More US Women Have Been Jobless For More Than Six Months Than In 2007; Overall The U.S. Has More Than Double The Long-Term Unemployed

It’s been over four and a half years since the official end of the longest period of economic contraction since the Great Depression, but there are still more long-term unemployed, job-seeking Americans than there were in 2007. And the situation is worse for women, according to a study released Wednesday from the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey Institute, which studies the effect of community development on vulnerable children, youth and families.

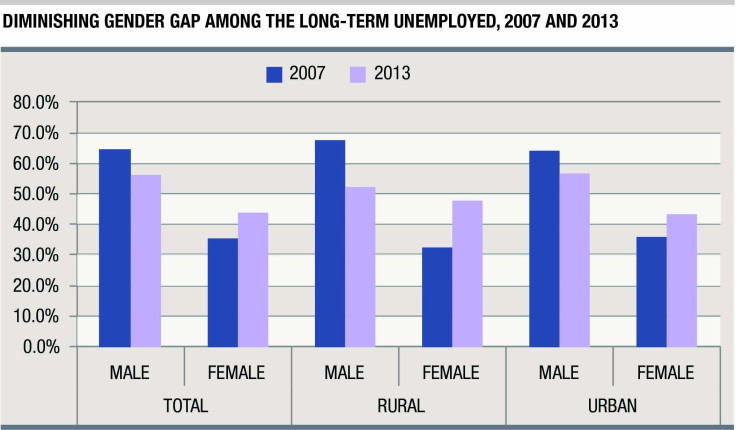

“We’re seeing a growing proportion of females among the long-term unemployed,” said Andrew Shaefer, doctoral candidate at the university’s Department of Sociology and author of the study, which analyzes data from the official Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau.

The problem of long-term unemployment is currently being debated in the Senate. Republicans have demanded that the $6.8 billion cost of further extending emergency unemployment benefits to 1.3 million Americans would have to be covered with cuts to other public spending programs.

Emergency jobless benefits have been extended 11 times since President George W. Bush first implemented them in 2008. Extended benefits are covered federally while standard jobless benefits are covered federally and with state and local contributions.

Overall, the percentage of long-term unemployed, defined as anyone who has been looking for work for at least six months, stood at 39 percent of all jobless, working-age Americans last year. That’s more than double the number of jobless in this category in 2007.

The so-called Great Recession began in December of that year and the data regarding the long-term unemployed suggest the effects of the economic downturn have not abated for the working and jobless poor.

The reason for that is debated largely along partisan and ideological lines – with the right saying welfare creates a culture of dependence on big government and inflates the national debt while the left says emergency jobless benefits are part of a larger social contract and a form of economic stimulus vital for U.S. job creation and recovery.

Regardless of the reasons for the problem or what to do about it, the numbers show more long-term unemployed, and that women are filling in the gap as men decline in this category.

In 2007, 35 percent of long-term unemployed were women; last year that figure stood at 44 percent. Part of that may have to do with married households where women filled in as breadwinners when their male spouses lost their jobs, and then they returned to homemaking as their husbands rejoined the workforce.

About 35 percent of the long-term unemployed are married with or without children. But Shaefer points out that 65 percent of the long-term jobless are single, albeit they may be living with and depending on partners they’re not married to.

A certain percentage, particularly younger working-age Americans, is likely living with or depending on their parents. About 20 percent of all long-term unemployed last year were between the ages of 16 and 24, according to the study.

Others have taken on jobs in the informal economy, especially in rural America. The statistics on the percentage of Americans working outside of proper tax-revenue collecting channels are hard to come by. A 2011 study by the Urban Institute estimated that between 3 percent to 40 percent of the U.S. labor force was working informally (meaning they are paid illegally in cash that goes unreported as income), but that’s a broad estimate that includes undocumented labor from illegal immigrants and white-collar crime that hides income from the government.

The U.S. has traditionally extended unemployment benefits during and in the wake of economic recessions, but this time it seems the wake of the recession has been larger than it’s ever been. Many of the long-term unemployed are still relying on emergency unemployment extensions to make ends meet because they’ve been jobless beyond the 26 weeks that most states provide for standard unemployment benefits. The Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program authorized by Congress in 2008 expired on Jan. 1 and the U.S. Senate is gridlocked on extending these benefits.

Critics have argued that the extensions themselves have exacerbated the situation by incentivizing the jobless to make lackluster efforts in seeking employment. In December the National Bureau of Economic Research released a paper suggesting that “during the Great Recession” the “unprecedented extensions of unemployment benefit eligibility” has exacerbated the problem of the long-term unemployed. The White House responded that not extending the benefits would adversely affect 1.3 million of the U.S. working poor and lower demand for goods they would otherwise purchase, costing 240,000 jobs in 2014.

Click here to read the full report in .pdf format from Carsey Institute.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.