SpaceX Rocket Explosion: Can The Commercial Space Industry Recover From The Falcon 9 Rocket Failure?

A spacesuit, a flexible exercise band, toilet paper, a projector screen, two Microsoft HoloLens headsets and a water filtration system – these are just a few of the supplies that were packed inside the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket that exploded just moments after liftoff on Sunday. The astronauts that were patiently awaiting the delivery at the International Space Station will have to do without for a while longer.

Meanwhile, industry leaders are dealing with a different kind of post-explosion reality as it tries to temper public skepticism and spread the message that the commercial space sector is wholly prepared to withstand and overcome such failures.

The SpaceX rocket failure isn’t the only catastrophe to befall the industry in recent months. Last October, an Antares rocket operated by Orbital Sciences Corp. carrying 5,000 pounds of supplies bound for the space station perished shortly after launch. In April, a Russian spacecraft named Progress that was packed with 6,000 pounds of supplies breached low orbit, but whirled out of control before plunging back to Earth.

The explosions underscore the risks inherent in space innovation and repeated failures could have spillover effects for the rapidly-growing commercial space industry. Overall, the estimated 800 companies in the commercial space sector are predicted to rake in $10 billion in private investment in 2015 alone. That's roughly the amount that has been poured into the top 100 private space companies over the past decade. In 2010, SpaceX was valued at $250 million but the company raised money at a valuation of $12 billion this year after Google announced a $900 million commitment.

Jeffrey Manber, managing director of NanoRacks, sounded dejected in a phone interview Monday. His company handles the logistics of space flight and had booked cargo on both the SpaceX and Antares rockets for clients eager to send experiments and equipment skyward. The company has successfully launched more than 200 payloads, but the double-whammy of two failed space flights in a year is taking a toll.

“Clearly, we don't have down what it takes to send something to and from space,” he says. “It's still clearly a frontier. We'd like to think that it’s not but it's clearly still a frontier.”

Manber suspects the explosion will cool investor expectations and says a slight downward adjustment might actually bring the industry's hype back in touch with reality.

“This may put a little realism in the extraordinary excitement surrounding commercial space and I have no problems with that realism coming in,” he says. “Just like in software when you have product coming out with bugs, this is just a sobering reminder that you're going to lose vehicles and there are going to be setbacks.”

Representatives of the commercial space industry say failures come with the terrain. Amir Blachman, managing director of a fundraising group called Space Angels, says investors expect progress to come in fits and spurts. He is confident that space companies and their backers will take the rocket’s loss in stride.

“While this is a setback, I think investors see this as a hiccup along the way,” he says.

Jeff Feige, chairman of the Space Frontier Foundation, echoes that sentiment and points out that SpaceX successfully launched 18 Falcon 9 rockets before logging its first failure. “For the moment, this is kind of a shrug,” he says. “If we have a few more, then it's something to talk about.”

Manber says that his company can sustain these losses, up to a point – but the quick succession has dealt a particularly hard blow. “This really hits us hard,” he says. “We've taken a hit in revenue. It’s something that we plan for but it's still not easy when it happens.”

In a press conference on Sunday, Bill Gerstenmaier, associate administrator of NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, acknowledged that the SpaceX rocket failure was a tough loss, but expressed optimism about the company’s ability to troubleshoot the malfunction, which Elon Musk tweeted may be related to an “overpressure event” in a tank of liquid oxygen.

"The teams will work through this,” Gerstenmaier said. “We'll learn from these events and I think we'll get stronger from these events."

Gwynne Shotwell, president and chief operating officer of SpaceX, expressed confidence in Sunday’s press conference that the company would fix the malfunction and said she expects to still launch the first crewed SpaceX mission in 2017.

Both Manber and Feige agree that such failures underscore the value of having multiple commercial providers to run space flights, so that lost cargo can quickly be re-booked in the event of a catastrophe.

This week, SpaceX and NanoRacks aren’t the only ones feeling the impact of the failed mission. The rocket was carrying just over 4,000 pounds of cargo and much of the load was supplies for the space station, including a special docking adapter that would have enabled future spaceships to latch onto the space station with ease built as part of a $100 million program (fortunately, NASA has a spare).

Mike Suffredini, manager of the International Space Station Program for NASA, said in the press conference that astronauts on board the space station have enough supplies to last until the next resupply mission. Astronaut Scott Kelly said he was particularly excited to test the virtual reality capabilities of the Microsoft HoloLens a few days before the launch.

I'm looking forward to testing the #microsoft #HoloLens when it arrives on @Space_Station next week. #YearInSpace pic.twitter.com/8TDusXR7MJ

— Scott Kelly (@StationCDRKelly) June 27, 2015"This is a blow to us,” he said. “We lost a lot of important research equipment on this flight."

Michael Fortenbary, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas lost an experiment for the second time in Sunday’s failure after his first test expired in the Antares explosion. He is trying to send up a visible spectroscopy instrument to monitor meteors from space. This instrument will capture the first space-based image of a meteor entering the Earth’s atmosphere and may lead to clues about how the planets were formed. When reached for comment on Monday, Fortenbary was heading into a meeting to determine what path to pursue after two failed launches.

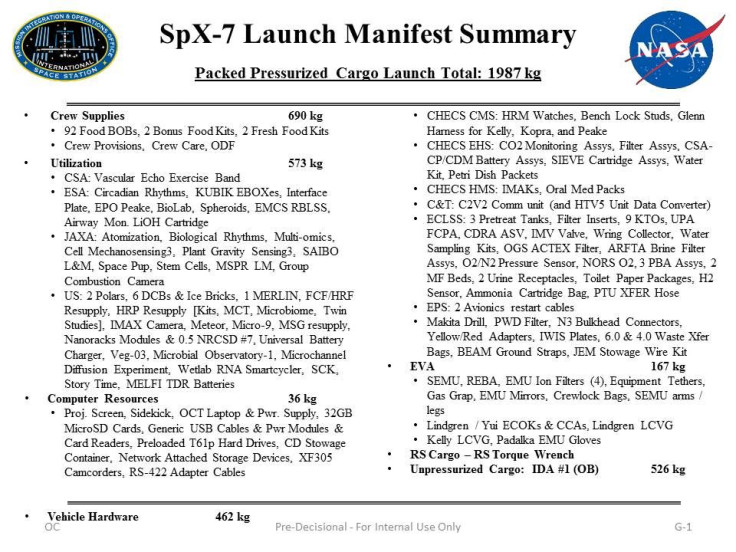

A full list of the supplies that were on board the rocket, provided by NASA, is below -- “IDA” stands for “International Docking Adapter” which was packed into the unpressurized cargo hold. The load also included eight satellites sent by Planet Labs, a San Francisco-based company that is seeding space with camera lenses to provide high-definition imaging for industries such as agriculture and natural resources.

Sunday’s flight also carried 51 science experiments booked through NanoRacks by NASA’s National Design Challenge and the Student Spaceflight Experiments Program organized by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Six of those experiments had already been re-booked from the failed Antares flight in October. It costs $15,000 for a group of elementary students to send a basic experiment to the space station and $35,000 for high school or university students to send a slightly more complicated one. Most students throw fundraisers or apply for grants to pay to cover the costs.

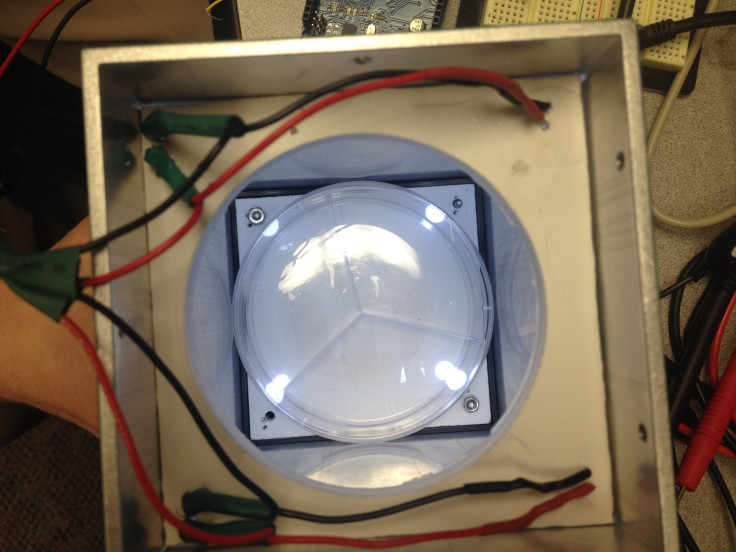

Kathy Duquesnay, an eighth-grade science teacher at Duchesne Academy in Houston, had worked with students for an entire school year to build an experiment that would study how the growth of a pea plant was affected by exposure to different colors of light. After their experiment blew up in the Antares launch, a small group of students stayed late after school to rebuild it in time for the Falcon 9 launch. She was watching the liftoff at Cape Canaveral with a fellow teacher who was also re-booked onto SpaceX after her students’ experiment also perished in the Antares flight.

“It was too high in the sky for us to realize there was a problem until we went back into the briefing room and then we realized, ‘Oh my goodness-- it blew up again. What are the odds?’” she says.

Patricia Mayes, director of NanoRacks’ educational program called DreamUp, says the company is contractually obligated to re-send experiments to space if students rebuild them at their own expense. Patrick O’Neill, marketing and communications manager at NASA’s Center for the Advancement of Science which coordinates the National Design Challenge, added that the agency would work hard to re-book the experiments on future flights, though he was not yet sure whether they would be able to do so.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.