Million Man March 20th Anniversary: National Rally Didn't Bring Much Economic Change For Black Men

Damond Haynes was one of the storied million black men who rallied on the National Mall in Washington two decades ago to pledge self-reliance and fidelity to family and community. His participation couldn’t have come at a more critical time in his young adult life, he said.

At 23, Haynes had just earned a bachelor’s degree in black studies from the State University of New York in New Paltz and landed his first job at a student loan servicing firm. His paycheck helped him rent the Dodge Neon coupe that he drove solo for 400 miles from Utica, New York, to Washington.

“Just having all the brothers together was a big deal,” said Haynes, now a 43-year-old educational consultant and father of two young daughters in Brooklyn, New York. “It was about us. It was one of those moments in life that inspired my work in the community.”

Twenty years after the so-called Million Man March urged African-American men to atone for their personal failures and take charge of their families, the message from march leaders has changed to one demanding justice from a government they claim has continued to let black men down. As the marchers reconvened on the National Mall Saturday, they faced a reality that economic and social progress for black men has been meager since the original gathering. But lately there has been more attention on the issues stunting progress for black men, and that’s a positive thing, Million Man March participants and experts said.

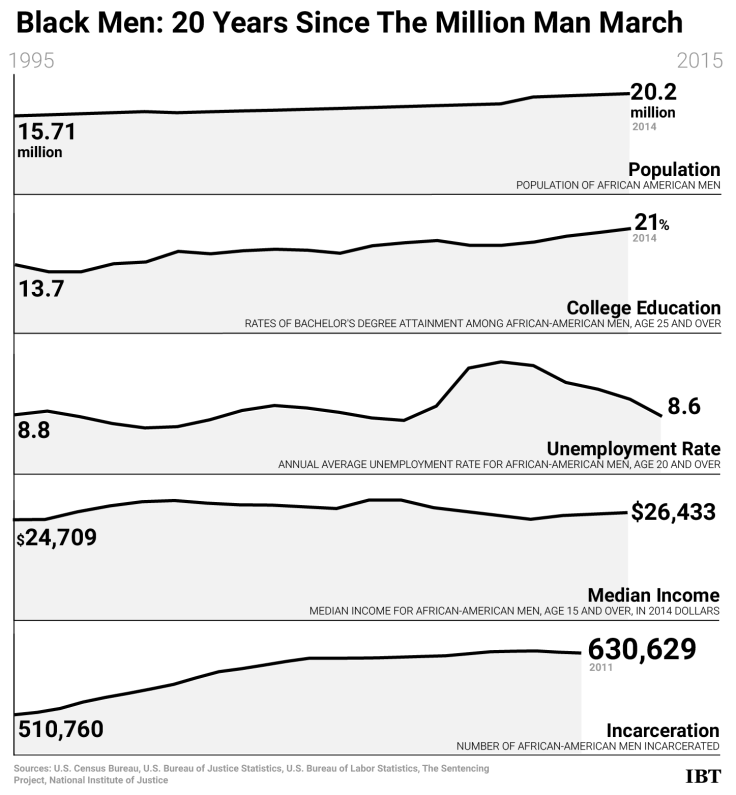

In 1995, black men were 15.7 million of the nation’s 266 million citizens, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Less than a quarter of them had attained college degrees and the median annual income was $14,982, or $24,709 when adjusted for inflation. The black male unemployment rate was as high as 10.8 percent, double the rate for white men. More than 510,000 were incarcerated, according to federal law enforcement data.

Twenty years later, black men are an estimated 20.2 million of the nation’s 318 million. A fifth of them hold college degrees, and the estimated median annual income is $26,433. Black men were unemployed at a rate of 9.9 percent in September, still double the rate for white men. Fewer black men are locked up in federal and state prisons than in 1995, but their rate of incarceration is six times the white male rate.

Black men were advancing as a demographic in the late 1990s, but momentum was halted by two recessions and inadequate economic recoveries over 15 years, said Valerie Wilson, director of the Program on Race, Ethnicity and the Economy at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington.

“I can think of three words to summarize any economic progress that black men have made over the last 20 years: brief, fleeting and uncertain,” she said. “Even the measurable improvements of the late 1990s can be called into question because of the distortions created by mass incarceration.”

Even if there have been only modest gains, history-making accomplishments of the past 20 years have given the appearance of great social progress for black men. Most notably, the election of President Barack Obama and the symbolism of an African-American family in the White House has inspired millions in the black community. Black men have served as heads of the U.S. departments of Justice and Education, two agencies critical to the enforcement of policies that shape the futures of black boys. In addition to billionaire and millionaire athletes and hip-hop artists, black men have become groundbreaking neurosurgeons and climate scientists.

Those achievements came during an expansion of the U.S. criminal justice system that took a disparate toll on black men. Police and vigilante killing of unarmed black men made headlines in the late 1990s. They continue to garner attention now, contributing to the growth of Black Lives Matter, a social justice movement started by grassroots activists in 2013. Black-white education and healthcare disparities also are dominant topics of black activism.

“I think there has at least been some very public attention on issues that will affect the future of black boys,” Wilson said. “But any real action has been limited, and we know that change happens very slowly.”

The black Muslim leader Louis Farrakhan, who organized the march with others, addressed the gathering's estimated at 837,000 attendees Oct. 16, 1995, although claims that the crowd was significantly larger or smaller have been advanced. “God is angry, America,” Farrakhan said to attendees from a sunlit stage on the West Lawn of the U.S. Capitol. “He's angry, but his mercy is still present,” he continued, according to a transcript of his keynote speech. “Brothers and sisters, look at the inflictions that have come upon us in the black community.”

But while he railed against the U.S. government, white supremacy and institutionalized racism, Farrakhan emphasized the need for black men to admit their personal failures and commit to curing afflictions such as absentee fathers, black-on-black violence and civic apathy.

“We've got to atone for all that we have done wrong,” he said. The atonement signaled that “you [have] tuned up your life, and now you're ready to make a new beginning,” Farrakhan added.

The march was widely viewed as successful. The Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. and former NAACP Chairman Ben Chavis were among speakers. But the event was not without some controversy. Several black Christian civil rights leaders and Jewish American leaders distanced themselves from the gathering because of Farrakhan, who had been labeled by the general public as anti-Semitic and racist. Black women were almost entirely left out of the Million Man March program, although hundreds of them rode on buses to support the men, according to participants. Some of the women cooked for male participants.

Erica Bailey was one of the women. As a sophomore English major at the historically black Hampton University in Virginia, Bailey took a bus to Washington and stayed with other young black women who wanted to witness what was considered the largest gathering for African-American men in history.

“There was this really great feeling that something great was going on,” said Bailey, now a 43-year-old attorney who lives right outside of Washington with her husband and their two young sons. But she wasn’t exactly inspired by Farrakhan’s keynote address. “I was hoping that his remarks were going to be more uplifting in the traditional sense,” Bailey said.

The Million Man March was reconvened to mark the 20th anniversary Saturday under the theme Justice Or Else. Organizers from the Nation of Islam, the black Muslim organization run by Farrakhan, called for the U.S. government to address long-held grievances by many minorities. “We want justice for blacks in America who have given America 460 years of sweat and blood to make her rich and powerful,” organizers stated on an event website. They also called for “an immediate end to police brutality and mob attacks,” as well as justice for Native Americans, Mexicans, the poor, the incarcerated and military veterans.

Bailey, who planned to attend Saturday’s event with her husband and sons, said speakers should set a tone that matches social justice activists' continuing call for an end to police brutality and more accountability in law enforcement. “I’m hoping that the speakers this time around can really get to the urgency of the issues,” she said. “Black Lives Matter is important.”

Haynes, the educational consultant in New York, said the persisting disparities for black men call for a more militant message at this year's event. "If things did get worse, the message needs to be harder," he said. "Atonement was about us. Now the message needs to be about [the system]."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.