Pianist Vs. Muezzin: Atheist On Trial For Insulting Islam In A Divided Turkey

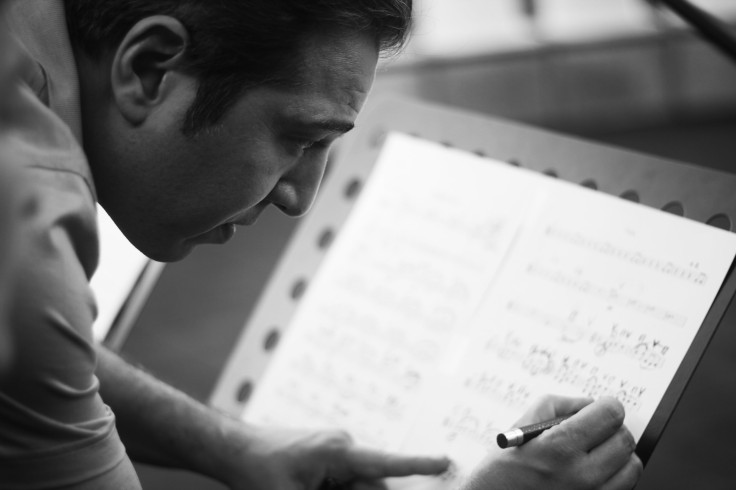

Composer and pianist Fazıl Say is known for building bridges between cultures -- but today, he seems about ready to burn them.

The eccentric musician was born in Turkey, where he wrote his first piano sonata at the age of 14. He spent much of his adult life in Europe and the United States, gaining recognition and a devoted following.

His piano performances are moody and organic, often drawing on historical themes. His orchestral compositions mix European rhythms with Turkish instruments, like the kudüm (a double-set of copper drums) and the ney (a traditional flute).

Say, 42, is also a colorful personality and an outspoken atheist -- and that’s what has lately landed him in hot water.

It was a series of Twitter posts that did him in. In one tweet, Say boasted about his atheism. In another, he poked fun at a local muezzin whose call to Muslim prayer lasted for less than half a minute. (They typically go on for about two minutes, and in some countries even longer than that.)

“The muezzin finished the call to prayer in 22 seconds. What’s the rush? A lover? A raki [alcoholic drink] on the table?” said the post. Say has since deleted his Twitter account.

In April of this year, Say was put under investigation for insulting religious values and inciting hatred. The courts accepted his indictment in June.

“I have to clear these charges against me,” he said at the time, according to Newsweek. “I did not insult Islam.”

On Thursday this week, Say appeared at his scheduled court date in Istanbul to defend himself. He denied the charges, and the case was adjourned until February.

Over the last decade, many other artists and intellectuals have also been charged with insulting either Islam or Turkey itself, including Nobel Literature Prize winner Orhan Pamuk, archaeologist Muazzez İlmiye Çığ, and novelists Elif Şafak and Nedim Gürsel. None was ultimately convicted of a crime, and it is likewise unlikely that Say will serve time behind bars.

But the case is still of monumental importance. That a world-renowned pianist could be indicted for joking about Islam is worrisome to the country’s many secularists, and this gets to the heart of Turkey’s central dichotomy.

Say is a vocal critic of the increasingly Islamist government in Turkey, and a great many Turks stand behind him. For this country of 74 million, which straddles East and West both culturally and geographically, a serious self-discovery is under way.

The country has had no official religion since 1923, when Mustafa Kemal (commonly referred to as Atatürk, or Father Turk) led a secularist revolution in the crumbling Ottoman Empire and founded the Turkish Republic.

But secularism has been on the decline since 2002, when the moderately Islamist Justice and Development Party, led by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, took control of the government. Since then, a domestic power struggle between secularists and religious conservatives has engendered societal schizophrenia.

Atatürk remains an object of reverence; his framed portrait is ubiquitous in cities like Ankara, the capital; and Istanbul, the cosmopolitan city where atheists, Muslims, Christians and Jews live side-by-side amid towering skyscrapers and beautiful ancient mosques. But strict religious conservatism is still common in rural areas, where many communities are governed according to Islamic codes.

Turkey has solid ties to the West; it is a member of NATO and has long been a candidate to join the European Union. Then again, it has been on the EU accession list for 25 years -- longer than any other country. Meanwhile, the Arab Spring has given Turkey a fresh opportunity to play a leading role in the Middle East, and a devastating debt crisis in Europe has lessened the Western appeal.

In recent years, foreign relations have become tricky business in Turkey. Having long espoused the “zero problems with neighbors” policy espoused by Atatürk, Turkey has enjoyed strong relationships with such divergent nations as Syria and Israel. Both of those relationships have become strained in recent years.

Now, as the Syrian crisis exacerbates Sunni-Shia tensions across the Middle East, historically secular Turkey is playing the role of accidental vanguard for emerging democracies on the Sunni side of the divide.

In all aspects of society, the ideological clashes are evident. Public schools began offering lessons on the Quran this year, but secularists fought back hard in defense of math and science. Headscarves are nominally banned for women in the public sector, but that law is hotly contested and rarely enforced. Abortion has been legal for decades, but Erdoğan wishes he could abolish it.

Secular-minded Turks chafe at any hint of theocracy, so these collective developments are taken very seriously. Incidents like the trial of Say only rub salt in the wound.

Say himself is certainly annoyed with the charges against him. As Turkey struggles to find itself between West and Middle East, the pianist told Newsweek that he might choose… neither.

“I’ve lived abroad for 17 years, and perhaps it’s time to move on,” he said. “Moving to Tokyo is a possibility. I think living in the Far East will be good for me.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.