Paris ISIS Attacks: Tech Industry Says 'Anti-Terror' Back Doors Would Make US Less Safe

SAN FRANCISCO -- The Islamic State group’s deadly attacks in Paris have reignited a debate between Washington and Silicon Valley as some lawmakers push tech companies to create so-called back doors to their services that would allow law enforcement to break encryption in their efforts to identify and apprehend terrorists.

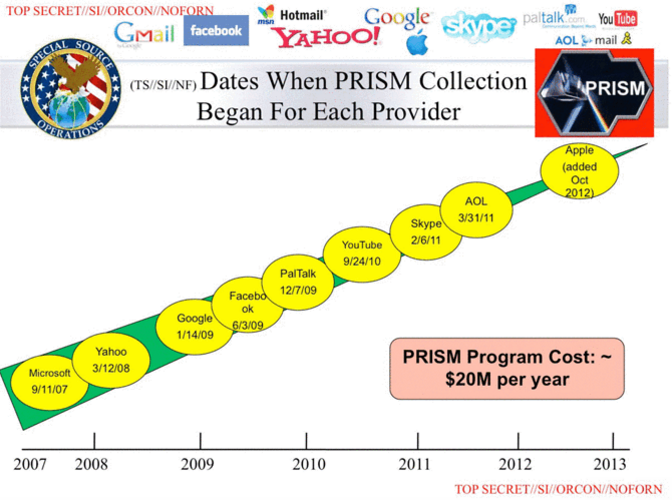

The debate has been ongoing since whistleblower Edward Snowden exposed the mass surveillance tactics of the National Security Agency and others in 2013, and it's in the forefront again following the Nov. 13 attacks that claimed the lives of 129 victims in the City of Light.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., criticized the tech industry Monday on MSNBC, claiming companies are not helping when it comes to the fight against the Islamic State. "I have actually gone to Silicon Valley, I have met with the chief counsels of most of the big companies, I have asked for help and I haven't gotten any help," Feinstein told MSNBC this week.

"I think Silicon Valley has to take a look at their products, because if you create a product that allows evil monsters to communicate in this way, to behead children, to strike innocents, whether it's at a game in a stadium, in a small restaurant in Paris, take down an airliner, that's a big problem," said Feinstein, who is vice chair of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

Some lawmakers may be mulling legislation that would require back doors. "At some point, this administration has to have a commitment to defeat terrorism, and it’s going to start with better intelligence, as we have seen from the Paris attacks," Richard Burr, a Republican senator from North Carolina and the chairman of Senate Intelligence Committee, told the Christian Science Monitor.

Another senator suggested to the Christian Science Monitor that an executive order from President Barack Obama should be forthcoming. "The president should come to us with what he needs to make sure we have the intelligence to protect our country," said Kelly Ayotte, a Republican senator of New Hampshire.

But the tech industry is resisting pressure from Washington and asking lawmakers not to present any bills that would require the creation of these back doors, a tool that the industry has long argued would make users and their data less secure.

"It's challenging to engage with public policy debates in the wake of such horrific attacks,” said Chris Riley, head of public policy for Mozilla, the maker of the Firefox browser, in a statement. “Yet, creating policy from a reactive posture is inherently problematic, even moreso when it would jeopardize critical components of the Internet and the economies we have built on it.”

In May, Mozilla along with a number of other tech industry leaders, including Apple, Google, Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo and Microsoft, signed a letter to Obama, urging him to reject any proposals that would require decryption keys or back doors. A few weeks later, a group of the world's top cybersecurity experts released a paper saying that the creation of back-door technologies would put sensitive data at risk of being compromised by hackers, terrorists or even just rogue federal agents or company employees.

"Good encryption protects people from hackers around the world, including the organizations responsible for the horrible attacks in Paris. Our priority is keeping our users safe, and back doors make them more vulnerable," said an employee of a public U.S. social networking company who was not authorized to speak on the record.

Cybersecurity experts also argue that creation of back doors for the U.S., France or other Western countries could set a precedent that would give governments of nations like China or Russia justification to ask for similar access. “How about the Germans, the Russians, the Chinese, the Syrians?” said Matthew Prince, CEO of CloudFlare, a cloud-computing and online cybersecurity. “I’m not sure how you draw the line between the U.S. government and a lot of the other governments where we have to do business as well.”

Police officials have used the Paris attacks as an example of why they want greater ability to peer inside devices and online services.

“We are very concerned in law enforcement that one of our most critical tools, the ability to gather intelligence through court orders as well as the laws we operate under, has been significantly impacted by this encryption technology that is growing rapidly,” said Bill Bratton, commissioner of the New York Police Department, on Tuesday at an event with officers. “It’s impeding our ability in terrorism; it’s impeding our ability in dealing with cybercrime.”

U.K. Reviewing Back Door

Though Feinstein has called on Silicon Valley to create back doors, no legislation has yet been introduced in the U.S. that would force the matter. The United Kingdom, however, is facing a different situation. There, Parliament must decide on the Investigatory Powers bill, or the so-called Snoopers’ Charter, which would expand the government’s ability to monitor users’ online activity. The proposed law has been criticized by the likes of Snowden and Apple CEO Tim Cook.

“Any back door is a back door for everyone,” Cook told The Telegraph, prior to the Paris attacks. “Everybody wants to crack down on terrorists. Everybody wants to be secure. The question is how. Opening a back door can have very dire consequences.”

The Paris attacks have lead some supporters of the Snoopers Charter to call on a fast-tracked adoption of the bill lest the U.K. fall victim to the next terrorist attack. Those in Silicon Valley argue the bill would lower users’ security online and lead startups to avoid operating in the country.

“Some startups are thinking about excluding the U.K. from the market, not for ideological reasons but because now another certification is needed prior to market that costs time and money and at the same time introduces a further security risk,” said Gerald Friedland, who works on technical privacy research at the International Computer Science Institute at Berkeley. “This security erosion would be a big win for the terrorists.”

Practically speaking, it would be difficult for U.S. tech companies to comply with foreign requirements for back doors without having to implement them universally. "If other countries set the bar lower in regards to devices there's going to be a weak point," said Peter Toren, partner at Weisbrod Matteis & Copley and a former prosecutor with the Justice Department's Computer Crime & Intellectual Property section.

Standing Together

It’s not just the tech industry that is against back doors. Bernard Kerik, the New York City Police Commissioner during the attacks on 9/11, has also opposed this type of government surveillance. Kerik, who was sentenced to four years in prison in 2010 for tax evasion and lying to government officials and now works as a consultant, told the International Business Times that back-door technology would simply give the government an open warrant to collect anything it wants.

“I do not believe that the Justice Department should be able to go to Twitter and ask for anything,” Kerik said. “If they have a warrant, if it's a justified investigation, that’s okay. My problem [with a back door] is what if it's not terrorists? What if you have a rogue investigator for their own purposes?”

But still, there are some companies that seem willing to comply. ASKfm, for example, which has been under scrutiny since it was revealed that the anonymous social network was used by the Islamic State to recruit three teenage girls from Denver, said in a statement that it is “committed to partnering with industry peers, government and law enforcement authorities to develop effective solutions."

ASKfm did not say whether it was specifically for or against the integration of back-door access. "Like any global social platform, ASKfm is committed to striking the right balance between safety and privacy. Though well intended, the industry needs to think carefully about the implications of backdoor access," the company said in another statement.

If the tech industry can weather the pressure it’s facing now for a few months, it could all blow over, said Kerik.

“In this first 90 days, you're going to have Congressmen call,” he said. “You have people who are going to say give Paris whatever they need. I'm all for that as long as it's in the guidelines of the Constitution.”

Salvador Rodriguez reported from San Francisco, and Kerry Flynn reported from New York.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.