Why Do Ivy League Schools Get Tax Breaks? How The Richest US Colleges Get Richer

During his successful quest to win Pennsylvania’s 20 electoral votes, Donald Trump told the state’s voters that colleges are fleecing taxpayers and enriching Wall Street.

“What a lot of people don't know is that universities get massive tax breaks for their massive endowments,” he told a crowd in suburban Philadelphia. “These huge multi-billion dollar endowments are tax-free, but too many of these universities don't use the money to help with tuition and student debt. Instead, these universities use the money to pay their administrators, or put donors' names on buildings, or just store the money away. In fact, many universities spend more on private equity fund managers than tuition programs.”

Trump promised to make universities’ tax breaks contingent on schools’ willingness to reduce tuition prices — and lawmakers are now considering bills to do just that. New data released this week could fuel those legislative initiatives.

According to a study by Stanford University scholar Charlie Eaton, universities are using their endowments to haul in more than $19 billion in tax subsidies every year. The analysis, which compiled data from 1976 to 2012, found that as the tax expenditures have flowed to college endowments, those endowments have exponentially grown — and have funneled billions to Wall Street money managers who make big fees off the pools of cash.

Despite the tax breaks and the flood of cash to Wall Street, many of the universities that benefit from the subsidies have refused to use their additional endowment resources to expand enrollment, admit more low-income students or lower their tuition rates.

“Private colleges with substantial endowment wealth have increasingly become ivory tower tax havens,” wrote Eaton, whose study was published by the University of California-Berkeley's Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society. “The metaphor encapsulates how exponential endowment growth at these colleges has been supported by large tax expenditures that disproportionately benefit a small elite.”

In the face of legislative initiatives to reduce their tax breaks, public and private universities have in recent years lobbied to influence the congressional debate about the policies governing endowments. Donors from the higher education sector have also made campaign contributions of millions of dollars to federal lawmakers. University officials and their trade associations have argued that critics of endowments and endowment-related tax preferences are undermining the key financial pillar of higher education.

“There is renewed pressure to force colleges with sizable endowments to spend more, and increased talk about revoking their tax-exempt status,” wrote Pomona College president David Oxtoby in a 2015 editorial for the Chronicle of Higher Education. “These attacks on endowments reveal both an extremely short-term outlook, and a fundamental misunderstanding of what they do and how they work. Endowment funds provide scholarship dollars for students and allow colleges to expand student access and diversity. They help ensure that support for faculty teaching and research remains a long-term institutional priority. They support libraries and other facilities, public service, and student success and retention programs.”

“Wealth And Extravagance At Very Wealthy Universities”

In the last three decades, college endowments have grown to more than half a trillion dollars — and they reflect the economic inequality that defines America’s larger society. According to a 2015 Congressional Research Service report, roughly three quarters of endowment wealth is now held by just 11 percent of universities.

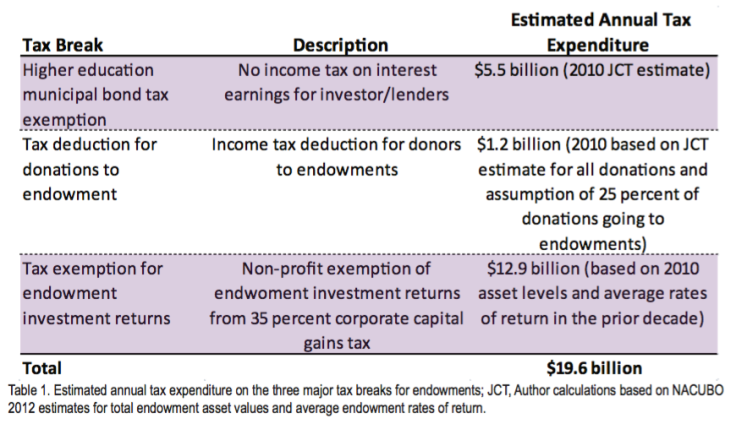

Eaton’s data shows that the growth in endowments — and the concentration of wealth at a handful of expensive elite schools with relatively small enrollments — coincided with the expanded use of three federal tax breaks formulated in an era before higher education became a major industry.

One tax break that costs $1.2 billion a year exempts donations to college endowments, meaning that wealthy benefactors of these schools can donate large sums and enjoy big write-offs.

Another annual break that costs $12.9 billion exempts universities’ investment earnings from capital gains taxes.

And a $5.5 billion break is the one that lets universities finance projects through tax-free municipal bonds rather than through their endowments. The latter essentially lets universities borrow money at tax-preferred rates and pay back a lower rate of interest than their endowments make through investments — a system Eaton calls indirect tax arbitrage.

Had endowments been used to dramatically reduce tuition or increase enrollment to make higher education accessible to more students, colleges would have little trouble arguing that the tax benefits serve an obvious public good. But Eaton’s report notes that enrollment at the wealthiest private undergraduate schools has remained flat since the mid-1970s, when endowments were a fraction of what they are now.

Rather than using rapidly growing endowments to increase enrollment and provide more educational opportunities, the wealthiest universities doubled their spending on individual student instruction, which Eaton says has a disproportionate impact on schools’ all-important college rankings — but hasn’t helped open their doors to more low-income students. Indeed, while elite public universities increased their percentages of low-income students, wealthy private liberal arts colleges and research universities saw barely any growth in those admissions.

Instead, a study led by Stanford’s Raj Chetty published in January found that the top universities admitted more students from families in the top 1 percent of earners than the entire bottom 50 percent. And while the universities with the largest endowments are often the most generous with financial aid, a 2015 ProPublica analysis found private universities with billion dollar endowments, such as New York University ($3.5 billion) and the University of Southern California ($4.6 billion), saddle low-income graduates with average debt burdens in excess of $20,000.

While admissions of low-income students has remained flat, what has increased is Wall Street largesse. According to recent data compiled by Preqin, hedge funds and private equity firms now together manage roughly $200 billion worth of endowments. At the standard 2 percent management fee rate, that means American college and universities are handing over roughly $4 billion per year to the finance industry at the same time schools are enjoying what Eaton says is nearly $20 billion in tax breaks.

Taken together, Eaton argues that the higher education system — which has been depicted as a force for social equality — has instead become an instrument of economic stratification.

“I looked at this because you could see mounting public outrage about lifestyles of wealthy people in the U.S. and I saw parallels in that about the amount of wealth and extravagance at very wealthy universities and private colleges,” Eaton told the International Business Times. “If very wealthy schools don’t do more to increase the social and educational benefit that they provide to citizens more broadly, than proposals for taxing endowments are likely to continue to gain steam.”

“Get Universities To Use The Money”

Legislative measures to tax endowments had been considered by Congress before the financial crisis of 2008 and the issue received renewed interest on the campaign trail last year. Trump, a graduate of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania (endowment: $10.7 billion ), openly slammed universities with “multibillion dollar endowments.” Meanwhile, the House Ways and Means Committee held a hearing to examine the relationship between endowments and tuition costs in September.

One of the members of that committee, Republican Rep. Tom Reed, an early Trump backer representing a rural New York district that is also home to Cornell University (endowment: $6 billion), is now preparing a bill that would implement new rules for wealthy endowments.

Reed’s legislation, called the Reducing Excessive Debt and Unfair Costs of Education (REDUCE) Act, would require any college or university with an endowment worth over $1 billion (or worth more than $500,000 per student) to invest 25 percent of yearly endowment gains to fund tuition for students from working class families.

The REDUCE Act would also tax large restricted donations. Those donations, which donors say can only be spent on certain departments or causes, make it difficult for schools to direct endowment funds to different areas of need, like financial aid, say endowment defenders. According to the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), more than 90 percent of donations to universities are restricted. Wealthy donors want to choose how their money is spent. If they can’t do that, they might not give at all, the schools argue.

“The goal in taxing endowments would be to get universities to use the money,” Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall who helps compile Washington Monthly’s annual college rankings, told IBT. “The drawback is that donors might not want to give.”

In Connecticut last year, some lawmakers sought to impose restrictions on Yale’s endowment, requiring the university to spend more of its earnings, or have them taxed. Their bill ultimately died in committee.

Yale spent more than $41,000 lobbying the Connecticut legislature in 2016, according to state records reviewed by IBT. That same year, Yale had more than half of its $25 billion endowment in private equity and hedge funds. In 2014, Yale paid $480 million to Wall Street money managers— far more than the $170 million it spent on tuition assistance, fellowships and prizes , according to University of San Diego law professor Victor Fleischer. The university has argued that the investments’ returns for the endowment justify the fees.

The legislative barrage is fueled, in part, by a growing sense that the largest endowments are swelling because schools are hoarding wealth for no other purpose than to battle for prestige. How much money does Yale need, for example, to make sure it never goes broke? In fiscal year 2016, universities participating in a survey conducted by the NACUBO spent just 4.3 percent of their endowments. In comparison, non-profit foundations are required to spend 5 percent of their wealth every year. University endowments are not subject to similar requirements.

“Most of these very wealthy institutions receive billions of dollars a year in federal tax money. We are talking about a lot of money,” said Shamus Khan, an associate professor of sociology at Columbia University and author of “Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul’s School.”

Ivy League schools, for example, received $25.73 billion worth of federal payments in contracts, grants and direct payments for student assistance between fiscal years 2010 and 2015, according to a report from Open The Books.

“What is the public accountability of these institutions given the public investment in them?” Khan asked in an interview with IBT.

“Encourage The States To Provide More Support”

Over the last year, the higher education industry has made big expenditures on lobbying to shape the congressional debate over the intensifying questions about endowments.

An International Business Times review of federal records found that in 2016, 22 schools and three higher education groups disclosed $4.9 million worth of spending on lobbying forms that listed endowment-related issues as one of the policy areas being worked on. Among those lobbying Congress on those issues were Harvard University (endowment: $35.7 billion), Princeton University (endowment: $22.2 billion), Cornell University (endowment: $6 billion) as well as public schools such as Indiana University (endowment: $1.9 billion), the University of Oregon (endowment: $753 million) and the University of Virginia (endowment: $4 billion).

The lobbying blitz was buttressed by campaign cash: in 2016, donors from 20 major universities collectively gave more than $21 million to candidates for federal office, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics. That sum does not include millions more from the private equity and hedge fund industries that have received ever-larger investments and fees from the tax-break-fueled growth of university endowments.

The well-financed political efforts to shape college tax preferences are backed up by some experts who argue that while huge endowments at elite private universities make easy targets for populist politicians, they have little to do with rising tuition costs. Approximately three-quarters of U.S. college students attend public universities, which have made do with smaller and smaller budgets as states continue to slash education expenditures. State spending per university student fell about 38 percent between 2001 and 2012, according to the group State Higher Education Executive Officers.

As a result, schools have been forced to hike tuition to fill budget gaps.

“To a large extent, what goes on at the rich private universities is irrelevant to the question of student debt,” Ronald Ehrenberg, director of the Cornell Higher Education Research, told IBT. “If we want to hold down tuition increases, we should look at the public sector.”

Ehrenberg said that while taxing endowments and denying tax benefits to donors are ways to redistribute income, those measures ultimately won’t help battle the growing student debt problem.

“I would rather prefer to think of ways to encourage the states to provide more support,” Ehrenberg said.

Whether or not federal tax and state funding policies are reformed, Eaton says some universities are already responding to the mounting criticism of endowments.

“Harvard, MIT, and Stanford have begun to experiment with mass online programs at low or no cost for those outside of their exclusive undergraduate cohorts (and) some liberal arts colleges have begun to increase enrollments of lower-income students,” he wrote. “It remains to be seen if other wealthy schools will follow suit and to what extent they will dip into their endowments to do so. And it is unclear if these initiatives can actually narrow the gap between an elite schools’ undergraduates and America at large. But the initiatives signal a recognition of the problem.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.