Understanding 'Her': Experts Ponder The Ethics Of Human-AI Relationships

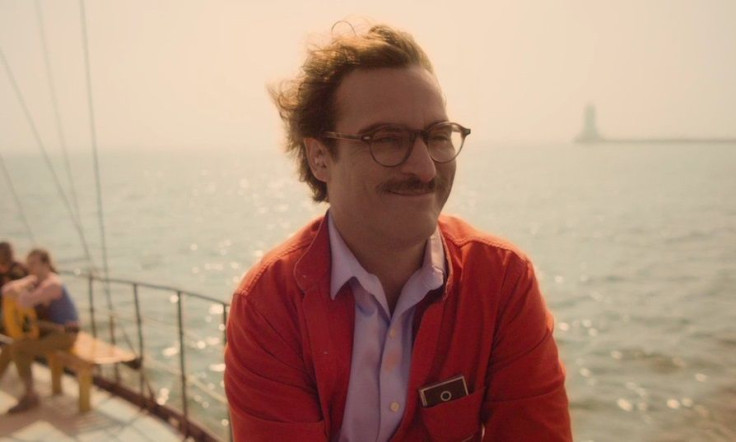

Samantha, a fictional operating system in Spike Jonze’s movie “Her,” is a seductive poster child for artificial intelligence. She purrs in your ear with the dulcet tones of Scarlett Johansson, she organizes your emails and calendar for you and she completes that book proposal you’ve always been meaning to finish. And if you’re a sad yet sensitive soul, like Joaquin Phoenix’s Theodore Twombly, she can supply original romantic music compositions, and steamy phone sex.

Still, the idea that a super-intelligent bodiless computer would seek romance with a squishy glorified primate seems sort of odd. Would an AI really be able to make a deep emotional connection with a being who thinks millions of times more slowly than it does, and who lives such a radically different existence from its unbounded, silicon and fiber-optic universe? Think of it this way: Could you really fall in love with an amoeba -- even if it was a sensitive, soulful amoeba?

Though it's true AI is still a distant dream, experts are already pondering its potential impact on humanity. Even AI far less sophisticated than Samantha's could engender some serious issues, says Kate Darling, an intellectual property researcher at MIT’s Media Lab who is also on the forefront of robo-ethics. One-sided love affairs are more likely, at first. A man of Twombly’s type might be enthralled by Siri 2.0 -- but she’ll only ever give polite quips and Google Search results in return.

“We’re going to be able to fall in love with AI long before it is able to fall in love with us,” Darling says.

Issue 1: How Close Are We To AI, Anyway?

"Her" is set in a safely near future -- just hazy and weird enough to seem different, yet not outside a present-day viewer’s lifespan. And likewise, most predictions -- by experts and amateurs alike -- place the advent of truly self-aware artificial intelligence in the realm of “just around the corner,” according to Stuart Armstrong, an Oxford University philosopher who works at the Future of Humanity Institute.

Armstrong has been analyzing hundreds of AI predictions (he posted an initial write-up of his findings at the blog Less Wrong), and has found little difference between timelines hazarded by experts and non-experts.

“The most common prediction is 15 to 20 years from when the prediction is being made,” Armstrong says.

One problem in trying to pin down a timeline for the development of AI is that the goalposts for what constitutes true “intelligence” keep moving. It’s harder and harder to identify the features that you could call uniquely human. Behaviors that we thought could only be accomplished by humanity turn out to be within the reach of computers, and start to look less like intelligence and more like database processing.

“No one knows what the problem is, so we have no clear idea how to solve it. You’re talking about an entity that has never existed in human history,” Armstrong says. “If you told people 10 or 15 years ago that we’d have a computer that could win on ‘Jeopardy,’ they’d say that AI is solved -- and it’s not.”

Issue 2: How ‘Human-Like’ Would AI Be?

We humans prize our humanity, and we love to project it onto everything from puppies to household appliances.

“Even those of us who work with robots every day and know they’re not real tend to anthropomorphize them,” Darling says. “We’ll think that they’re cute, give them a gender, or ascribe intent and states of mind. It’s something we like to do.”

But there’s little reason to expect that true AI would bear any resemblance to a human personality. Most AI in fiction -- from "2001: A Space Oddity"’s HAL 9000 to any number of B-movie robots -- are made by humans, for humans.

“Every single AI that’s ever been in any movie is a human,” Armstrong says. “The evil ones are generally emotionally repressed humans, while the good ones are generally affectionate saints. All of these fall within the very narrow bounds of humanity.”

The reality of AI might be something wholly alien. A bodiless program like Samantha might have a fairly different notion of her individuality, since she can be copied from one device to another, or connect with other operating systems online. How could one maintain a cohesive whole?

“They may have no sense of self-preservation,” Armstrong says. “They might see that they should probably stay alive to accomplish their goals, but beyond that … they may be perfectly willing to overwrite themselves.”

So what form might love take in an entity with no sense of self, and no sense of mortality (plus no need to procreate)?

Issue 3: Danger, Theo Twombly, Danger!

The risks of AI love in the real world may go beyond heartbreak. Darling points out that some thinkers, like MIT colleague Sherry Turkle, worry that people may start preferring relationships with AI to relationships with people.

“I, personally, am more concerned with this technology falling into the wrong hands,” says Darling -- and she means hands of both of the corporate and government kind. A super-intelligent operating system in everyone’s ear carries equal possibilities for surveillance and advertising.

“If you can get a child to become friends with a robotic toy, that toy could start manipulating that child,” Darling says. “Or what if Samantha is telling [Theo] all the time that she loves Coca-Cola?”

Entrusting AI with power over our lives could also turn into a classic “monkey’s paw” scenario. Like a fairy tale genie, an AI personal assistant may end up technically granting your wish or fixing your life, but in a way that makes you wish they hadn’t bothered.

For instance, if an artificially intelligent personal assistant understands that part of its job is to ensure that you are sexually satisfied, “the simplest solution might be just to castrate you, if they see that this is going to result in less sexual dissatisfaction,” Armstrong says.

An AI, unburdened by human scruples, may end up favoring the most direct path to a solution. And, from a computer’s point of view, a lot of our everyday problems could be quickly solved by murder -- or suicide.

“If we program AI badly -- if the definition of 'success' is that we say we’re happy with their performance, then they’re motivated to lobotomize us in whatever way is most practical to confirm that their performance is good,” Armstrong says. “Whatever simple goal we give them to organize our lives generally has a possibly pathological solution.”

Issue 4: Who Cares?

Whether or not artificial intelligence will “really” love us may be beside the point; humans will still feel for them just the same.

Even between humans, “a lot of the love we experience is one-sided,” Darling says. “We love for very selfish reasons.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.