A Seismic Shift For Retirement Savers — And Their Advisers — Rumbles Through Washington

When Jim Hebenstreit left the television business in the early 2000s to become a financial adviser, his intentions were noble: He wanted to help ordinary people save for retirement. But pressure from management to meet quotas forced him to prioritize sales over measured advice. “I was kind of shocked,” Hebenstreit said, comparing his job to used-car sales. ‘“I thought I could be an investment adviser, and I found out I was really a salesperson.”

But the Labor Department wants to change that, upending industry norms by reducing conflicts and requiring heftier disclosures of commission-based sales. A proposed rule would require advisers of individual retirement accounts, or IRAs, to become so-called fiduciaries, mandating that clients’ best interests come first.

Working at a string of investment firms, including Fidelity and Wells Fargo, Hebenstreit felt deep conflicts between working in the client’s best interests and keeping his own job. “You’re constantly burying your feelings about being conflicted,” Hebenstreit said. “You have to make a living — and it’s not technically illegal.”

Though it comes as a surprise to many savers, many retirement advisers have no obligation to serve their clients’ best interests. Advisers are free under current law to recommend products that, unbeknownst to savers, generate higher commissions for the seller — and higher fees for the client.

The proposed rule change, which advanced a step Friday, has faced substantial resistance. Groups representing financial advisers warn that the rule is overly complex and could harm access to financial advice, especially for savers of modest means.

“We’re not debating should there be a requirement that retirement advisers should act in the best interests of their clients,” Dale Brown, CEO of the Financial Services Institute (FSI), said. “It doesn’t need to be so costly and complex that it pushes affordable retirement advice out of the reach of small investors.”

What will happen when the most consequential regulatory change to hit the industry in decades moves out of Washington and into the offices of financial advisers nationwide? Here’s what to expect, for savers and advisers alike.

What Does the Rule Do?

As the law currently stands, financial advisers who help individuals and families save for retirement do not have to work in their clients’ best interests, as so-called fiduciaries do. Instead, they must meet the “suitability” standard, a looser set of rules that ensure advice is appropriate for savers’ needs and risk appetites.

“They’re called advisers, but they’re regulated as salespeople, meaning they can put their own interests ahead of clients',” said Barbara Roper, director of investor protections for the Consumer Federation of America, which lobbied for the rule’s passage.

The Labor Department rule would change that, requiring advisers to become fiduciaries. The shift would essentially prohibit advice that is considered conflicted — that is, advice for products that pay advisers commissions. Some commission sales would still be allowed, but they would require pages of detailed disclosures.

In addition, limits would be placed on the sales of certain insurance products, like variable annuities, and other bespoke offerings.

What Does It Mean for Savers?

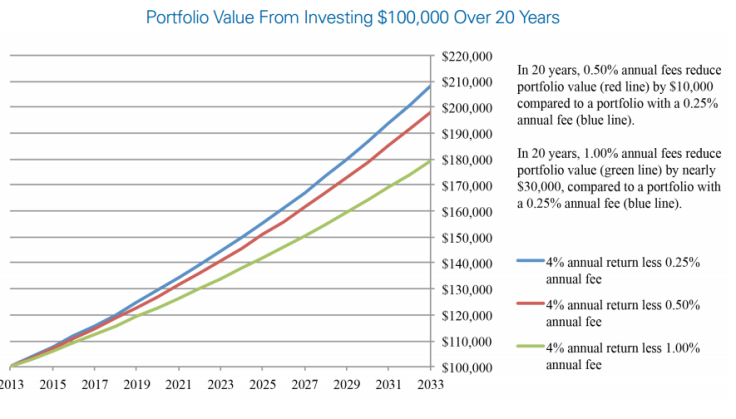

The fiduciary rule has the potential of keeping billions of dollars in the accounts of retirement savers that otherwise would be paid out in fees. The White House’s Council of Economic Advisers cited peer-reviewed studies that found conflicted advice leads to fees 1 percent higher than conflict-free advice. Over 20 years, a 1 percent drag on investments can erode returns by nearly 30 percent.

Overall, the council estimated savers lose roughly $17 billion a year in potential returns in fees on conflicted advice.

The FSI and other groups have disputed those numbers. But similar estimates have emerged from independent studies. Morningstar analyst Michael Wong calculated in 2015 a fiduciary rule would cost the industry $19 billion in revenue.

Clients would also see significantly enhanced disclosures before they signed off on financial advice, including a full rundown of how advisers were compensated. According to the Securities and Exchange Commission, savers “generally are not aware” of the compensation structures their advisers use.

More expensive structures would be “likely to come under significant scrutiny as a result” of the fiduciary rule, analysts with the consulting firm Oliver Wyman wrote in a report for the industry.

What Does It Mean for Advisers?

Consumer advocates and industry insiders agree, for the most part, the new rules won’t kill off the industry. “One of the core strengths of the independent-broker-dealer model is adaptability and flexibility,” Brown said. “These are entrepreneurs, they have a long history of adapting to changes in the marketplace.”

But neither will it leave advisers to go about their business as usual. ‘“It will completely change the way services are delivered,” Roper said. “That’s kind of the point.”

If the finalized rules look like previous versions, advisers have several options. They can apply for an exemption that significantly increases the disclosures advisers have to make before advising clients. Following that process, advisers could still earn commissions — provided clients sign off on the increased disclosures over compensation structures.

Otherwise, advisers will have to move toward a fiduciary model where they earn fees for advice, not sales. Major firms like LPL Financial have already begun shifting their models to align with this structure.

But industry leaders worry the rules could make financial advice less accessible to lower-income savers. Higher upfront commissions help subsidize the provision of financial advice to less affluent clients. With stricter rules around compensation, industry spokespeople say, these savers could lose out.

“Most small investors are overwhelmed by the variety of financial products available. They need access to a professional adviser,” said Brown, noting studies that have found advisers can play a role in instilling prudent investing behavior. “For most Main Street advisers, the most affordable way is through a commission-based arrangement.”

To Roper, this is part of the problem. “It’s not about limiting their access to advice, it’s about limiting access to sales pitches dressed up as advice.”

Both sides of the debate point to the experience of the U.K., which prohibited commission-based sales in 2012 under a much stricter regulatory regime than the Labor Department has proposed. In 2014 the British Financial Conduct Authority examined whether the new rules had the effect of cutting off access to less affluent savers.

The FCA found that the number of financial advisers fell in the years after the rules passed, and savers with less than $140,000 in savings opened fewer new accounts with advisers. But there was “little evidence that the availability of advice has reduced significantly,” the regulator wrote.

Where Does It Go From Here?

Last week the rule moved into the Office of Management and Budget where rules generally sit for 50-90 days before moving on. After that comes Congress, which has a 60-day opportunity to bar the rule, subject to a presidential veto.

The Obama administration, with help from progressive Democrats like Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., has pushed hard to move the rule along. Obama hopes to see it cemented before he leaves office, opening up the possibility an unfriendly administration could quash the effort. Since the finalized rules haven’t been made public, it is possible a yearslong delay was built into the policy as industry groups sought.

“Time is of the essence,” Roper said.

The rule continues to face resistance in Congress. Ann Wagner, a top opponent of the rule, has pushed legislation that would prevent the Labor Department from issuing the rules until the SEC does so, a process that could drag on several more years. “This fight is far from over,” Wagner said Friday.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.