Unicorn Workers Could Become Overnight Millionaires Under Law That Eases Restrictions On Private Shares

SAN FRANCISCO -- Stuck on the 1,269th page of a 1,301-page bill in Congress concerning the future funding of American highways is a measure that could reap major rewards for tech unicorn employees. It’s a proposal that may make it easier for workers to cash out their holdings in companies like Uber, Dropbox and Airbnb without having to wait for an initial public offering.

The earmark is stuck near the end of a major $305 billion highway bill negotiated by lawmakers earlier this week. It was passed by the House on Thursday and is expected to be passed by the Senate before the Friday deadline. The White House has also said that President Barack Obama will sign the bill. Though the measure is an afterthought in the grand scheme of things, it is expected to have a big impact on the lives of Silicon Valley employees working for major companies that have yet to go public.

In essence, the bill deregulates the trading of private shares, making it faster for individuals to sell their equity to investors. Though this change comes with restrictions, many in Silicon Valley expect the bill to benefit top employees who want to liquidate their holdings and use the cash to pay off student loans or buy houses in the Bay Area’s expensive real estate market.

“Equity is the currency of Silicon Valley, of San Francisco, of the technology industry. The problem with equity for people who live in the city or in Silicon Valley -- very expensive places -- is that there is no liquidity,” said Nancy Yamaguchi, a partner at Withers Bergman LLP. “They can’t turn that into cash so that they can pay the high rents in San Francisco.”

Currently, employees at private companies are barred from selling any of their equity without waiting 12 months after converting their options into restricted stocks. Under the new measure, employees will be able to sell in just three months, either to prospective outside buyers or their own companies.

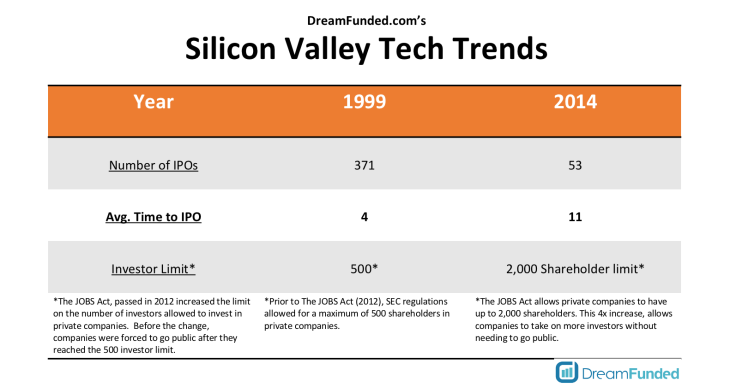

Just a few years ago, this legal change was not necessary, as private companies waited only about four years on average before going public and giving their employees a chance to cash out. But since the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act of 2012, which made it possible for startups to sell equity to a larger pool of investors, private tech companies now wait an average of 11 years ] before taking their companies public.

“If you’re someone coming out of engineering school and working for a startup, you don’t have seven to 10 years to make substantial money and pay off your debt,” Yamaguchi said.

The hope is that this bill will make it possible for more employees, especially those of high-valued private tech companies, to liquidate their holdings and pump more money back into the economy. “If you have an abundance of employees who are able to sell their shares, they’ll start unlocking millions of dollars in this economy,” said Manny Fernandez, CEO and co-founder of Dreamfunded, an angel investment platform.

“New houses [and new cars] will be bought and everyone will be a beneficiary of this unlocked capital that’s been held for many years,” Fernandez said.

The downside, of course, is that a law that could create thousands more newly minted millionaires in the Bay Area almost overnight could put more pressure on the area’s already limited housing stock – possibly forcing more working class individuals and families even farther away from their jobs and schools.

The wording of the measure is the same as that used for the Reforming Access For Investments In Startup Enterprises Act, otherwise known as RAISE. That legislation was introduced earlier this year by U.S. Rep. Patrick McHenry, R-N.C., and passed the House unanimously in October.

“Secondary markets are among the most important arenas for entrepreneurs seeking capital, but the lack of liquidity in these markets has limited their viability as a tool for growing companies,” said McHenry when he introduced the bill in April. “My bill is a narrow and straightforward fix.”

Show Us Your Numbers

But several experts remain skeptical of RAISE and question the overall impact it can actually have. The reason is that the change comes with several notable limitations.

Chief among them is the requirement that sellers provide potential buyers with key financial documents from their companies. That means recent balance sheets as well as profit and loss statements, both of which must adhere to generally accepted accounting principles. That's information that many startups don't keep, and those that do are usually companies that intend to go public and don't want to disclose such details.

“Why show your competitors, why show your customers, all of that information about your finances?” said Timothy Harris, partner at Morrison & Foerster LLP. “I think that’s going to kill a fair number of these transactions.”

Additionally, many companies use their shares and the promise of an upcoming IPO as a way to retain talented employees -- a difficult prospect in Silicon Valley’s ultra-competitive hiring environment. By failing to provide this required information, tech companies could essentially block transactions and force their employees to stick around, at least until they go public.

What's more, sale of private shares will also be limited to accredited investors, who are individuals with a net worth of $1 million or those who earn more than $200,000 per year. The term accredited investors “is a synonym for rich people,” Harris said.

A Step In The Right Direction?

However, there will likely be situations where the changes can benefit both employees and their companies, said Vincent Bradley, CEO and co-founder of FlashFunders. For example, Bradley described a scenario where a key employee at a major company might approach her firm and ask for approval to sell shares so she can buy a home in San Francisco -- a market where the median home price is now more than $1.1 million, according to Zillow.

The employee could ask for a list of investors the startup would be comfortable selling to, Bradley said. The company, in this instance, would likely have more incentive to provide the necessary documents rather than anger its employee and drive her off to a competitor.

“And if the company is doing well, most likely venture capitalists will jump at the opportunity to buy more,” Bradley said. “And then it’s just about finding a price point that keeps the employee happy but is also good for the company.”

Companies that wish to avoid going public could also use RAISE as a way to lure in candidates, establishing a trend of helping facilitate the sale of private shares as a way to show potential hires that they provide a realistic path to liquidity.

“What this piece of legislation does is it really provides different liquidities for the employees, for the founders, for the executives, without all of those liabilities, exposure, and costs and burdens of being a public company,” Yamaguchi said.

As for investors, the requirement to provice financial documents is a big win as it will give them a better of idea of what they are getting into if they decide to buy stock from an employee working at a company like Snapchat or Pinterest.

Investors are “going to have information about the company directly from the company, so it’s going to allow them to better evaluate the price that they’re willing to buy the shares at,” said Pamela Greene, a securities lawyer at Mintz Levin.

Despite these limitations, most experts generally agree that RAISE is a step in the right direction in terms of giving tech employees a better, quicker path toward liquidity.

“Little by little, they chip away at these laws,” said Kendall Almerico, a business and crowdfunding attorney with the law firm DiMuroGinsberg. “Once the Securities and Exchange Commission feels comfortable that this isn’t going to cause a lot of problems, that’s when the door can keep opening.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.