US Child Poverty Rates Are High; Blame Large Population, Government Mistrust, And Fear Of More Entitlements; The United Kingdom May Have Answers

The United States is considered the richest, most economically competitive country on the planet. So how is it possible that it also has one of the highest rates of child poverty in the developed world?

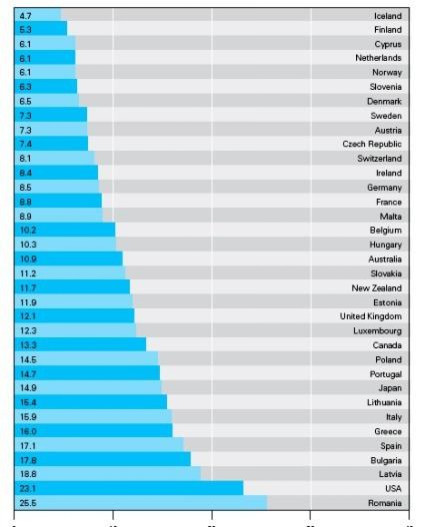

In recent years, international surveys have concluded that the U.S. leads the pack when it comes to the number of children living in impoverished conditions among industrialized nations, at nearly 16 million. Even when considering percentages, not absolute numbers, only Romania had a higher rate than the U.S. (25.5 percent versus 23.1 percent) of child poverty among developed countries in 2011, according to the most recent analysis of relative poverty from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). One American child in four is, relatively speaking, poor. That's a disheartening and surprising outcome for a country that generates close to 30 percent of the world’s GDP.

The U.S. also has a higher rate of child poverty than overall poverty, which is by no means the norm in developed countries.

The Economic Policy Institute reported the overall relative poverty rate of the U.S. was above 17 percent, the highest among developed nations in the late 2000s. But other countries with comparable rates still had a considerably lower percentage of children in that category.

For instance, while Australia had an overall relative poverty rate of about 14 percent in 2009, its child poverty rate per capita was 10.9 percent. European countries such as Germany, Finland, Slovenia and Norway also had slightly lower child poverty rates compared to the overall population. Part of the reason is that those nations are not as large, nor as demographically diverse, as the United States.

“It’s easier for places like Luxembourg or Sweden to score better because they’re so much smaller,” explained Chris de Neubourg, the head of social economic policy at UNICEF’s Office of Research, noting it is inherently harder to implement wide-reaching social safety net initiatives to alleviate poverty in the U.S. because of how much power state governments have in organizing those programs.

Then, there's the issue of what metrics to use to define who's poor.

The U.S. government uses absolute poverty figures (meaning, the number of people who can barely purchase basic necessities like food and clothing) when calculating its official poverty rate, which clocked in at 15 percent of the country (or more than 46 million people) in 2010.

The UNICEF numbers compare relative poverty between industrialized countries (meaning, the number of people with incomes below the general standard of living in their country) in order to determine the percentage of children living in households with incomes below what in "normal" in their own societies.

The Economic Policy Institute defines relative poverty as the number of households with income below 50 percent of the national median (in the U.S., $50,054 in 2011). As a result, in the U.S. the relative poverty rate of 17.3 percent in 2010 was higher than the official poverty rate.

Unemployment, Welfare Reform, Prison: How the U.S. Rate Became So High

Methodologies aside, cultural and geographical factors may be at play too. With a sprawling population equivalent to about half of the European continent’s and a culture that fiercely celebrates self-reliance -- and even suspicion of government -- the U.S. faces several challenges in alleviating its epidemic of poverty.

It’s not that lawmakers aren’t aware of the problem. As anyone who followed the recent presidential election can recall, poverty reduction – among children, the elderly, minorities and pretty much every traditionally “vulnerable” population – was an enormous focus of the debate between Democrats and Republicans. But the two parties have completely different ways of looking at the problem and neither is in the mood to compromise.

While Democrats tend to push for strengthening social safety net programs as a means of aiding struggling families, especially in post-recession America, conservatives have shunned the idea of additional government spending. Instead, they have generally focused on lowering the nation’s stubbornly high unemployment rate to combat the problem.

That isn’t completely misguided, since unemployment is logically one of the largest contributors to poverty and as a result, child poverty, according to Dr. Curtis Skinner, the director of Family Economic Security at the National Center for Children in Poverty.

“Unemployment may be the biggest part of the picture. The rate of child poverty went up sharply after 2006 and as you can see, even after the Great Recession we’re still stuck at 8 percent,” Curtis said, referring to the current national unemployment rate.

The lowest recorded child poverty rate was in 1969, when about 13.8 percent of American children were counted as poor. But while that can be attributed to a strong labor market and economy and low unemployment rate, Skinner said some of the credit should also go to the creation of President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” initiatives in the mid-'60s. In addition to significantly increasing and expanding Social Security benefits and coverage, those initiatives included the Food Stamp Act of 1964 (which expanded the federal food stamp program), a historic investment in public education, and the creation of Medicaid.

Several factors contributed to rising poverty, particularly child poverty, within the last decade – like the growing number of single-parent households. Almost half of all children in those homes were poor in 2011, according to the non-partisan Congressional Research Service, which reports the number of children in single, female-headed homes has doubled since the overall child poverty rate was at its historic low.

A shift to tougher penal policies that emphasize longer prison sentences is also credited with the high poverty levels among African-American households, who comprise about 13 percent of the population. Approximately 40 percent of black men in their 20s and early 30s who do not have a high school diploma are behind bars, leading to a mounting number of families led by single women – who, as previously noted, are already more likely to be poor.

Although the overall poverty rate declined during the 1990s, a period of economic vitality within the U.S., the passage of the 1996 welfare reform legislation gutted benefits allocated to poor children in single-parent households.

“The share of poor children in single female-headed families receiving cash aid is well below historical levels. In 1993, 70.2 percent of these children’s families received cash aid. In 1995, the year prior to passage of sweeping welfare changes … 65 percent of such children were in families receiving cash aid,” reports the CRS, noting that only about 25 percent of those households received government cash aid in 2010.

According to Skinner, a focus on macroeconomic policies designed to boost employment for lower-skilled workers -- he mentioned President Barack Obama’s proposed American Jobs Act as a good example -- would be the ideal way to combat child poverty. But he still said government intervention cannot be discounted, pointing to the United Kingdom as an example of how government can play a real role in improving conditions for low-income families.

A Case For Government Intervention, Brought To You By The UK

In 1999, Prime Minister Tony Blair made a remarkable pledge to eradicate child poverty across Britain, a commitment that the Conservative government currently in power has promised to uphold.

“I can tell you the UK has improved its position substantially,” De Neubourg said, mentioning how the country’s rate of poor children has declined even during the recession. “Whether or not that will be sustained by the new government is unclear, but it shows that government interventions can have a positive effect.”

When Blair made his pledge, one in four children in the country, or 3.4 million, lived in poor households. Ten years later, absolute poverty had fallen by half, while relative poverty (in the UK, those with incomes at below 60 percent of the national average) dropped 15 percent. It’s a sharp contrast from the U.S., where the financial crisis and resulting recession led to the highest rate of child poverty in 20 years.

Britain's anti-poverty initiatives focused specifically on raising incomes for families with children, whether or not the parents were currently employed. In addition to raising the nation’s universal child benefit tax credit, the government also created a new children’s tax credit to assist low- and middle-income families. The introduction of the country’s first minimum wage, combined with tax credits for low-income workers and their employers, helped reduce lone-parent employment by 12 percent between 1997 and 2008, according to a 2010 report from the Foundation for Child Development.

The country also made huge investments in early childhood education, including universal pre-k, which studies have demonstrated are essential in reducing the risk of poverty being passed on from one generation to the next. James Heckman, a conservative-leaning economist who has done extensive research on early childhood education, said investments in that area results in payoffs such as reduced crime, reduced health care costs and higher future earnings.

In early February Heckman told The Washington Post the benefits of those programs in the U.S. “would outweigh the costs.”

With that in mind, President Obama in his recent State of the Union called for the creation of universal pre-k programs across the nation. The proposal is already expected to face deep opposition in Congress, where education funding could be gutted in the event of the possible sequester in March.

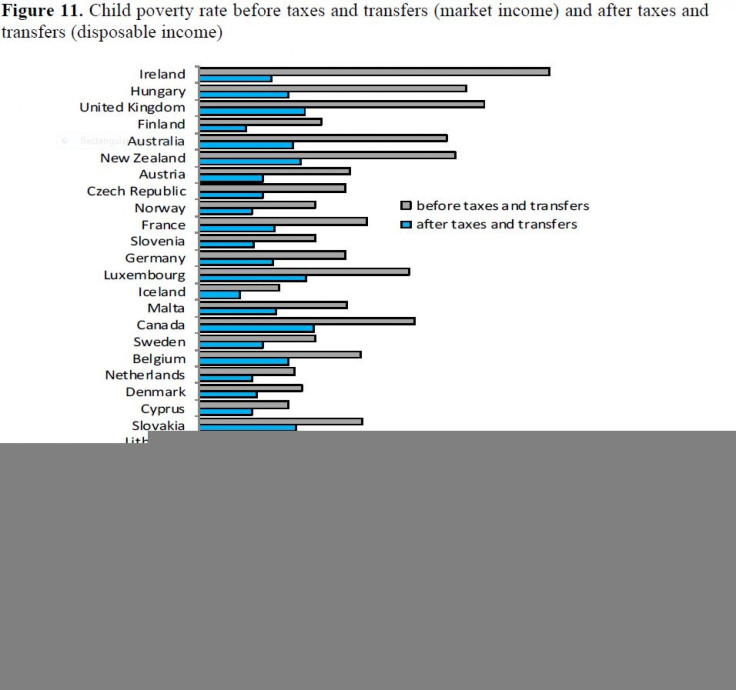

One thing is clear: Nations with strong social protections in place for children and the poor have been the most successful at reducing their child poverty rate.

While social protections may not reduce the overall poverty level, they are extremely effective at protecting the population from poverty generated by labor forces alone, according to a 2012 UNICEF working paper. The paper used country data that at least partially reflected the impact of the global economic recession.

“In absolute terms, state intervention reduces child poverty levels by more than 20 percentage points in Ireland, Hungary and the United Kingdom. But it also has notable effects in Austria, Australia, Canada, France, Germany and New Zealand,” states the report.

That is quite visible in Ireland, where the child poverty rate – above 40 percent – dropped below 10 percent after the impact of government benefits and tax breaks was calculated. In contrast, the poverty rate barely budges in the U.S. when those taxes and transfers are calculated.

UNICEF reports that countries that saw the most comprehensive reduction in poverty due to government assistance were those that spent at least 2 percent of GDP on family benefits and tax breaks. In 2009, the U.S spent less than 1.5 percent of its GDP on those areas.

U.S. Uses Outdated, Cold War-Era Formula To Measure Poverty

But before the U.S. can truly tackle its poverty problem, it may need to adopt an official poverty measure that wasn’t developed during the Cold War.

“One thing we seriously need to talk about is the rather primitive system used to measure poverty in this country,” Skinner said.

The official U.S. poverty measure was developed nearly half a century ago by just one analyst at the Social Security Administration. As a result, it reflects a notion of economic need based on a standard of living from the early 1960s, when food was a household’s largest monthly expense.

“The thresholds were derived from research that showed that the average U.S. family spent one-third of its pre-tax income on food, based on a USDA 1955 Food Consumption Survey. After pricing minimally adequate food plans for families of varying sizes and compositions, poverty thresholds were derived by multiplying the cost of those food plans by a factor of three (i.e., one-third of the thresholds were assumed to address families’ food needs, and two-thirds addressed everything else),” reports the Congressional Research Service.

The current poverty threshold in place, while adjusted for inflation, does not account for costs like medical expenses, transportation or childcare. It also does not consider cost of living differences by region, or calculate the impact of government subsidies and tax credits.

Meaning, a system initially created to track progress in alleviating poverty actually ignores the effect anti-poverty initiatives have on families’ economic well-being.

The U.S. Census Bureau in 2011 released a new Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) to account for modern cost-of-living expenses and federal anti-poverty measures. But the old system is still the “official” measure -- possibly because under the more accurate SPM threshold the poverty rate actually increases for the general population (In 2010, the official rate was 15.2 percent while the SPM rate was 16 percent).

But that’s not the case for children. While the poverty rate in 2010 increased for adults under the alternative measure, anti-poverty programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (food stamps) pushed the number of children in poverty from 16.8 million under the official measure to 13.6 million in the SPM.

By any measure, that’s still too high. And there are still a plethora of other issues, such as underemployment, low wages and health care costs – the SPM reveals unreimbursed medical expenses damage the economic well-being of the poor more than any other factor – that will continue to add to the problem if left unaddressed, even with an expansion of key programs currently in place. But it still demonstrates that social safety net initiatives can have a positive impact on improving the standard of living for millions of vulnerable children.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.