Ultra-Black Feathers On Birds Of Paradise Caused By How They Scatter Light

With the general exception of humans, among whom the female form is often considered more aesthetically pleasing than males, it is usually the male members in other species — especially birds — who are more eye-catching than the females. The peacock, strutting about with its tail fully fanned out, is the most obvious example.

When it comes to plumage, some species of birds of paradise are remarkable, featuring the blackest black that nature has to offer. The sheer blackness of the feathers makes the other colors on them seem like they are glowing. Of course, this sort of plumage is only found among the males, something they use to their advantage in their courting rituals when trying to woo mating partners.

The dazzling display of colors, as seen against that black background, is a juxtaposition that amounts to something like an optical illusion for both other birds and humans, as for all vertebrates, even though the display is meant for female birds of paradise.

Dakota McCoy, a Yale University graduate now at Harvard University, was the co-lead author of the study. In a statement Tuesday, she explained the phenomenon: “An apple looks red to us whether it is sitting in the bright sunlight or in the shade because all vertebrate eyes and brains have special wiring to adjust their perception of the world according to ambient light. Birds of paradise, with their super-black plumage, increase the brilliance of adjacent colors to our eyes, just as we perceive the red even though the apple is in the shade.”

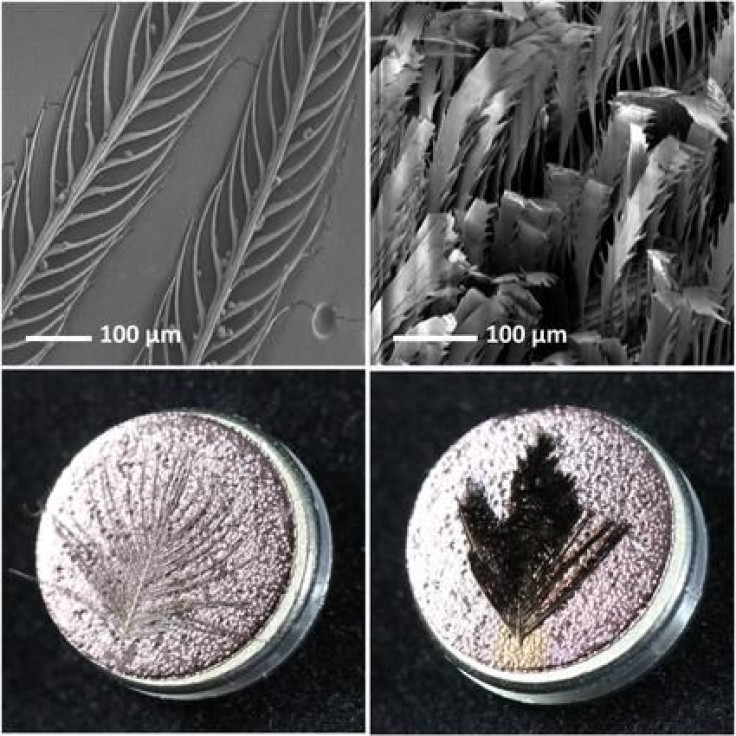

Feathers of these birds — five species of birds of paradise — appear super-black because of how the internal nanostructure of the feathers absorbs and reflects light, a new study has found. These feathers absorb as much 99.95 percent of all light falling on them, giving them their velvety, ultra-black look, which is at par with best light-absorbing man-made materials such as the lining used in space telescopes.

The microscopic internal structure of the feathers is also much the same as the materials designed by engineers for improving light absorption by solar panels.

“Evolution sometimes ends up with the same solutions as humans,” Rick Prum of Yale, a senior author of the study, said in the statement.

Since the super-black property comes from the internal structure of the feathers, and how that affects scattering of light, the feathers appeared black even when they were coated with gold, the researchers found.

Also, the ultra-black plumage is particular to birds of paradise that are involved in mating displays, with the feathers of the others showing a microstructure that did not allow for the same amount of structural absorption of light.

“Sexual selection has produced some of the most remarkable traits in nature. Hopefully, engineers can use what the bird of paradise teaches us to improve our own human technologies as well,” Prum said.

The other co-lead author of the open-access study, titled “Structural absorption by barbule microstructures of super black bird of paradise feathers,” was Teresa Feo of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The study appeared in the journal Nature Communications.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.