NASA Releases New Cassini Findings About Saturn And Its Rings

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which was a part of the Saturn system for over 13 years, may have plunged to its death in the upper atmosphere of the gas giant, but the data it collected during its mission is still being analyzed by researchers back on Earth. At a news conference Monday, some members of the Cassini team presented new findings based on that data.

Saturn has 62 known moons, some of which orbit within the gaps of its rings. But those gaps are also home to a number of moonlets — small bodies, up to 500 meters in diameter. As they orbit the planet, they produce a similar phenomenon in the rings as newly forming young planets do in the dust ring around a star — they clear out space for themselves.

These ring features created in the wakes of the moonlets are called propellers, and six of them have been observed and tracked over the years by Cassini. Speaking at the conference at at the American Astronomical Society Division for Planetary Science meeting in Provo, Utah, Cassini participating scientist and imaging team associate Matt Tiscareno of SETI Institute in Mountain View, California, said that the researchers were surprised to find swarms of smaller propellers in the last images of the rings taken by Cassini a day before its mission ended.

Data obtained by the spacecraft also allowed scientists to update the theories to explain why Saturn’s rings don’t spread out and dissipate across the solar system. It’s been theorized that particles of the B ring — the third from the planet — is kept in place by the effect of gravity from Mimas, one of Saturn’s moons, on its outer edge. Similarly, the outer edges of the A ring — the outermost of the main rings — were thought to be confined by the gravitational pull from the moon Janus.

However, Cassini provided “high-resolution views of intricate waves in the rings, along with precise determinations of the masses of Saturn's moons” to scientists and their analysis showed that a large number of moons — Pan, Atlas, Prometheus, Pandora, Janus, Epimetheus and Mimas — combined to keep the A ring in its place. A study on the subject, led by Radwan Tajeddine of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, will be published Wednesday in the Astrophysical Journal, NASA said in a statement Monday.

Bulk of the rings is made up of water ice, but the researchers found traces of other unexpected ingredients that often rain down into the upper reaches of the planet’s atmosphere. For example, there was the presence of methane, which was unexpected in its abundance in both the rings and the upper atmosphere of Saturn.

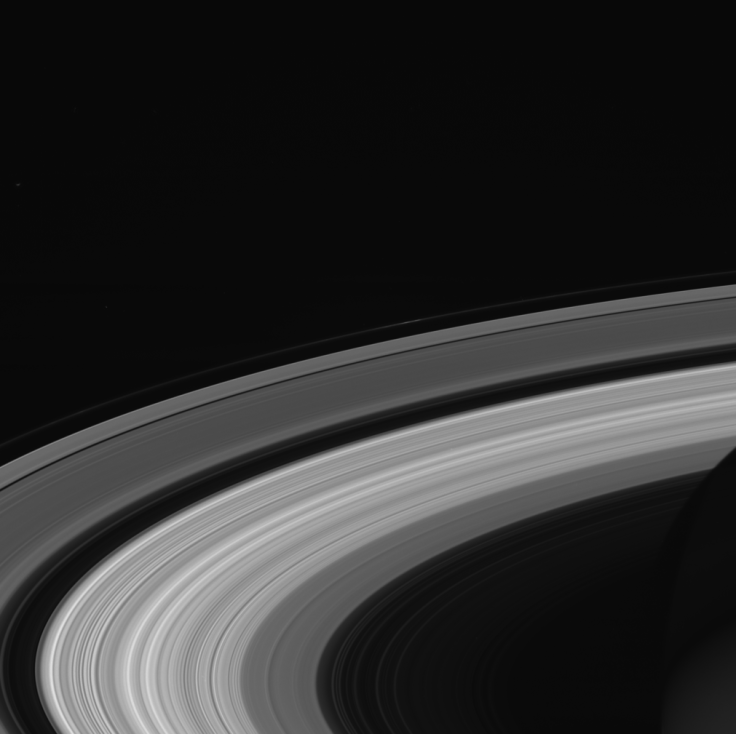

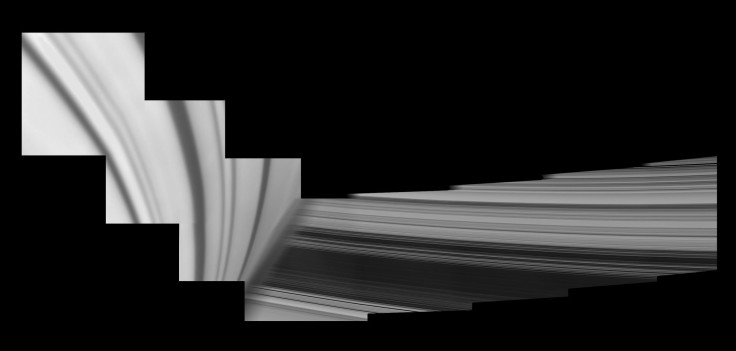

Two new images of the rings were also released, one that shows a panoramic view of the rings and another showing the rings behind Saturn, their shadows falling on the planet.

A short movie that shows auroras on Saturn in ultraviolet light, captured by Cassini’s Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrometer, was also released by the researchers.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.