In Los Angeles, Architects Find That Disadvantaged People Like Nice Buildings, Too

When Los Angeles architect Sonny Ward approached the directors of a feminist retreat in rural Mississippi about building a cardboard cabin for them, the women were initially not amused. “They were like, ‘Who are you and why are you coming here?’” Ward told the International Business Times from his office in L.A.

The retreat, known as Camp Sister Spirit, catered to feminists, lesbians and survivors of domestic abuse. Located in one of the most conservative states in the Bible belt, it had faced its share of controversy -- some of the neighboring landowners were hostile, to the point that the FBI and the U.S. Justice Department investigated claims of harassment in the mid-1990s (although no charges were filed). Unsurprisingly, the retreat’s members had learned to be a bit defensive. Also: A cardboard house?

Yet the idea made perfect sense to Ward, who grew up in Mississippi and, in addition to operating his own architecture business in West Hollywood, now teaches architecture at Woodbury University in Burbank, Calif. Ward has a strong sense of social responsibility, and believes architecture should reflect the identity of its inhabitants and contribute to their enjoyment of life, regardless of their financial status or access to power. “It’s not enough just to be excited by design,” he said. “You need to take into account the social and cultural aspect of a structure -- the story of the building.”

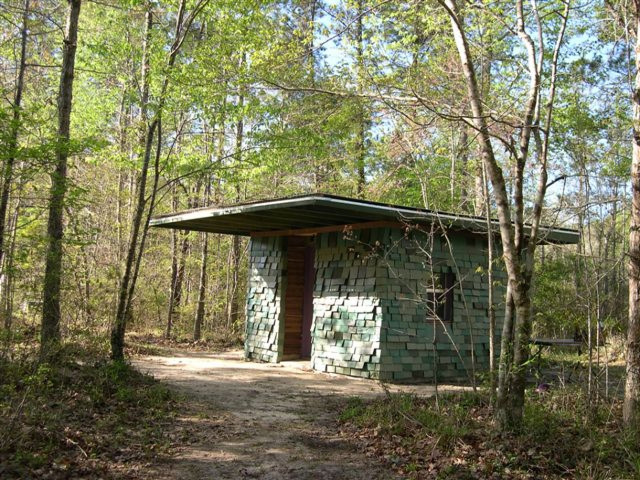

Completed in 2003, the cardboard cabin at Camp Sister Spirit was destined to have a memorable story, and eventually became a rallying point for the women, who had previously relied on prefabricated toolsheds for bunkhouses. The idea itself had a certain allure: It embraced the group’s outsider status through the use of cast-off materials -- the cardboard had been discarded by stores and destined for landfills. Plus, the cabin was cheap, built with a $3,000 grant from the Arcus Foundation administered by the University of California at Berkeley. Its walls were made of stacked and compressed cardboard linked by threaded steel rods and plywood plates that ensured structural integrity, then sided with cardboard shingles dipped in latex paint for weatherproofing. The result was functional, beguiling and strong: It survived the winds of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

After working on the Mississippi project, Ward continued to explore ways to apply architecture to social service when he began teaching at Woodbury and working with Jeanine Centuori, chair of the university’s undergraduate architecture program and director of the Woodbury Architecture + Civic Engagement Center, which grew from a program she founded in 2000. ACE, as the center is known, is funded by the university and grants from clients. It seeks to connect architecture students with social- and environmental-justice causes outside the classroom, mostly by designing structures for marginalized people or groups and social-service organizations, such as housing for the homeless on L.A.’s Skid Row.

ACE’s first project, which Centuori and Ward worked on together, focused on creating public uses of marginal spaces in urban neighborhoods. After that, the center undertook the design of a school in Chad for refugees from Darfur, where the Sudanese government backed a genocide of African villagers. The school’s design won several awards, but, because of coordination problems, the structure was never built, Centuori said. At that point, “Sonny and I realized that there were many good causes right in our own backyard of Los Angeles, and that our students needed to benefit from those direct experiences,” she said.

The university’s social-service program requires students to become involved in the community where they do their work. As for who benefits, “We cast a large net that is fueled largely by word of mouth,” Centuori said. “We look for social and environmental causes that are off the beaten path. ... We look for sites and organizations where there is the potential for architecture to make a difference to the well-being of the organization.”

She observed: “Architectural school is academic -- it’s about high-tech manipulation of form, [and] large things like museums and airports. This is the opposite end of the spectrum.”

Each semester, a group of 20 or so Woodbury students work with the ACE program on projects that help communities “in a tangible way,” Centuori said, and the students benefit from immersing themselves in the lives of the people who will use the buildings they design. “It’s like a barn-raising,” she said. “There’s a sense of collaboration.”

Last spring, the students completed a program that focused on the creative use of “materials at hand” -- an old architectural disclaimer that refers to construction materials that may not be perfect but are used of necessity. Scrounging together funding from the university, the nonprofits they work with, outside grants and the building-supply firms Lowe’s Cos. Inc. (NYSE:LOW) and The Home Depot Inc. (NYSE:HD), the students transformed 10 small Lowe’s storage sheds into multiuse structures for the Shadow Hills Riding Club, which operates a nonprofit equine-assisted therapy program for autistic children, paraplegics and veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. The budget was $1,500 per building. The buildings are now used for sleepover cabins that double as other functional spaces, including a library, kitchen, therapy space and relaxation area, with decks for bird-watching, sunning and performance stages.

The Woodbury students were required to transform the sheds so that they had natural light, ventilation, insulation and sleeping space for two, with each team using a specific building material: plastic, wood or paper. The plastic team ironed 2,000 ribbed polyethylene bottles donated by a recycling center and attached them to a wood grid, which at a distance made the house look like it had been attacked by tinsel, as noted by the Los Angeles Times. The wall design served more than a visual purpose: Gaps between the bottles and the shed allowed the structure to breathe. The students succeeded in taking small, everyday structures and adapting them in special ways -- which matters to their temporary residents, all of whom grapple with some kind of personal challenge, Centuori said.

Architecture students are generally given theoretical projects, often located at distant locations, and told to come up with a design. In contrast, she said the Lowe’s sheds project was “about responding to a specific set of client needs, and building on that.”

This summer, the students embarked on their next project, with a nonprofit known as Taking the Reins, an after-school program described by KTLA 5 that offers horseback riding and gardening primarily to at-risk, low-income girls as a way to increase their confidence. Taking the Reins executive director Jane Haven said that in addition to learning to ride and care for horses, the program focuses on every aspect of growing and consuming produce -- “seed to skillet,” as she put it. As part of the project, Woodbury students have been designing and building structures associated with the girls’ vegetable gardens. They started with an open-air “lath-house,” so-named because it is sided with open lathing reminiscent of a wall being prepped for plastering, which is used for sprouting seeds. The students are also designing an outdoor kitchen, an outdoor eating area, a chicken coop and a produce store, the latter of which will enable the girls to sell their produce to the public. The project will eventually tie the equestrian and gardening compound to an economic revitalization effort along the Los Angeles River and with neighboring Griffith Park via a planned $5 million public pedestrian/equestrian bridge.

Among the girls who participate in Taking the Reins, Christine Gyouloglian wrote via email that her favorite part of the compound is the lath house, where diffused light and open ventilation are conducive to sprouting seedlings in small pots. Now a high-school senior, she participates in the after-school program and serves as a mentor to younger girls. She recalled, “I remember how scared I was to get on a horse when I first started, but now I can take the reins confidently and just ride on.” Likewise, she said, growing strawberries, peppers, garlic, oranges and other crops has taught her to focus on healthy nutrition, and the compound’s chickens and horses have proved therapeutic in their own ways.

“The ultimate goal is to get the girls who come through this program to emerge as leaders in their community and beyond,” said Taking the Reins program director Janiene Langford. Like many such nonprofit groups, Taking the Reins is perennially stressed for funds, she said, and it is considering selling its 1938 barn to become financially solvent (the organization is now raising funds for its structural program). For that reason, Woodbury’s contributions are particularly important, she said.

Among the girls aged 11 to 18 who participate in Taking the Reins, most live in a comparatively poor urban area called District 13, which has the city’s highest obesity rate and the lowest availability of fresh produce. Some are transgendered, and others have parents who have been incarcerated, Langford said. Those are precisely the kinds of people who rarely have routine access to inspiring architecture, Ward observed. At the other end of the spectrum are girls who participate in Taking the Reins from families that are middle to upper class, who own their own horses and want to get to know girls from different backgrounds. For all of them, the lath house serves as an attractive common space.

Woodbury’s social-service approach was inspired by Auburn University’s Rural Studio, which focuses on creating inspired, affordable housing and other buildings for the poor, mostly in rural Alabama, Centuori said. The Rural Studio, the brainchild of the now-deceased architect Samuel Mockbee, “has brought awareness to this genre of work, and has elevated the discussion among architectural academics and practitioners,” she said. “It has become the benchmark for socially motivated architecture in academia.”

And, she added, “More broadly, there is a movement in architectural circles about the merits of socially motivated design.” That movement was the focus of a Museum of Modern Art exhibition in New York called “Small Scale, Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement.”

Ward described the Woodbury program as “a quicker, grittier, lower-budget urban version” of the Rural Studio, and noted that “there is a shift towards this [approach] across the country.” The Tulane University school of architecture in New Orleans developed just such a program after Katrina, which also sparked actor Brad Pitt’s Make It Right foundation, a charity that builds architecturally interesting, environmentally sensible homes for people in the city’s impoverished Lower Ninth Ward.

In creating what would become the template for the kind of work that Ward, Centuori and their students are now engaged in, Mockbee co-founded the Rural Studio in 1992 with a longtime friend and colleague, D.K. Ruth, with the avowed purpose of enabling his students “to step across the threshold of misconceived opinions and to design/build with a ‘moral sense’ of service to a community.”

Mockbee added before his death a dozen years ago, “It is my hope that the experience will help the student of architecture to be more sensitive to the power and promise of what they do, to be more concerned with the good effects of architecture than with ‘good intentions.’”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.