Democrats Help Corporate Donors Block California Health Care Measure, And Progressives Lose Again

As Republican lawmakers grapple with their unpopular bill to repeal Obamacare, Democrats have tried to present a united front on health care. But for all their populist rhetoric against insurance and drug companies, Democratic powerbrokers and their allies remain deeply divided on the issue — to the point where a political civil war has spilled into the open in America’s largest state.

In California last week, Democratic state Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon helped his and his party’s corporate donors block a Democrat-sponsored bill to create a universal health care program in which the government would be the single payer.

Rendon’s decision shows how progressives’ ideal of universal health care remains elusive — even in a liberal state where government already foots 70 percent of the total health care bill.

Read: The Big Corporate Money That’s Fighting Single-Payer

Until Rendon’s move, things seemed to be looking up for Democratic single-payer proponents in deep blue California, which has been hammered by insurance premium increases. There, the Democratic Party — which originally created Medicare — just added a legislative supermajority to a Democratic-controlled state government that oversees the world’s sixth largest economy. That 2016 election victory came as a poll showed nearly two-thirds of Californians support the creation of a taxpayer-funded universal health care system in a state whose population is roughly the size of Canada — which already has such a system.

California’s highest-profile federal Democratic lawmaker recently endorsed state efforts to create single-payer systems, and 25 members of its congressional delegation had signed on to sponsor a federal single-payer bill.

Meanwhile, after Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger had twice vetoed state single-payer legislation, California in 2010 elected a governor who had previously campaigned for president on a pledge to support such a system. Other statewide elected officials had also declared their support for single-payer, including the current lieutenant governor, who promised to enact a universal health care program if he is wins the governorship in 2018.

None of that, though, made the difference: Late Friday, Rendon announced that even though a single-payer bill had passed the Democratic-controlled state senate, he would not permit the bill to be voted on by the Assembly this year.

“As someone who has long been a supporter of single payer, I am encouraged by the conversation begun by Senate Bill 562,” Rendon said. But “senators who voted for SB 562 noted there are potentially fatal flaws in the bill, including the fact it does not address many serious issues, such as financing, delivery of care, cost controls, or the realities of needed action by the Trump Administration and voters to make SB 562 a genuine piece of legislation.”

Since 2012, Rendon has taken in more than $82,000 from business groups and healthcare corporations that are listed in state documents opposed the measure, according to an International Business Times review of data amassed by the National Institute on Money In State Politics. In all, he has received more than $101,000 from pharmaceutical companies and another $50,000 from major health insurers.

In the same time, the California Democratic Party has received more than $1.2 million from the specific groups opposing the bill, and more than $2.2 million from pharmaceutical and health insurance industry donors. That includes a $100,000 infusion of cash from Blue Shield of California in the waning days of the 2016 election — just before state records show the insurer began lobbying against the single-payer bill.

While Rendon oversees a supermajority, it had never been clear that Assembly Democrats would muster the two-thirds vote needed under the state constitution to add the new taxes needed to fund the single-payer system proposed by the senate-passed bill. That’s because the Democratic Assembly caucus includes progressive legislators but also more conservative members who are closer to business interests.

In addition to the money given to Rendon, the groups opposing the single-payer measure have delivered more than $1.5 million to Democratic assembly members since the 2012 election cycle. In all, the 55 Democratic members of the 80-seat Assembly have received more than $2.7 million from donors in the pharmaceutical and health insurance industries in just the last three election cycles.

Complicating matters for this year’s single-payer bill was the fact that the pharmaceutical industry had just spent more than $100 million to defeat a 2016 ballot measure in California aimed at lowering drug prices. The wave of money was a powerful reminder that major industries opposed to single-payer have virtually unlimited resources to spend against California’s Democratic incumbents in the next election if those Democrats ultimately try to pass a bill.

“Subject To Enormous Uncertainty”

The episode in California was the latest defeat for single-payer health care advocates, who have faced a series of losses at the hands of Democrats whose party has continued to attract significant cash from the health care industries that benefit from the current system.

In the last decade, Barack Obama raised millions of dollars from health care industry donors and then backed off his previous support for single-payer. He and other administration officials explicitly declared that the Affordable Care Act would not become a Medicare-for-all system. The Democratic-controlled U.S. Senate then failed to pass a proposal to create a publicly run insurance option to compete with private insurers.

More recently, Vermont’s Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin abandoned his state’s high-profile push for single-payer in 2014 — just as he was serving as chairman of the Democratic Governors Association, a group whose top donors included UnitedHealthcare, Blue Cross, AstraZeneca and the pharmaceutical industry’s trade association.

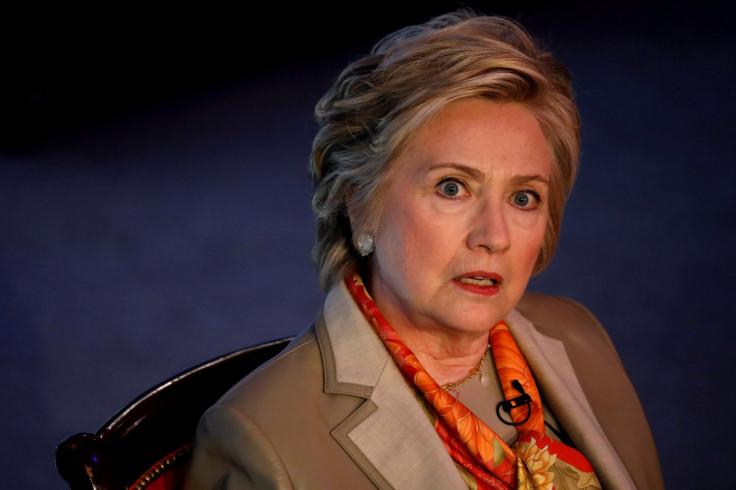

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s campaign was boosted by millions of dollars from health care industry donors, and she derided Bernie Sanders for pushing single payer, saying such an idea would “never, ever come to pass.” In the same 2016 election, prominent Democratic Party consultants helped lead an insurer-funded campaign — backed by prominent Democratic lawmakers — to kill a single-payer ballot measure in Colorado.

Despite those defeats, single-payer advocates were hopeful at the beginning of 2017. Heading into the new legislative sessions, Democrats controlled both governorships and legislatures in six states — and another Democratic-leaning state with a Democratic governor, New York, appeared to have legislative support for single-payer. With its Democratic supermajority, California was the biggest focus of attention among progressive health care advocates.

According to a June report by California senate analysts, the single-payer legislation that was introduced in Sacramento this year would have created a government agency called Healthy California that would be “required to provide comprehensive universal single-payer health care coverage system for all California residents.” The program would have been prohibited from charging participants premiums and co-pays and would have covered “all medical care determined to be medically appropriate by the members’ health care provider,” according to the Senate report.

While the report said fiscal estimates “are subject to enormous uncertainty,” it projected that $200 billion worth of existing federal, state and local health care spending would offset about half of the estimated $400 billion annual cost. Shifting that money, though, could require California to secure waivers from the federal government that would allow it to redirect the federal money into the new program.

The original bill did not include a specific tax proposal to raise the rest of the needed revenue. However, the report estimated that the other $200 billion could be funded by moving state payroll taxes up to 15 percent , a levy the report said “would be offset to a large degree by reduced spending on health care coverage by employers and employees.”

“The Only Health Care System That Makes Any Sense”

At the start of California’s legislative session, bill proponents pitched the sweeping measure as a way to protect the state from Trump administration health care policy. They may have been banking on support from California’s top Democrat, Gov. Jerry Brown, who endorsed single payer during his 1992 presidential campaign.

“I believe the only health care system that makes any sense is a single-payer system,” Brown said during a March 1992 Democratic presidential forum. “I don't see any way, after having worked on this problem in the largest state in the union, which, after all, has the highest medical costs, to really contain costs without establishing a single payer for all basic services.”

But as the the California legislation began moving forward, Brown cast doubts on it in comments to reporters in March.

“Where do you get the extra money?...This is the whole question. I don’t even get ... how do you do that?” said Brown, who has collected more than a quarter-million dollars of campaign contributions from groups opposing the bill.

Supporters of the legislation tried to answer the governor’s question with a detailed economic analysis asserting that the legislation could save the state money through lower administrative costs and drug prices.

“Providing full universal coverage would increase overall system costs by about 10 percent, but ... single payer system could produce savings of about 18 percent,” concluded a May 2017 study led by University of Massachusetts-Amherst economist Robert Pollin. “The proposed single-payer system could provide decent health care for all California residents while still reducing net overall costs by about 8 percent relative to the existing system.”

That same month, U.S. House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi — California’s highest-ranking federal official — seemed to give the idea a boost. At a Capitol Hill press conference, she said “the comfort level with a broader base of the American people is not there yet” for a federal Medicare-for-all bill, but she promoted state efforts.

“I say to people, if you want that, do it in your states. States are laboratories. It can work out. It is the least expensive, least administrative way to go about this,” she said. “States are a good place to start.”

Economist Pollin echoed that argument, telling IBT that the California situation is fundamentally different than Vermont, which in 2014 abandoned its high-profile effort to create the nation’s first state-based single-payer system. While single-payer could still be feasible in small states, he said, the concept was particularly well suited to a very large state like California.

“The issue of bargaining power is important relative to pharmaceutical companies, and that’s one big area of savings,” he told IBT. “If the pharmaceutical companies say we’re not interested in selling to Vermont, they can walk away from Vermont. But they can’t do the same thing with California because it’s too large a market. It’s the same thing with doctors — they are not going to run away from a market of 33 million people just because their reimbursement rates will be at Medicare levels. And the state of California is already used to running big operations, so it has the administrative power to do this kind of thing.”

“Woefully Incomplete”

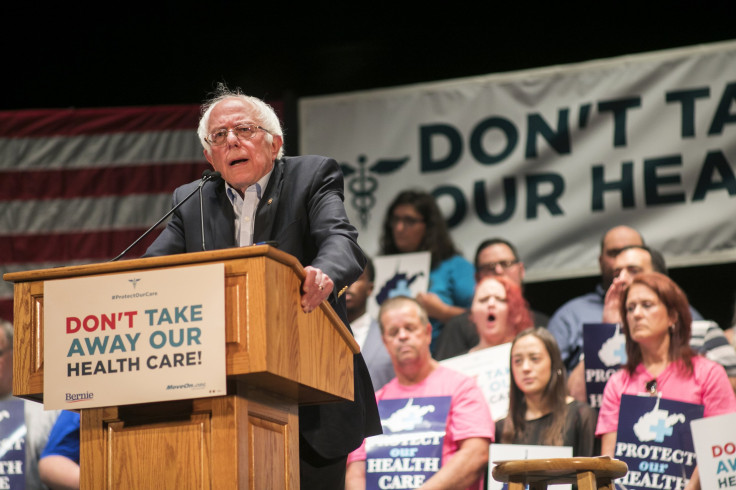

Despite Brown’s lack of support, and opposition from Republican lawmakers and health insurers, the California senate passed the single-payer bill in June. Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders pressed the Democratic governor and California lawmakers to enact the bill.

“As we sit here tonight, the California state senate has passed single-payer,” Sanders told a gathering of thousands of activists in Chicago. “Now it’s up to the California House and the governor to do the right thing and help us transform health care in this country by leading the way.”

All of the pressure was not enough to persuade Rendon. Calling the legislation “woefully incomplete,” he announced that “SB 562 will remain in the Assembly Rules Committee until further notice.”

The move was instantly polarizing. Inside the labor movement, the California branch of the Service Employees International Union — which has long supported single-payer health care — issued a statement supporting Rendon’s decision, saying the organization wants changes to the legislation. SEIU’s affiliates have previously negotiated a collective bargaining agreement with insurer Kaiser Permanente, which would be “dismantled” under the single-payer bill, according to Kaiser’s lobbyist.

By contrast, the California Nurses Association, which represents 100,000 unionized nurses in the state, slammed Rendon, asserting that he had acted “in secret in the interests of the profiteering insurance companies” and that he had “destroy[ed] the aspirations of millions of Californians for guaranteed health care.”

The internecine attacks were equally fierce within the Democratic Party.

“Today’s announcement that the Assembly will not be moving forward on single-payer, Medicare-for-All healthcare for California at this time is an unambiguous disappointment for all of us who believe that healthcare is a right for every Californian,” said newly elected California Democratic Party chairman Eric Bauman, who until the middle of June had worked in the Assembly speaker’s office under Rendon, and ran his Southern California office. “We understand that SB 562 is a work in progress, but we believe it should keep moving forward, especially in light of the widespread suffering that will occur if Trump and Congressional Republicans succeed in passing their cold-blooded, morally bankrupt so-called healthcare legislation.”

Perhaps seeking to bridge the divide, Rendon left open the possibility that the bill will come up next year.

“Because this is the first year of a two-year session, this action does not mean SB 562 is dead,” he said. “In fact, it leaves open the exact deep discussion and debate the senators who voted for SB 562 repeatedly said is needed. The Senate can use that time to fill the holes in SB 562 and pass and send to the Assembly workable legislation that addresses financing, delivery of care, and cost control.”

Rendon’s focus on financing underscored the fact that passing tax increases to generate hundreds of billions of dollars of new revenue is generally no easy political task — and such initiatives can be particularly tricky in California. There, a 1988-passed measure called Proposition 98 typically requires that a significant amount of any new tax revenue must go to education. Another 1979 measure known as the Gann limit also aims to restrict spending increases. Funding a single-payer system could require complex legislation or even a separate ballot measure.

Bill proponents, though, say those potential roadblocks are navigable within the scope of the bill they are pushing. In an interview with IBT, Michael Lighty of the California Nurses Association noted that the Senate version of the legislation included language to make sure that the new health care system would not launch unless state officials certified that adequate funding was available.

“The speaker says the bill is ‘woefully incomplete’ but he stopped the process that would have completed it,” Lighty said. “We have a failsafe mechanism in the legislation. In the event anticipated monies are not available from whatever source for whatever reason, we can address it before full program operation. There are all sorts of options, but you can’t do any of it if the bill doesn’t move forward.”

Bauman told IBT that despite the opposition within his own party, he expects progressive Democrats to continue pushing for single payer.

“What Democratic activists need to be doing every day is educating our elected officials and the public on just how important the fight for health care is, and on why this is the moral and ethical fight of the day,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.