Pirates In Global Waters: In Somalia, Has The Business Model Fallen Flat For Criminals On The Oceans? Is High Sea Piracy Unprofitable?

It’s a tight squeeze for commercial vessels trying to move their goods between Europe and Asian markets -- but not as tight as it used to be.

Beginning in the Mediterranean Sea, ships have to pass through the Suez Canal and into the Red Sea. Then they navigate the narrow Bab-el-Mandeb -- Arabic for the “Strait of Grief” -- between the sandy coastlines of Yemen and Djibouti. Next comes the Gulf of Aden, which borders northern Somalia and opens up to the Arabian Sea.

Tens of thousands of ships pass through the Gulf of Aden annually, as do tens of billions of dollars in cargo, and about 4 percent of the world’s oil supply.

This high-value traffic has proven too tempting for criminals to resist, and so in recent years piracy -- an old scourge -- has exploded onto the scene with new intensity.

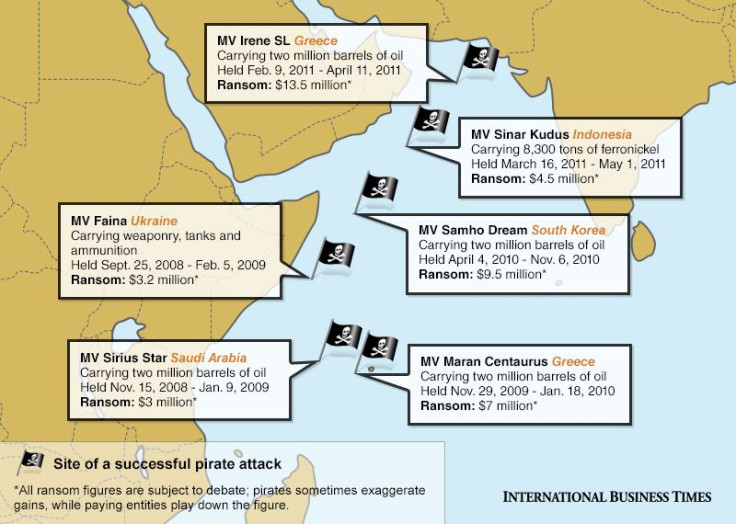

Since 2008, pirates based in the East African country of Somalia have launched hundreds of attacks against passing ships and held thousands of hostages. It’s ransom they’re after: On a good day, just one seizure can yield millions of dollars in profit.

But times aren’t what they used to be for these maritime criminals. The business of piracy has taken a nosedive in Somalia, and now lucrative old networks are falling apart at the seams.

Data compiled by the International Maritime Bureau, or IMB, show that piracy hit a five-year low in 2012. Only 28 ships were successfully hijacked. A total of 297 were attacked, down from 439 the year before and 445 the year before that. Those figures are global: In the areas surrounding Somalia, only 75 ships reported attacks last year, with 14 of them hijacked.

Tipping The Scales

As with all shady enterprises, the costs and revenue associated with piracy are difficult to pin down. One 2012 report by researchers at the London School of Economics and Political Science and the Institut d’Analisi Economica in Barcelona, Spain, estimated that during piracy’s golden years, its total gross revenue from ransom amounted to $200 million annually. Accounting for presumed operating costs leaves a net profit of around $120 million.

Even shared among thousands of pirates, criminal financiers, and go-betweens, that’s a big chunk of change for citizens of a country among the world's poorest, with no functioning government and nearly one-half the people living below the poverty line. Society is in such turmoil that even the World Bank has no current estimate for its gross domestic product per capita.

But the gains of Somali pirates are a pittance compared with the costs they force on the global economy. According to an Oceans Beyond Piracy report, the combined costs of increased security, insurance, rescue efforts, lost business, and ransoms amounted to between $6.6 billion and $6.9 billion in 2011. At least 80 percent of those costs are incurred by the shipping industry alone.

Human costs are also high. Another Oceans Beyond Piracy report tallied up the deaths and found that 35 hostages lost their lives as a result of pirate captivity in 2011. These tragedies result from attacks, malnutrition, or simply getting caught in the crossfire. In total, 1,206 people were held hostage by pirates that year, and 57 percent of them reported mistreatment, including abuse and employment as human shields. Also during that year, 111 Somali pirates died in clashes.

Despite all this, the hijackers don’t see themselves as bad guys -- or so they say. Many argue their original goal was to stop foreign vessels from invading their waters and fishing in their territories.

Illegal fishing is indeed a problem for many African countries. Foreign trawlers regularly invade the nautical territories of poverty-stricken nations that lack defense resources. The crews use irresponsible and wasteful fishing methods, harming marine life and ultimately depleting supplies for communities that rely on fish for sustenance and commerce.

The extent to which Somalia is affected by illegal fising is difficult to judge, in part becuase the country is one of the most obscure places on earth in terms of reliable data. But it is clear that although Somalia has the longest coastline in Africa, its main export is livestock, not fish. Furthermore, Somalia has never officially laid claim to its own Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ.

“Legally, every nation has jurisdiction up to 12 nautical miles from the coast,” explained Cyrus Mody, assistant director of the IMB. “Everything beyond that, up to 200 nautical miles from land, has to be declared. Somalia has not done that. If the country has not declared an EEZ, then, arguably, those waters are international.”

Mody added that, given the human-rights abuses committed by pirates, their claims of morality are hard to swallow. “You could say they’re trying to legitimize what they’re doing. But they are treating crews in captivity in an inhumane manner,” he said.

Keeping It Local

Most of Somalia’s piracy is based in the northern semiautonomous region of Puntland, with some spillover farther south into Galmadug and central Somalia.

The criminals had their heyday between 2008 and 2011. Kingpins enjoyed lavish lifestyles complete with fancy cars, showy villas and, most important, lots of khat -- a bitter leaf that, when chewed, acts as a stimulant and plays a role similar to that of espresso in Western countries. But even the high rollers have lately seen their incomes dwindle and their creditors come calling.

Canadian journalist Jay Bahadur, author of "The Pirates of Somalia: Inside Their Hidden World," spent a total of three months living among Somali pirates in 2009. A connection to the son of Abdirahman Farole -- who was elected Puntland’s president on Jan. 8 of that year -- helped him to stay out of danger, and Bahadur got a rare glimpse of the pirate lifestyle during its peak.

As it turned out, 2009 was the beginning of the end for pirates in Puntland. Farole put anti-piracy initiatives high on his political agenda, and his administration proved more successful than its predecessors.

“One of the things the new government was able to do was go into Eyl [a coastal town and piracy hub] and secure it, and this was in part because the president was from the same clan as many of the people there,” Bahadur said.

Although they were helped by international naval patrols at sea, these local efforts played a significant role in hampering pirates’ activities on land.

Puntland was able to pursue its anti-piracy campaign with a high degree of autonomy. It essentially functions as a nation-state, since a kaleidoscope of militant gangs farther south have made Somalia’s capital city of Mogadishu too weak to assert its power.

That may be precisely why piracy was able to thrive in Puntland.

“For pirates, Puntland had a perfect blend of security and insecurity,” Bahadur said. “There weren’t other armed gangs to interfere with pirates’ activities, but at the same time security was just lax enough for them to operate.”

The situation has grown more complicated over the past year, with Somalia taking baby steps to cobble together a functional government after two decades of failed statehood. A new administration was put in place in September. It was not popularly elected; that would be a logistical nightmare at this point.

The young government is plagued by corruption, but President Hassan Sheikh Mohamoud has been welcomed into the international community. Aid flows into the poverty-stricken country are increasing, and the United Nations Security Council voted this week to partially lift an arms embargo against Somalia for a trial period of one year. Restrictions on heavy weaponry are still in place.

Mogadishu’s law-enforcement capabilities -- especially on the high seas -- remain light, but Mohamoud has made some effort to combat the piracy problem. In late February, he released a statement suggesting amnesty for younger pirates, to draw new recruits away from a life of crime.

“It’s kind of symbolic,” Bahadur said. “But pirates are willing to do it because they have nothing else to gain. When you’re a pirate making calculations, the fact that piracy is less profitable has to factor in.”

Walking The Plank

Piracy was once an attractive option for young Somalis looking for a quick shilling, but it has increasingly lost its luster.

Commercial ships passing through the Bab-el-Mandeb and Gulf of Aden have responded to increased risks by beefing up their own security. It’s a simple solution, though not a cheap one. Armed guards have tended to be effective deterrents for Somali pirates, who could wait for more vulnerable prey given the high volume of ships passing through these waters.

But as more vessels began armoring up, the pickings grew slim.

“Because the commercial vessels started arming themselves so well, the types of vessels these pirates could get their hands on in late 2011 and 2012 did not belong to owners who were able to afford multimillion-dollar ransoms,” Mody said. “The catch was not as rewarding.”

To add insult to injury, commercial vessels are no longer going it alone. Keen to protect the valuable exports and imports passing around the Horn of Africa, various navies -- representing European Union nations, NATO countries and independent states -- have swooped in to offer another level of protection.

Personnel on these ships can be more proactive than crews on commercial vessels. In international waters, naval forces can pursue suspicious skiffs, arrest crew members and seize equipment.

Feeling more and more tightly squeezed, Somali pirates realized their market was shrinking and decided to raise their prices in compensation. Scoring millions of dollars, rather than hundreds of thousands, became the ideal. But that backfired, since demanding higher ransom only drags out the negotiation process. Pirates thereby incurred extra costs, since they had to keep seized vessels running and feed their hostages. Profit margins continued to shrink.

“It has become more difficult for pirates to successfully hijack ships, and the financiers who put money into these ventures are coming back with a loss,” Mody said. “That has contributed to a rethink on the part of the pirates as to whether this business model, which used to be extremely lucrative in the initial years, is not that lucrative anymore.”

Although Somali piracy is on the decline, it’s not over yet. Incidents are still occurring in the Horn of Africa and around the world. So far this year, 44 attacks are on record with the IMB. There are seven vessels and 113 hostages currently in captivity.

“We’re not there yet,” Mody said. “We are still advising extreme caution while going through these areas because there are still sporadic incidents occurring.”

Some areas within Somalia -- such as Puntland, where so much piracy is based -- offer signs of hope. Farole, whose familiarity with clan-based politicking has been a major boon to his political efficacy, is determined to tackle the piracy problem. Under his administration the Puntland Maritime Police Force, or PMPF, was deployed in early 2012. While international navies did their part at sea, PMPF dismantled piracy strongholds on land.

The PMPF, mainly funded by the United Arab Emirates, was frowned upon by the U.N. due to concerns about a lack of oversight, a risk of destabilization, and violations of Somalia’s arms embargo. Moving forward, it seems that a Mogadishu-based approach will do more to lend legitimacy to domestic anti-piracy efforts. Meanwhile, disillusionment may already be changing attitudes on the grassroots level.

“There have been independent efforts in communities along the Gulf of Aden,” Bahadur said. “The local people chased the pirates out. I think these communities got a bit irritated about pirates driving up prices and corrupting local economies, corrupting women and youth, and bringing in drugs and alcohol.”

The scourge won’t end soon, but it’s headed in the right direction for now.

These are times of great potential and enormous challenge for Somalia, which sits at the crossroads of commerce but comes from 20 years of chaos and failed statehood. Mogadishu is making its way, with help from the international community, toward a time when a long-divided country can come together and piracy can give way to economic networks that are sustainable, legal and inclusive -- the kind of buried treasure all Somalis can take part in.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.