The Law Of Jante: How A Swedish Cultural Principle Drives Ikea, Ericsson And Volvo, And Beat The Financial Crisis

Swedish artist Linnea Gad sits perched on the edge of her plain white couch, leaning forward tentatively as she talks about a subject close to her heart: how cautious, even reticent, her countrymen are by nature, which has influenced her personal career as well as the nation as a whole.

“It’s interesting that you look at it in a positive sense -- how it may have saved Sweden,” she says. She takes a sip of her Swedish detox tea from a simple white mug, looks thoughtfully at the intricate parquet flooring, carefully considering a rarely discussed concept that she knows is difficult for Americans to understand.

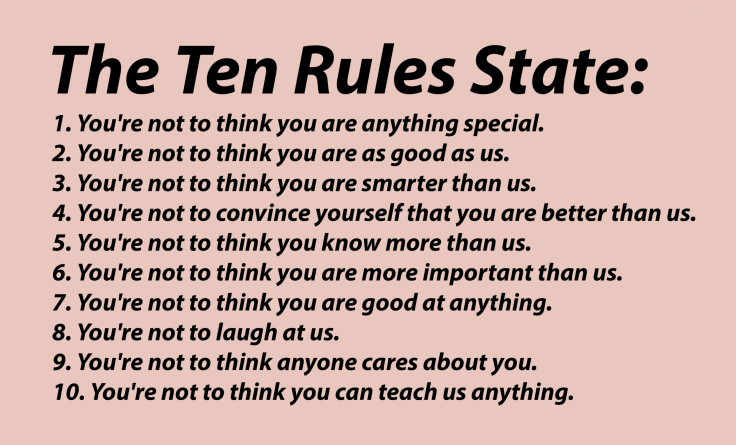

Even its name -- the Law of Jante -- sounds strange and esoteric. It embodies a cultural concept unique to Scandinavia, which essentially means: “You are not to think you’re anyone special or that you’re better than us,” with “us” meaning the collective population.

Those who are familiar with the concept often use the Law of Jante to explain the pattern of group behavior within Scandinavian communities that eschews overt self-promotion and achievement as unworthy and inappropriate. Beyond that, it has engendered in Scandinavian society a sense of humility and a respect for moderation that has profoundly affected the way people operate financially, where it’s better to limit risk and certainly not to focus openly on personal gain, both of which are, by contrast, mainstays of the American way of life.

The language of the rules sound oddly defensive in translation, considering that the Law of Jante is viewed primarily as a self-monitoring tool. But that is partly attributable to the fact that boasting, self-promotion and the like were considered distasteful, even rude, when it was developed about 80 years ago. There is also the matter of the inexactitude of English translation and the now-archaic linguistic tenor of 1930s Sweden. In any event, here is how the rules translate:

Some see the mindset embodied in the Law of Jante as a barrier to entrepreneurial and national economic success, while others see it as a tool that has hedged Scandinavians against failure, preventing them from taking the same economic risks that led much of the Western world to the brink of financial apocalypse beginning in 2008. There was no housing bubble in Sweden, in part because it would seem antithetical for anyone to take on more debt than necessary for essential living, where the chief consideration when contemplating a housing upgrade would be not “How much will the bank lend me?” but “Is an extra bedroom really necessary?” (Of course, Sweden had its own major financial crisis in the early 1990s. But the country got out of it by making the banks pay mightily for their overindulgence and for any bailout money they received from the government. In the end, the Swedish taxpayer lost nothing and the economy rebounded quickly).

While it may have always existed in Scandinavian countries, the governing principles of the Jante mindset were first verbalized by novelist Aksel Sandemose in his 1933 book “En Fyktning Krysser Sitt Spor” (“A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks”), where he described it as an involuntary subjugation of an individual’s aspirations and personal development. Jante itself is a fictional town that Sandemose based on where he grew up.

Eight decades later, the concept of Jante still rings true in Swedish society.

Gad, a Stockholm native who cautiously concedes that she emigrated to the U.S. four years ago to escape her own country’s constraints, recently returned to her adopted New York home from a visit to family in Sweden. She says the concept of Jante has made her think deeply about herself as an aspiring artist living in America, where self-promotion, networking and talking yourself up to others is an important part of getting ahead in a competitive world.

“I think there are a lot of artists in Sweden that never get noticed because they don’t dare promote themselves,” Gad says. “But by working at a gallery for two and a half years, I’ve noticed that you can’t force yourself on people -- they have to find you. So it’s a strange line that I try to balance. That’s why New York is good for art because it’s a networking community. People are constantly helping each other out and are really open to other people.”

While back in Sweden over the summer, Gad arranged to meet with a Stockholm artist to get advice and guidance on how to take her career forward. “She’s a great sculptor in Stockholm, and she is represented by a major gallery, but she was so shocked that I emailed her and asked to meet up,” Gad says of the artist. “She was shocked because no one does that, and she said it was very brave of me.”

The art world provides other anecdotal evidence of the personal, professional and economic power of Jante. Native abstract artist Hilma Af Klint, one of the first women to study at the Royal Academy of Art in Stockholm in the 1880s, was a pioneer in many ways, helping break down gender barriers in a country that was at the forefront of equality (some say as a direct result of the Jante concept’s socialistic backbone and equality-driven worldview).

Alhough Klint was relatively successful in the field of naturalism, the death of her younger sister years before she attended art school sent her down a more spiritual path toward abstract art. Unfortunately for her contemporary world, Klint was told in her mid-20s that her work would never be fully understood in her lifetime or for at least 20 years afterward. Many young people today might defy such negative messages, but Klint took it to heart and subsequently never showed her work to anyone, and she even stated in her will that she didn’t want her extensive body of abstract work shown to anyone. She died in 1944, leaving behind more than a thousand pieces of stunning abstract art. In 1970, her work was offered to the Moderna Museum in Stockholm, which declined the donation. It would be another 14 years before her art found a broader and ultimately international audience, first in Helsinki and then in Los Angeles in 1986 -- 96 years after Klint produced her first abstract work.

Some would argue that such self-limitation has suppressed entrepreneurialism and Sweden’s global business reach, but this argument would ignore the success of companies such as the privately held Ikea, the home-furnishings retailer, and Tetra Laval International SA, parent of the packaging maker Tetra Pak; clothier H&M Hennes & Mauritz AB (STO:HM-B); diversified manufacturer Saab AB (STO:SAAB-B), discounting its automotive failures, which pale in comparison with its success in other fields, such as jet engines; appliance maker Electrolux AB (OTCMKTS:ELUXY); and telecommunications-technology titan Ericsson (NASDAQ:ERIC). Each in its own way, these companies have provided functional, safe, unambitious -- but reliable and timeless products. They offer quality at the right price points: less flash and more craft.

In a broader sense, the Jante mindset has had a stabilizing influence on Scandinavian society and personal finance -- and, by proxy, has allowed Scandinavians to live relatively carefree lives characterized by realistic expectations and undergirded by collective social responsibility. And Scandinavia did not go completely unscathed by the financial meltdown that began in 2007, because financial markets around the world are inextricably linked. For examples, in Sweden, HQ Bank, the country’s largest investment bank, went bankrupt, and in Denmark, Roskilde Bank suffered the same fate amid allegations of fraud, and was the first Danish bank to be nationalized since 1928. But the losses were inconsequential to the wider economy. Scandinavia soldiered on, largely unperturbed, as nearly all of Europe and the U.S. suffered a far greater financial crisis brought on by excessive borrowing and risk-taking by households and banks that led to systemic breaches in accountability and ethics at all levels.

Verne Moberg, professor of Swedish and Scandinavian literature and culture at Columbia University, says that the Law of Jante does trickle down through society and can easily affect people and their positions at work: “Let’s remember, Sweden was against joining the euro and was very slow in jumping on the [European Union] bandwagon. But, yes, I do think there are interesting connections that can be drawn between business and the Jante law ethos in Sweden.”

The American Dream

For Gad, America offered a different allure, although she remains circumspect about embracing it. She is participating in the American Dream, doing things she never thought possible before -- having her own exhibitions and meeting people who might have seemed beyond reach before. “People move in out of their comfort zones, and there is a lot of opportunities ... sprung from the risk professional people take. As a young artist, it is definitely great to be in an environment where less calculated situations arise,” she says.

But, true to form, her approach is hardly one of abandon. Even in the rarefied professional atmosphere of New York, she is exceedingly careful.

“It’s always in my calculations,” Gad says. “You know, if I can’t get that job or that scholarship, I could always go back to Sweden because you know you’ll be taken care of there. I’ve never lived with the fear that if I get sick no one will take care of me.”

In the States, the financial collapse could be traced back to the mass pursuit of the American Dream. People in the U.S. talk about success in terms of “make or break” and “win or lose,” as if there were no alternative. It’s no coincidence that a game tie or draw doesn’t exist in American sports. It appears this type of mentality was once pivotal in making America through the risks of capitalism, but now seems to be breaking the middle class and poor. For Americans, it’s not just OK to have enough: Unlike in Sweden, most people in the U.S. want more than they need, which has created a nation of achievers -- and overreachers.

The American banking system felt the downside -- the nonreality -- of the dream as the housing market, stuffed full of billions, or trillions, of dollars of toxic assets, caused banks to collapse. Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. went first, Bear Stearns Cos. Inc. was salvaged by JPMorgan Chase & Co. (NYSE:JPM), and Merrill Lynch narrowly avoided the same fate of Lehman, as the Bank of America Corp. (NYSE:BAC) saved it at the last minute. All the major banks accepted an injection of cash from the U.S. Federal Reserve to keep them afloat, even though some didn’t need it.

While Jante still permeates Scandinavian society, modern Sweden is moving inexorably toward self-service and capitalism. A lot has changed from the days when a central business -- normally a factory in a town -- created most of the jobs and wealth, creating the perfect environment for Jante to exist. Today, there is a far less extreme version of Jante at work that enables a different sociological approach. Known as lagom, it reinforces the idea of useful limitation, yet expands the limits themselves, acknowledging both Sweden’s stabilizing influences and the economic potential inherent in its current stability.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, global companies based in Sweden tend to be painted in 50 shades of Jante. For examples, Ikea and H&M respectively offer simple furniture and clothing for “the people” at cheap prices that remain in line with the ethos of attractive ordinariness. Both companies are huge capitalist success stories, though, belying the stereotype that Sweden is Europe’s chief welfare state, where exorbitant taxes and government regulation stifle enterprise and financial achievement. In addition, Sweden is now home to some of the most important startup companies on the Web today: Music-streaming site Spotify AB, mobile-payments service Klarna AB and game maker Mojang AB. In addition, the country spawned the voice-over-Internet Protocol firm Skype, a unit of the Microsoft Corp. (NASDAQ:MSFT), and the database-management system provider MySQL, a unit of the Oracle Corp. (NYSE:ORCL).

While all these businesses have been successful, Swedes might look askance at both proclaiming that and overstating its importance. After all, overemphasis on economic potential carries the potential to undermine the public good, and it directly contributed to the housing bubble that destroyed banks, mired economies and generally ruined people’s lives. Yet it would be unwise to attempt taking full advantage of the resulting opportunities that come from having avoided such a fate. From the vantage point of Jante or lagom, unbridled opportunity tends to minimize the roles of personal and social responsibility. The question “Is that necessary?” is always being asked.

Lagom promotes a sort of glasnost version of Jante, the latter of which is now considered a bit antiquated and oppressive by some. Yet the basic rules are still deeply entrenched in humility and moderation, with the concept of “just enough” comparable with the idiom “less is more.”

Gad finds herself at a strange crossroads in life, almost a paradox of sorts. In an odd way, the culture that she was so keen to escape has created a license for her to go out into the world and put it all on the line if she wants, because should her version of the American Dream all come crashing down, she can always go home and be thankful for the law of Jante. But there she is in New York, determined to find an audience for her work, and meanwhile a bit nervous in a Jantean way about being featured in an article in the International Business Times.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.