alaris is a completely separate company owned by the U.K. Kodak Pension Fund, a trust that pays pension benefits to Kodak employees in Britain. Eastman Kodak, by contrast to Kodak Alaris, is largely focused on business-to-business endeavors like graphic arts printing, although the company still has its share of fun, including launching a retro Super 8 film camera at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas earlier this year.

As a brand, the name Kodak carries considerable industrial-age baggage. (Its hometown of Rochester, New York, is the epitome of a depressed factory town.) But Nicki Zongrone, president of consumer imaging for Kodak Alaris, insists the name is still “a big asset,” instantly recognizable to consumers around the world. The challenge, she said, is bridging Kodak with consumer habits of the 21st century.

“We’re creating something that is not just your father’s prints from film,” Zongrone said. “A Kodak moment is more of an emotional experience.”

Kodak Alaris announced the new Moments app in typical SXSW fashion, unveiling a “Memory Observatory” art installation at the Austin Convention Center. Visitors pass through a dimly lit portal — complete with psychedelic music and bubble-shaped chairs — and share their photos and memories. Those photos and memories are then shown back to them in a multi-sensory media projection. For context, it’s a bit like being in a rave “chill room” circa 1994, which is to say it’s about the most relaxing thing you can do at SXSW this year. The installation was directed by multimedia artist Marcos Lutyens.

It remains to be seen if any of this will enthrall those ever-elusive, ever-fickle millennials, consumers born approximately between 1981 and 1997. But the potential purchasing power of this sizable demographic cohort makes them impossible to ignore. And after all, they won’t stay young forever.

“What we’re really trying to do is get into their lives a little bit earlier from a digital point of view,” Newhoff said. “A lot of college students want to print to decorate their walls, and then the minute they get married and have kids, their printing activity around their photos goes through the roof.”

Christopher Zara covers media and culture. News tips? Email me. Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.