Panama Canal Anniversary 2014: 100 Years Ago Today, Navigation Project Launched “American Century”

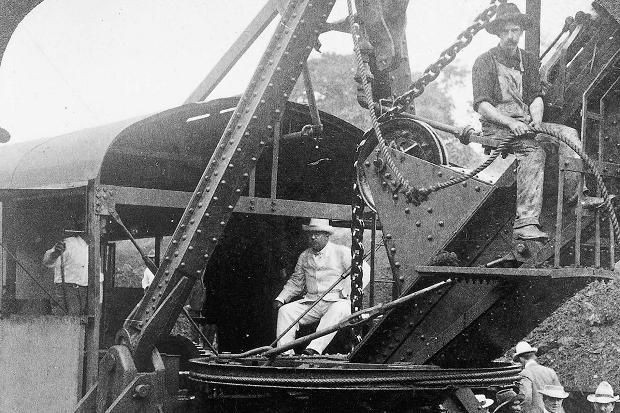

When President Teddy Roosevelt posed for the cameras astride a massive steam shovel during construction of the Panama Canal in 1906, it was more than a simple photo op. Though the scene was clearly staged, it symbolized a crucial moment in American history.

Building the canal, which opened 100 years ago on August 15 during Roosevelt's presidency, may not have been as outlandish as the century’s later big feat -- putting a man on the moon. Nor was it simply a grand and blatant exercise in nascent American power, as it is sometimes characterized. It was more a testament to advancing mechanical technology in the United States, and specifically, a proto-American machine capable of tearing the world apart, eight tons at a time: The steam shovel, which in many ways launched what came to be known as the American Century.

Winnowing the detritus of historical moments sometimes reveals one essential thing from which all else follows, such as gunpowder or the plow. In the case of the Panama Canal, that thing was the steam shovel. Completing the canal would ultimately require a rebel coup in Colombia, cost about US$375 million and lead to the deaths of tens of thousands of people. It would forever change the flow of traffic around the world, speed shipments and prevent untold numbers of shipwrecks in the vicinity of Cape Horn. And it would catapult the steam shovel to worldwide fame.

As the New York Times observed on Oct. 24, 1909, when canal construction was underway, “There is little of romance in the steam shovel, but its great part in the life of to-day none the less deserves recognition... The Panama Canal Job has recently thrown the American steam shovel in the limelight before the world." The Times noted that when the U.S. government first undertook to build the canal, which it described as "the task that had baffled the world’s engineers," the public was skeptical. Every previous effort had ended in failure. But the steam shovel enabled the U.S. to deliver the goods.

The idea for a connecting canal across the Isthmus of Panama had been bandied about for centuries, but until the U.S. undertook its effort the results had been uniformly disastrous, including the deaths of tens of thousands of workers, the bankrupting of companies and even one nation, the abandonment of miles of half-completed excavations, rusting stockpiles of machinery and acres of abandoned worker housing.

As early as 1625, Jesuit scholar Josephus Acostus had written of the canal idea being discussed at the time, “There is no humaine power able to beat and break down these strong and impenetrable mountains... Those who seek to build a canal should fear punishment from heaven, in seeking to correct the workes, which the creator by his great providence hath ordained.” Though there was plenty of punishing evidence from the past, the steam shovel dramatically changed the dynamic. Mountains could now be broken.

The steam shovel was an American invention that embodied the country's ethos at the beginning of the 20th century and facilitated its most stunning undertaking to date -- the excavation of an estimated 170 million cubic yards of rock and dirt over the course of a decade to link the Pacific and Atlantic oceans and, depending upon the points of origin and destination, shave from 8,000 to 12,000 miles off trans-ocean shipping routes.

The largest previous earthmoving project, the Suez Canal, built two decades before, had relied upon the backbreaking labor of thousands of men with shovels, and had mostly involved moving sand in flatlands. The massive amount of rock excavation necessary to link the Atlantic and Pacific via the 50-mile-wide Panamanian isthmus had stymied all previous efforts even though the passage was so narrow that both oceans could be viewed from one high hill.

Historically, maritime travelers had to pass around the entire mass of North and South America, including the bottom tip, the tempestuous Cape Horn, which was littered with shipwrecks. Various overland routes had been established across the isthmus over the centuries, usually incorporating partial passage along Panama's interior rivers and streams, culminating with a connecting railroad built by the U.S. in the 1850s that followed the same basic route later used for the canal.

The earliest recorded reference to a proposal to build a Panama canal dates to 1534, when Spain’s King Charles V ordered a survey in hopes of finding a better shipping route to the silver mines of Peru, on the Pacific side of South America. Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa had discovered the isthmus in 1503, and Charles V hoped to use it to gain a military and commercial advantage over Portugal, Spain’s biggest rival at the time. Spain’s Panamanian governor no doubt hated delivering the news to the king that the survey had indicated building a canal across the isthmus would be impossible. In the end, Spain had to satisfy itself with land routes -- the Camino Real and later, the Las Cruces trail.

More than a century after that, in 1698, when Spain’s control of the region was in doubt, the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and The Indies undertook construction of an improved overland trade route across the isthmus, but after two years that effort ended in failure, bankrupting the Scottish kingdom and indirectly forcing it to align itself with England and Wales under the auspices of the United Kingdom. The company’s founder, William Paterson, insisted that the route could also be used for a canal, but not surprisingly, considering the difficulties encountered in building an overland route, that idea went nowhere. Spain, which had blockaded Scotland’s efforts to found a colony in Panama, again proposed to build a canal there in 1819, but gave up due to a revolt among its South American colonies. In the 1820s and 1830s, Colombia, the U.S. and France all studied or proposed railroads across the isthmus, but none gained traction.

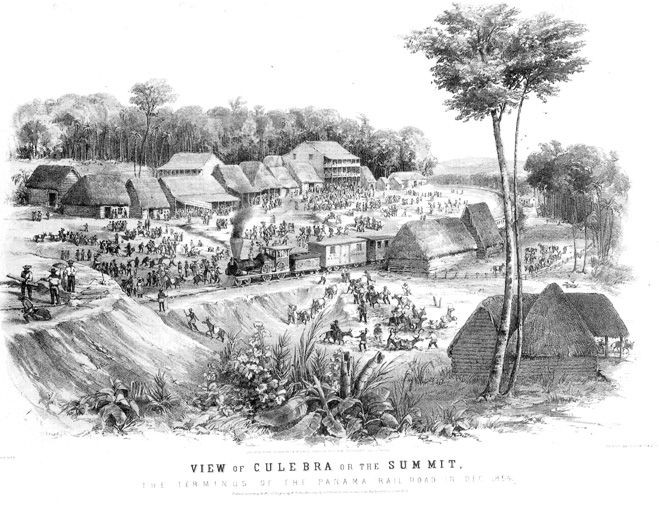

The idea of a better isthmus crossing again surfaced following the California gold rush of 1849, which greatly increased shipping traffic to the Pacific coast and inundated Panama with prospectors and others from Europe, Asia and the eastern U.S. seeking a shorter route to California. At that time, the only viable options available to those travelers was the months-long passage by ship around Cape Horn, a journey of similar duration -- and entirely different perils -- through the hostile territory along the Oregon Trail, or an isthmus crossing in part aboard small boats on the Chagres River and overland by mules for 20 miles along the old Spanish trails. In response to increased demand for a better crossing, U.S. businessman William H. Aspinwall, who operated Pacific mail packets, partnered with other businessmen in New York to create the Panama Rail Road Company, which raised US$1 million from the sale of stock and hired new engineering and route studies for a cross-isthmus line that was completed in 1855.

Building the railroad -- which is still in use -- was in many ways as challenging as building the canal would be 60 years later. The heaviest tasks were done by steam-driven pile drivers, tug boats and locomotives pulling cars loaded with excavation and fill material, with the remainder of the work done by multinational laborers using primitive tools. So many construction laborers died from yellow fever, malaria and cholera that at times construction ground to a halt, and a special cemetery train made daily runs. The railroad company kept no official count, but estimates of the total number of deaths range from 5,000 to 10,000. Many died with no known next of kin, and in a macabre decision, the company sold bodies to medical schools abroad as research cadavers, pickling them in barrels for shipment.

Building the railroad cost $8 million and required more than 300 bridges along its route as well as the excavation of a deep cut through the rocky continental divide. Once it was complete, ships were able to discharge and load cargo for transit across the isthmus at each terminus of the line. The railway also operated its own shipping line connecting with New York City and San Francisco and other ports in Central America. Two of the railroad company’s ships, the SS Cristobel and the SS Ancon, would be the first to officially transit the Panama Canal when it was completed in 1914.

Though the railroad provided a viable alternative to passage around Cape Horn -- reducing a journey by ship of up to six months to a few hours on a train, it did not negate the need for a canal. Partly it was a matter of scale: Trains could not compete with ships in terms of the volume of goods that could be moved, which meant that cargos had to be off-loaded at one terminus of the rail line -- a laborious, time-consuming, risky endeavor, then loaded onto what were likely multiple trains, hauled across the isthmus, unloaded from the train and loaded onto another ship on the other side. Even given the reduction in travel time, such a transit was extremely expensive, more suited for passengers than cargo. Most shippers continued to make the long voyage around the Cape.

So, as the railroad was facilitating its share of transcontinental traffic, the U.S. government was again pursuing plans for a canal, and commissioned a survey the year the rail line opened that was also published as a book, “The Practicality and Importance of a Ship Canal to Connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.” In 1869, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant – who had previously failed in an effort to change the course of the Mississippi River at Vicksburg by digging a canal during the American Civil War -- embraced the Panama Canal idea, and under his direction, the U.S. undertook negotiations with Colombia, which controlled the isthmus. Subsequent surveys concluded that a better route would go through Nicaragua, but at the time neither option was exercised.

In 1877, French engineers Armand Reclus and Lucien Napoléon Bonaparte Wyse published their own canal proposal, designed to build upon France’s construction of the Suez Canal, which was completed in 1869 (and which, like the Panama Canal, had a long pre-history, in its case dating to the pharaohs). In 1881, France proposed a sea-level Panama canal, without locks to raise and lower ships to accommodate changes in elevation, along the same basic route as the Panama Railroad. But owing to engineering problems and high worker mortality, the project went bankrupt and was abandoned in 1889 when it was about 50 percent complete. France had spent $287 million and an estimated 22,000 workers had died.

Though the steam shovel had by then been invented, it had limited capacity, able to move only about 25 percent of what later American equipment could handle -- a crucial difference when so much material had to be excavated and time was of the essence. In 1894, a second French company, the Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama, was created to maintain the existing works and equipment while a buyer for the canal project was sought, according to PBS’s American Experience: Panama Canal. The asking price was $109 million. One of the problems the French had encountered would likewise plague the Americans 25 years later – landslides that resulted from deep excavations of rugged terrain in the rain-soaked region.

In January 1903, representatives of the U.S. and Colombia signed a treaty granting the U.S. a lease on the canal route for $10 million, but the effort stalled when the U.S. Congress ratified the agreement but Colombia’s Senate did not. As an end-run, the U.S. lent its support to Panamanian separatist rebels in exchange for their support for construction of the canal. During the brief and successful uprising, U.S. warships blockaded Colombian troop movements and Panama declared its independence. The next day, the U.S. and Panama hastily signed a canal treaty.

The following year, the U.S. bought France’s rusting equipment and completed earthworks, as well as the privately owned Panama Railroad, at a total cost of $40 million. The U.S. also paid Panama $10 million (and in 1921, would pay Colombia an equal amount to recognize the treaty with Panama). A U.S. government commission, the Isthmian Canal Commission, was created to supervise construction and given control of the Panama Canal Zone.

In a sense, the American canal undertaking was pure Roosevelt -- forward-thinking, optimistic, confident and brutally destructive of whatever stood in its way. As Rose van Hardevald, the wife of a steam shovel engineer who worked on the canal recalled in David McCullough's "The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914," Roosevelt's bearing inspired confidence in everyone. Recalling her glimpse of the charistmatic president during his 1906 canal inspection trip, she said, "Mr. Roosevelt flashed us one of his well-known toothy smiles and waved his hat at the children. And I was more certain than ever that we ourselves would not leave until it [the canal] was finished." Two years before, the van Hardevalds had set off from their Wyoming home to Panama, confident of the project's completion because, she said, her husband insisted, "With Teddy Roosevelt, anything is possible."

Yet due to the cloud of past failures that hung over its long history, the canal project was not an easy sell. It needed someone like Roosevelt to get the support of Congress and a skeptical American public. Like the railroad, it would carry high human and material costs due to the tropical climate and rough terrain as well as the relative impunity with which workers were exploited. Canal laborers were rigidly segregated and worked and lived in vastly disparate conditions, for unequal pay, though all faced myriad dangers. During construction, an estimated 20,000 died from tropical diseases and from miscalculated explosions. There was also a strong imperial air about the American approach and its sponsoring of the uprising against Colombia -- an early example of gunboat diplomacy that the New York Evening Post at the time labeled a “vulgar and mercenary venture.”

But those aspects of the story received comparatively little attention at the time. What mattered most was that the U.S. had figured out how to impose its technological, financial and mechanical might on global commerce. Most of the world had a vested interest in the project's success, and aside from the government of Colombia, supported it.

The success of the canal effort was inextricably linked to America’s homegrown mechanical technology, and specifically the steam shovel, which had been invented and patented by Pennsylvania engineer William Otis (a cousin of Elisha Otis of elevator fame) in 1839 and improved upon over the decades, becoming larger, more powerful and better capable of operating in difficult environments. During the nation’s westward expansion in the mid- and late-19th century, the machines had been used extensively for mining and railroad construction, and once the U.S. embarked upon building the canal, the government ordered 102 of the steel behemoths from Ohio’s Marion Steam Shovel Company and Milwaukee’s Bucyrus Foundry and Manufacturing Company (Marion, Ohio, still bills itself as the “city that built the Panama Canal,” because both companies were founded there, though Bucyrus, which supplied 77 of the machines used for the historic dig, had by then moved, according to a U.S. military history of civil works).

The U.S. canal project is often seen as an outgrowth of emerging American power, and in many ways it was. The nation, which had recently flexed its muscles in the Spanish-American War that catapulted Roosevelt to the presidency, was at the forefront of industrial development and automotive, railroad and aeronautical technology, which meant that it was better positioned and equipped than any other nation to make the centuries-old dream a reality. The country was also in the early stages of major social change. It was a time when anything seemed possible.

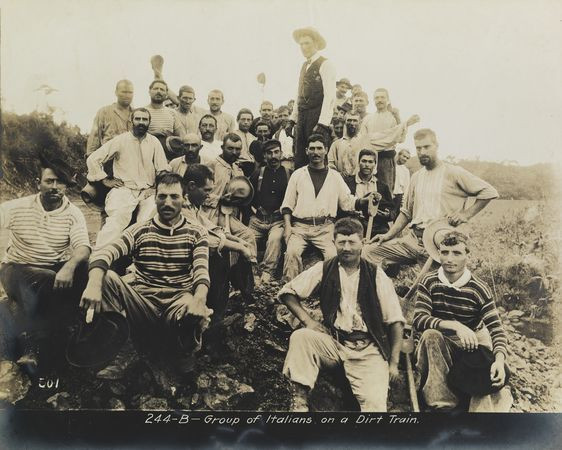

The year U.S. canal construction began, 1904, saw Florida promoters touting what would later be described as the first airline, using boat-planes to shuttle passengers between St. Petersburg and Tampa; Thomas Benoist, builder of the boat-planes, then predicted, "Some day people will be crossing oceans on airliners like they do on steamships today." Other areas of human endeavor that had previously seemed impenetrable were meanwhile being breeched: The suffrage movement was gaining traction in the U.S. and Europe, and trade unions were starting to take hold, to the chagrin of powerful corporate interests. For dreamers of grand engineering projects, the challenge of building the Panama Canal was irresistible, and the timing seemed right. If American workers were prone to unionize, there was an unlimited supply of easily exploited workers in the West Indies. All that was required was deepening and widening the basic route followed by the existing 48-mile Panama Railroad. What could be so hard?

For starters, the route passed through steep, rocky terrain, vast swamps and turbulent, floodprone rivers and streams, the majority of which was shrouded in malarial jungle. From the outset, keeping personnel was also a problem. Most of the workers were African Americans from the West Indies who lived in crude accommodations and did the worst jobs for less pay than their white counterparts. Such workers were less likely to push for higher pay or better work conditions, and when there was occasional unrest it was quickly quelled by railroad security and the Panamanian police. Strikes accomplished little because there was a vast pool of workers to draw from, so that even with widespread deaths and high employee turnover, there was rarely a shortage. Even a strike by highly-skilled steam-shovel operators failed to gain traction; the railroad company simply found other workers to take their place. The project employed about 45,000 people at the height of construction, including about 4,000 U.S. women who worked primarily as nurses and bookkeepers. The position of chief engineer, a presidential appointment, tended to be a revolving door as a result of complications ranging from tropical illness to mental fatigue.

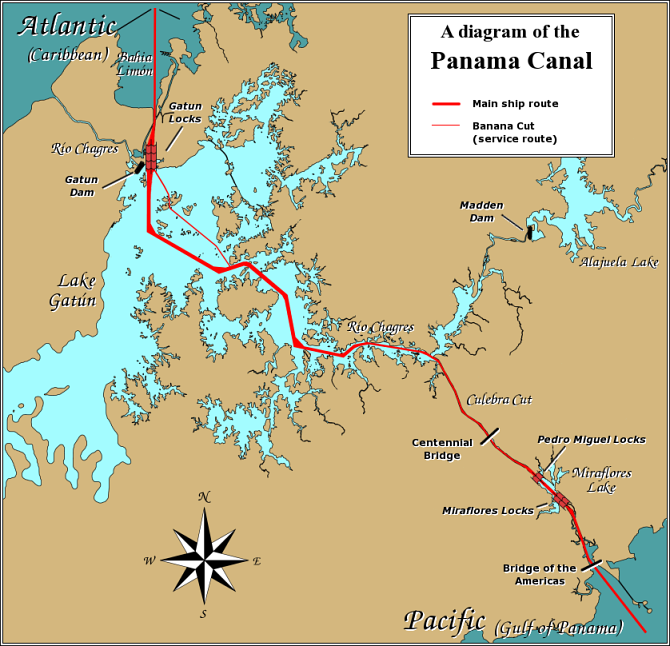

Remarkably, considering that the idea had been under review for so long, the canal’s design had still not been finalized in 1905, a year into construction. A U.S. engineering panel continued to recommend a sea-level canal. Later studies called for a canal and lock system to raise and lower ships the 85 feet between sea level and a manmade impoundment to be known as Gatun Lake, which, when built, would be the largest in the world. In time, the latter option was chosen.

In addition to the use of massive steam shovels, the American canal project included a major mosquito eradication program because the insect had by then been identified as the vector for malaria and yellow fever. The teams of men who continually sprayed swamps and waste areas with insecticides and oil to eliminate mosquito breeding grounds were crucial to the success of the U.S. effort.

The French had already excavated about 30 million cubic yards of soil and rock, which the U.S. augmented with its mammoth excavation machines and by implanting explosives as deep as 27 feet using pneumatic drills connected to compressor plants located miles away and blasting openings in the rock.

To accomplish the digging, 102 large, rail car-mounted steam shovels were brought in along with giant steam-powered cranes, hydraulic rock crushers, cement mixers and dredges, most of which represented new mechanical technology developed and built in the U.S., according to ConstructionEquipmentGuide.com. The existing railroad also had to be upgraded to accommodate heavier stock and in some cases elevated above Gatun Lake. Most of the excavated material was used to build the dam for the lake and for improving the railroad bed. When completed, the canal cost about $375 million and was the largest American engineering project to date.

The opening of the canal should have been a crowning moment for the U.S., yet the official day passed inauspiciously. War in Europe had broken out on July 28, 1914, and the day before the SS Ancon officially became the first ship to pass through the length of the canal, China declared war on Germany. As the UK’s Newcastle Journal reported on Aug. 18, 1914, “An event of world-wide interest took place on Saturday, but in the stress of the European war it has passed with nothing more than brief record… Reuter’s message states that the occasion, though regarded as a festival, was one of local celebration only. This gigantic engineering feat, accomplished after long years and under many adverse circumstances, will not secure the attention it deserves; yet the fact will not in the smallest degree affect the value of the enterprise to the world’s shipping. Of the comments of the Press in New York the most concise is that of The Globe, which remarks that by the opening of the Panama Canal, ‘8,000 miles of tedious seafaring around is cut to a ten-hour passage through a fifty-mile waterway.’”

In the coming decades traffic through the canal would grow steadily, from about 1,000 ships in 1914 to about 13,000 today, though the number has declined slightly due to the limits on the size of ships that can pass through. The canal is in the process of being widened, this time by Panama, which now controls the zone, but its monopoly is threatened by two decidedly 21st century factors: the melting polar ice caps, which enable ship traffic to pass through the Arctic Sea, and Nicaragua's awarding of a 50-year concession in 2013 to Hong Kong-based HKND Group to develop a canal through that country, following the route the U.S. originally preferred.

As for the machines that enabled the Panama Canal to be built, they continued to be used for mining, for digging the foundations of early skyscrapers, and, in the 1920s, for laying the groundwork for America's first major highway building program. But a decade later they were being replaced by more compact draglines with diesel engines that were cheaper and simpler to operate.

Today, the steam shovel's successors include monstrous earth-moving machines, one of which, known as Big Muskie, reportedly moved twice as much dirt as was excavated for the entire Panama Canal. But the steam shovels themselves, a century after their moment in the limelight, have long since been scrapped or relegated to museums.

Follow Alan Huffman on Twitter @alanhuffman1.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.