Ransomware Hackers A Bigger Threat Than Ever, Forcing Hospitals And Police To Pay Hostage Fees

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise. The cyberattack that left a California hospital paralyzed until administrators agreed to pay a $17,000 ransom is only the latest digital assault to hit a cash-strapped emergency-service provider in the U.S. But it’s the biggest evidence yet that ransomware should be a permanent concern for anyone or any business using the internet, and it’s going to get worse before it gets better.

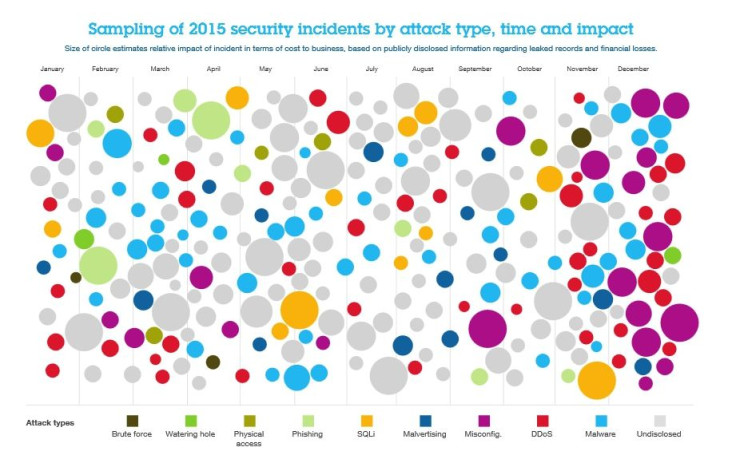

“Ransomware” is defined as any kind of malicious software that encrypts a computer’s sensitive data after infecting the machine or network. Victims hoping to regain access often have a limited time to pay a hostage fee (usually in bitcoin, because it’s hard to track) before permanently losing access to their data, or risk having their secrets published online. Ransomware typically accesses a user’s computer through a malicious email attachment disguised as a legitimate file, though there’s also been a spike in "distributed denial-of-service" attacks (known as DDos, which knock websites offline by overwhelming them with traffic), which abate only when demands are met.

Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center, a 420-bed Los Angeles hospital, is the most recent high-profile victim, with its executives announcing last week that they paid 40 bitcoins (worth roughly $17,000) to get free of an attack that locked staff out of patient medical records and other essential computer systems. A number of police departments in Massachusetts, Maine, Illinois and elsewhere throughout the U.S. have paid hostage fees to unlock their computers, as well.

“I’ve seen it as high as 100,000 new computers impacted per day,” said Chris Doggett, senior vice president at the cloud security company Carbonite and a former executive at Kaspersky Labs, adding that many targets never report being victimized. “When you look at various research sources, there are estimates of 3 to 5 million pieces of ransomware out there within any given time period. With ransomware they’re not taking information, so it doesn’t fit the need to report under traditional data-breach notification rules. The data is encrypted, not stolen, and there’s very little financial incentive to report it.”

The percent of ransomware attacks that specifically target hospitals or police stations is in the “single digits,” multiple experts say. Mostly, hacks start with mass email campaigns aiming to snare unwitting recipients. Hospitals, police agencies and other essential services fall victim because employees who have access to those networks are often busy, IT staffs are underfunded, and cybersecurity training is rare.

“They [hackers] throw out a wide chum net, and whoever bites, bites,” said Dodi Glenn, vice president of cybersecurity at PC Pitstop. “It’s a highly transactional business.”

Other victims are infected when they stumble upon a website hosting an advertisement that’s quietly infiltrating a computer’s firewall. In fact, it’s become so easy for hackers that ransomware attacks have increased by at least 160 percent every year since 2013, according to Roy Katmor, CEO of the data theft prevention company enSilo.

“Our numbers show that 44 percent of victims pay,” Katmor said. “A hospital will pay thousands, and someone at home will pay closer to $500. It’s a cost-benefits decision, and the cost of having someone from the cybersecurity industry try to solve this with forensic analysis costs at least $1,000 an hour.”

A report released by the Cyber Threat Alliance last year [PDF] determined that the team behind Cryptowall 3, one of the most notorious strains of ransomware, reaped $325 million for its developers. Cryptowall 3 was just one of the ransomware attacks an FBI special agent was referencing when he admitted last year that bureau cybercrime investigators “often advise people to just pay the ransom.”

It's impossible to know how many victims have been infected with ransomware, or how drastically ransom demands vary. But experts say there’s a lingering stigma among security researchers who say paying hostage fees helps attackers fund new strains of ransomware, and encourages them to continue their crime spree.

“I think some folks in the cybersecurity community who have spent all their time fighting cybercriminals are more hardened in resolve than ever,” said Doggett, who has repeatedly met with members of Congress to discuss cybersecurity issues. “The FBI is so inundated with cases that they’re often forced to work on cases that are much larger than $17,000. These [attackers] know that, and they make it super easy to unlock files really quickly.”

Ransomware strains are becoming increasingly complex and impossible to contain. The best way to avoid an infection is to plan on being infected anyway. The only catch-all way to mitigate the damage is regular data backups, in the form of either cloud storage or a physical hard drive.

“If I’m a business and these are documents that I don’t have them backed up anywhere else and the only option is to pay the ransom, then that’s what I’m going to do,” said Glenn. “Given the way backup programs have evolved and been improved, where you don’t need to back up everything or even take everything offline, there’s no reason for a company to have a backup once an hour. There really are no alternatives.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.