Sprout Pharmaceuticals CEO Talks 'Female Viagra' Controversy, Additional Alcohol Studies, Addyi's U.S. Roll-Out And Global Ambitions

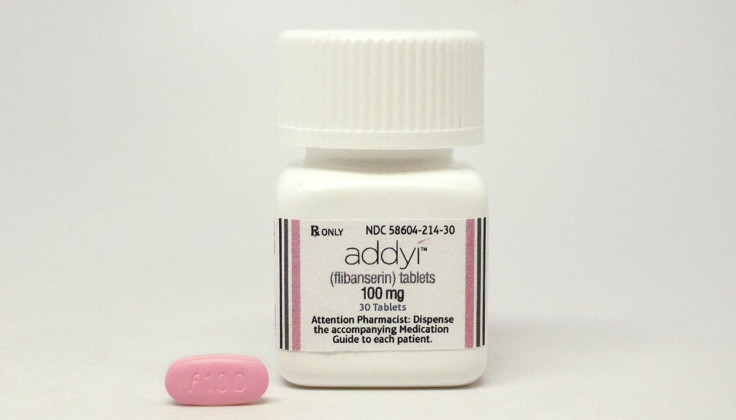

This week’s FDA approval of Addyi set the stage for a small biotech company to lead the charge toward commercializing one of the most highly-anticipated and controversial drugs of the year. Addyi is the first drug to tinker with sexual desire of any kind in men or women. Its maker, Raleigh-based Sprout Pharmaceuticals, has pledged to launch the drug nationwide for premenopausal women by October 17.

The company estimates that as many as 16 million American women of all ages suffer from the form of low sexual desire that Addyi will treat, called hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). HSDD is a sudden drop in sexual desire that cannot be explained by any obvious psychological or relationship issue such as stress or boredom with one’s partner. Addyi is thought to work in a manner similar to an antidepressant by adjusting levels of neurotransmitters including dopamine and serotonin that are associated with pleasure and reward in the brain.

The drug’s debut was twice delayed by FDA rejections based on the drug’s modest efficacy and safety concerns. Some critics are still not convinced that the benefits of the once-daily pill outweigh its risks. In large clinical trails, some women who took Addyi experienced dizziness (11 percent), sleepiness (11 percent) and nausea (10 percent).

Supporters say those side effects are no more severe than the side effects that people already experience from Zoloft or Prozac, or which men endure for the convenience of Viagra. But a few subjects in a small trial of mostly men also showed a severe drop in blood pressure after consuming alcohol and taking Addyi. Some even fainted.

Concerns over this risk in particular prompted the FDA to recommend that women who take Addyi abstain from alcohol and require Sprout to roll out a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) to closely monitor the drug’s real-world use. The agency will also make physicians and pharmacists to become certified by the company before offering it to patients.

Valeant Pharmacueticals announced Thursday that it is buying Sprout for roughly $1 billion. Sprout’s CEO Cindy Whitehead spoke with International Business Times late Wednesday about why the drug has garnered so much attention and scrutiny, and what’s next for her team.

International Business Times: Why did you choose the name Addyi?

Cindy Whitehead: It just embodied, I think, the mission and that was a woman’s best sense of self. Addy became our role model, if you will, for women on their own terms. That’s what meant so much to all of us, is that finally women were going to have the option to make the decision for themselves with a healthcare provider around the most common sexual dysfunction.

IBTimes: Sprout told the FDA in June that the company would voluntarily hold off on direct-to-consumer marketing for Addyi such as radio and television advertising for 18 months after its approval. Why did you make this offer, and what concerns were you trying to put to rest in doing so?

Whitehead: We know how much public interest there is in this medication. We wanted to make sure that the marketplace was educated so healthcare providers and pharmacies understood the risk profile of Addyi. Ultimately, consumers are better informed if you go forward with the intermediaries who are going to be having a conversation with them.

The spirit is let’s just put responsible education into the marketplace first before we go to any form of advertising. That’s what we’re doing now with this REMS program and certification for healthcare providers or pharmacies. They’ll go online to addyrems.com and go through a slide deck that walks them through the drug. They’ll take a knowledge assessment and then they’ll be certified to prescribe Addyi. It’ll take less than 10 minutes for them to go through it but we’re still making sure there’s that discipline of educating first.

IBTimes: The FDA has directed Sprout to conduct additional tests that more closely examine the interaction between Addyi and alcohol. What will these studies specifically measure, and when do you expect to have results?

Whitehead: We’ve already given them draft protocols. We’ll work with the FDA to agree on protocols and then go forth and do the studies.

What we know about Addy is that in the phase three approval trials, alcohol was allowed and the number of women who called themselves mild to moderate drinkers was in line with the population. What we weren’t doing was monitoring daily alcohol intake to know, if they had a side effect -- was it related to if they had alcohol that day? We did a challenge study in which they drank two to four shots of grain alcohol in 10 minutes and then dosed Addyi and that’s where we saw the increased instance of hypotension and syncope, and that’s why we have the warning related to it.

Contraindication of alcohol was the cautious place to be for this until we gather more data. The studies are both another challenge study with women and also looking at real world alcohol intake -- so a couple glasses of wine likely with dinner, they go to bed a couple hours later at bedtime, and we monitor vitals overnight. It’s likely to take a year to go forth and do that kind of work.

IBTimes: One of the main points of criticism about your data supporting the safety of Addyi has been the design of the Alcohol Challenge Study to measure the interaction between high doses of alcohol and the drug. Only two out of 25 patients enrolled in that study were women. Why didn’t you test the drug's reaction to alcohol in more women?

Whitehead: I think part of that is people don’t understand the nature of drug development. You do large pivotal trials in target populations and you want to make sure they’re reflective of the general population. When you do challenge studies, you recruit healthy volunteers. They know they’re entering into a trial, they consume this much alcohol and would qualify and they want to participate.

In all candor, we didn’t see many women interested in participating. We hadn’t really anticipated that outcome and that’s why we’ve committed to re-do it with women. So we’re going to work to recruit women specifically who could tolerate that kind of alcohol or would characterize themselves as that type of drinker into a trial.

IBTimes: You have a staff of 34 today but have said you will be ramping up in anticipation of the drug’s launch. How will you prepare for the rollout of Addyi nationwide?

Whitehead: We’ll grow deliberately. We’re going to go to 200 salespeople. We’re in the process of hiring them and we’re going to cover those folks who already understand this condition and are seeing these women every day. Predominantly ob-gyns is where this conversation is coming up, and with some primary care physicians and some psychiatrists with a particular interest in sexual health. I think that we’ll see what the market dictates.

Our mission has been from the outset, provided we have the data that characterizes the risk and benefit -- women deserve access to a medical treatment for a medical condition. What I’d like to see happen as we enter into this next chapter is that we allow as many women to have access to that as are appropriate for treatment and that beyond the US, after opening the door here, that we ultimately get to do this for women globally.

IBTimes: A recent Associated Press story pointed out that you received an FDA warning letter while at Slate for making false and misleading statements about a testosterone implant for men called Testopel. What did you learn from that experience and how will you avoid the same missteps with Addyi?

Whitehead: We worked in cooperation with the FDA to correct the information. It was our very first sales aid as a company. The process is they don’t proactively approve materials --they have them and can reactively go back and say, ‘We take issue with these items.’ They did in our case. We corrected it. I think we’re not unlike any other drug company that has received a letter, in that regard. You take the corrective actions that they ask for.

We work with the FDA. We’ve thought through so many things with them in this process, including how we appropriately educate a marketplace, how we go out conservatively. That’s our intention here.

IBTimes: Are there any misunderstandings about Addyi that you want to clear up?

Whitehead: I would just say, I think we should all wonder why there’s controversy here. I think that at the end of the day, benefit and risk is a subjective assessment. If we assign no value to the benefit that women are receiving from this treatment, then we paint this picture very differently. I think women get to decide what the benefit is and what risk, for them personally.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.