Mandela And The Dictators: A Freedom Fighter With A Complicated Past

ANALYSIS

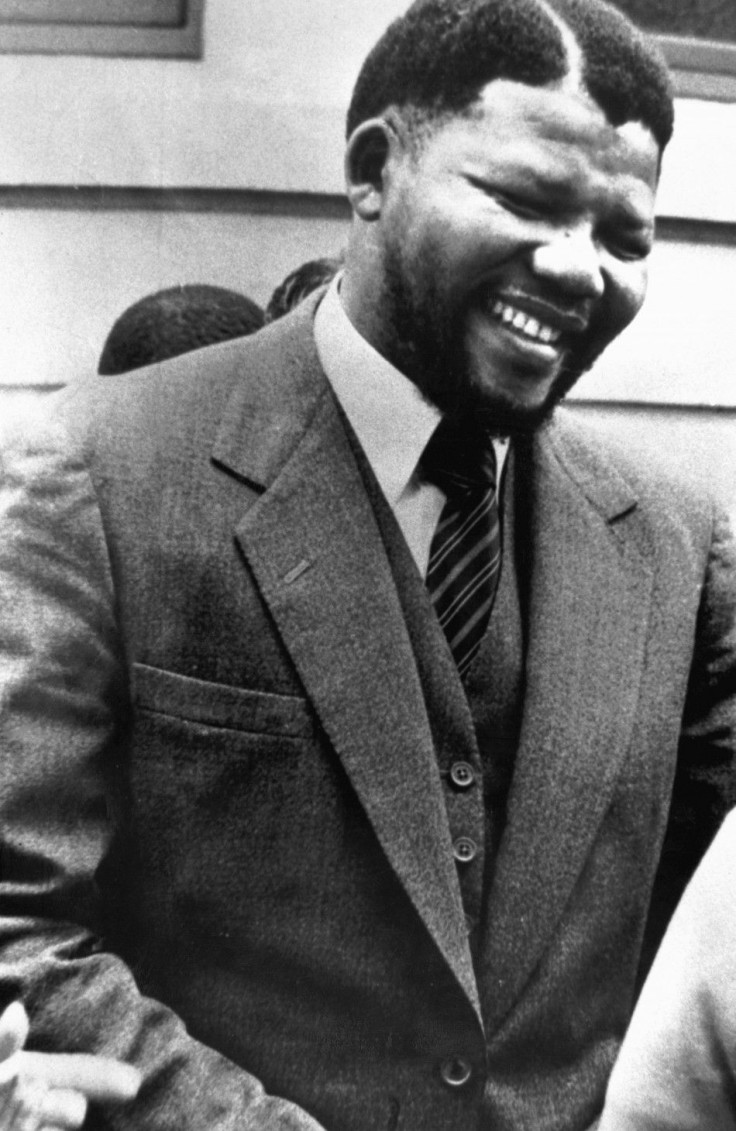

Nelson Mandela turns 94 on Wednesday, and all of South Africa is singing in his honor.

Over 12 million people joined together for an 8 a.m. birthday song, according to the Daily Telegraph newspaper of Britain. Children at school, commuters in transit, and men and women at work all raised their voices simultaneously to pay tribute to the man who helped end the era of apartheid in South Africa.

Mandela is physically frail today, but his legacy as the liberator of his country remains as strong as ever. He is seen as a hero, not only in South Africa but all around the world.

But Mandela's struggles were not as straightforward as they might seem.

Apartheid-era South Africa was a complex environment, requiring complicated calculations. Pro- and anti-apartheid camps were riven by internal disputes even as they battled fiercely against each other. Across the continent, myriad countries were going through their own growing pains as they ousted leaders and experimented with new governments. And all of these clashes were further politicized by the shifting alliances and animosities in the outside world, which was engulfed in a Cold War square-off during most of South Africa's apartheid struggle.

Considering the challenges, Mandela's achievements were monumental. But some of his tactics and alliances were more questionable than others, and his path to prominence was not without controversy.

Long Time Coming

The Dutch colonized the land now called South Africa beginning in the 17th century -- they eventually implemented societal segregation that ultimately marginalized the black population. The practice was written into legislation in 1948, when Mandela was 30 years old.

By that time, an illegal political group called the African National Congress (ANC) had already sprung up to mount a resistance to white rule over the majority black population.

Mandela joined the ANC in 1944, and formed the ANC Youth League shortly thereafter with the goal of promoting activism within the party. The next 15 years saw an escalating struggle between the apartheid government and black activists in South Africa; Mandela was banned, arrested, and tried by South African authorities.

These experiences changed his tactics, which had hitherto been based on peaceful, passive resistance. Now, he considered violence to be a necessary part of a working strategy to end South Africa's systematic oppression.

And so Mandela went underground.

In his 1994 autobiography, called Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela describes the change.

I, who had never been a soldier, who had never fought in battle, who had never fired a gun at an enemy, had been given the task of starting an army. It would be a daunting task for a veteran general much less a military novice. The name of this new organization was Umkhonto we Sizwe (The Spear of the Nation) -- or MK for short. The symbol of the spear was chosen because with this simple weapon Africans had resisted the incursions of whites for centuries.

Government buildings and apartheid symbols were the intended targets of this new militant policy, not people. But it is clear that Mandela was convinced of the ultimate inefficacy of a purely peaceful movement, especially when faced with the violent repression of the apartheid government.

Only through hardship, sacrifice and militant action can freedom be won. The struggle is my life. I will continue fighting for freedom until the end of my days, he wrote in his autobiography.

Mandela was captured and sent to prison in 1962, where he would remain for almost three decades. MK became more violent in his absence, and Nelson's then-wife Winnie was implicated for her fiery invectives against the government and her connections to several brutal acts of aggression on behalf of the organization.

During the 1980s, things began to look up. ANC's battle against apartheid was taken up by the international community and Mandela began conducting meetings with South African government officials. It was a sign that Mandela once again embraced non-violent means as the best way forward. He was released from prison in 1990.

Apartheid finally saw its de facto end in 1994, when all South Africans were allowed to vote in national elections and Mandela became the country's first black president.

Strange Bedfellows?

Once in power, Mandela felt a kinship to other leaders of countries who were struggling to escape legacies of oppression and colonization -- especially those who had supported his struggle against the apartheid government. But this led to some alliances that came under scrutiny in later years.

Muammar Gaddafi, for instance, was friendly with Mandela. The late dictator of Libya is now known as an iron-fisted ruler and a brutal oppressor of dissent -- but that wasn't always the case.

Gaddafi was among the first to pledge support for black South Africans in their fight against apartheid. Furthermore, the Libyan ruler -- who seized power in a bloodless coup from the monarchy in 1969 and declared Libya a state for the masses -- had a reputation for defending the sovereignty of Africans.

His interventions often ended disastrously, as when he backed Charles Taylor (Liberia) and Foday Sankoh (Sierra Leone), both of whose forces committed atrocities in West Africa. And his own people ousted and killed him in a popular uprising in Libya last year.

But at one time, many saw Gaddafi as a staunch defender of African interests. He did preside over a period of economic growth in Libya, and he was a major backer of the African Union. For that, Mandela called Gaddafi his friend, brother and ally. The two men were often seen embracing at diplomatic encounters, or even holding hands.

Mandela also had close ties with Iran. That country had just overthrown its Western-backed Shah in a popular 1979 uprising, becoming a theocratic republic. In support of black South Africans' similar fight for autonomy, the new Iranian government imposed sanctions on South Africa that were only lifted in 1994, upon Mandela's election.

By that time, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani was the Iranian president, and Mandela touted their close relationship. Though Rafsanjani was not considered an oppressive dictator, he frequently ruffled Western feathers -- among other things, he was accused by then-U.S. President Bill Clinton of harboring terrorists on Iranian soil.

To this day, as the United States pushes other countries to impose strong sanctions against Iran, South Africa retains significant economic ties with the Islamic Republic,

Mandela was also allied to Fidel Castro, another figure who supported his anti-apartheid efforts early on. Castro, seen as a liberator by some but a dictator by most of the Western world, was friendly with Mandela even after Cuba had become a pariah state.

We admire the sacrifices of the Cuban people in maintaining their independence and sovereignty in the face of a vicious, imperialist-orchestrated campaign, Mandela said on a visit to Havana in 1991, according to the Los Angeles Times. We, too, want to control our own destiny.

Not So Black And White

Mandela's story echoes that of many other national heroes, like Myanmar's Aung San Suu Kyi, India's Mahatma Gandhi, or the Dalai Lama of Tibet: a formative youth, a long period of exile or imprisonment, a rise to prominence, a call for peace and reconciliation.

But no story is really as simple or predictable as that. Nelson Mandela -- one of the world's most revered living men --depended on some of the world's most vilified leaders in order to achieve great success on behalf of a marginalized people, even embracing violence as a way to effect change.

Ethical or not, it worked. South Africa today is the continent's largest economy, and the ANC continues to dominate national politics with each new democratic election. Mandela even won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993.

And the 'Father of South Africa' will celebrate those achievements. He looks back on his life with a pride tempered by the knowledge that there is still much to achieve.

I have walked that long road to freedom, he said in his autobiography. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.