US-Led Anti-ISIS Coalition Is Running Out Of Airstrike Targets In Raqqa, 'Islamic State' Headquarters

The U.S.-led coalition killed roughly 30 Islamic State group militants with just one airstrike on the group’s Syrian headquarters of Raqqa on Friday. That was one of the heaviest single blows since President Barack Obama announced last year that the coalition’s air campaign would expand from Iraq into Syria. Before Friday, strikes over Raqqa had become sporadic and, sometimes, even ceased completely for weeks, making up only 3 percent of total coalition strikes since December, according to data compiled from daily coalition press releases.

The tapering off of airstrikes in Raqqa indicates that fighting the extremist group from the air alone is becoming more difficult, and calls into question whether it can be defeated without ground troops.

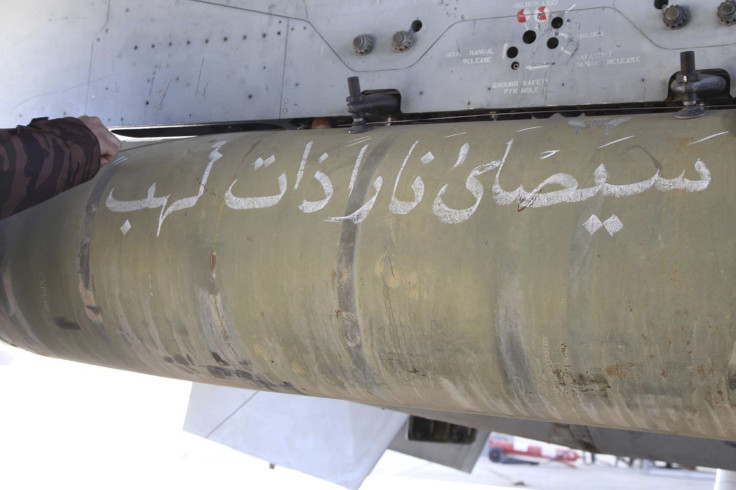

The first aerial bombardment in Syria, in September, had 18 targets in Raqqa, the city where the group also known as ISIS holds hostages, trains new fighters and governs the territory of its self-styled “caliphate.” That pace slowed down over the months, and of the 466 airstrikes in Syria since December, only 30 were near Raqqa. The coalition is running out of appropriate targets and militants have adapted to strikes, even learning to anticipate them. With limited targets and the recent withdrawal of the United Arab Emirates from the group of nations conducting airstrikes, Raqqa highlights the challenges of the air campaign in Syria designed, in Obama's words, to “degrade and destroy” ISIS.

“Raqqa is still populated. There’s some concern on the part of the coalition that hitting civilians is not a good idea,” said Dr. Ivan Eland, author of the "The Failure of Counterinsurgency: Why Hearts and Minds Are Seldom Won." “You do run out of targets, because this is an army rather than a terrorist group, but they’re still a primitive army and run and hide among civilians.”

The coalition’s Joint Task Force selects and approves each target using satellite data, information from drones and intelligence from coalition members to ensure that the “strike minimizes the potential for civilian casualties and damage to non-combatant infrastructure,” a spokesman for the Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve said. The process also adheres, he said, to international laws that prohibit “striking religious, cultural, historical institutions and medical facilities, among various other structures and civilian meeting places.”

“If you’re fighting from the air, you’re losing because you’re creating new terrorists,” said Eland. “You create more terrorists in response to the strikes. Even though the civilian casualties are by accident, the people are going to hold it against you. The best thing would be to have good local ground forces.”

The airstrikes have been more numerous in places where the coalition can coordinate with partners on the ground, as in Iraq, where the regular Iraqi Army, Kurdish peshmerga forces and local militias are fighting ISIS.

That is more of a challenge in Syria, where the only ground forces allied with the coalition (aside from Kurds in a few small areas) are the Free Syrian Army, commonly called “moderate” rebels.

FSA fighters provided intelligence to coalition air crews in Kobani, a Kurdish city on the border with Turkey that was the site of roughly 82 percent of coalition targets in Syria since December. Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) fighters were locked in a nearly four-month battle with ISIS in Kobani and, with the help of airstrikes, militants were successfully pushed out last month. That model has proven hard to replicate elsewhere in Syria, where “moderate” rebels are routinely suffering defeats at the hands of Islamist forces.

The air campaign in Syria also faces a lack of countries willing to participate in the actual bombing. More than 60 countries are members of the coalition some capacity, but only 12 have ever participated in airstrikes -- and this year, only three have flown alongside the U.S. The United Arab Emirates was originally part of the air campaign in Syria, but suspended airstrikes when Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kaseasbeh was captured Dec. 24. The U.S. Department of Defense and the Combined Joint Task Force both say the UAE remains a significant coalition partner, but refused to give any details on its contribution.

Unlike in Iraq, the Syrian government has not asked for the coalition’s help to fight ISIS, and many coalition members do not want to get embroiled in the nearly four-year long Syrian civil war. What’s more, in places like Raqqa, the risk of hitting civilians is much higher than average, as the city is completely under ISIS control. (When coalition forces did hit Raqqa on Friday, militants claimed the bombing killed an American hostage. There is no evidence to prove that claim.)

After releasing a gruesome video of al-Kaseasbeh’s execution on Tuesday, ISIS ordered all of its leaders to evacuate bases and move all prisoners out of Raqqa in preparation for airstrikes, according to the anti-militant activist group Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently.

“ISIS soldiers (are) trying to hide when it comes to coalition aircraft, but they’re not hiding like when the strikes began in September last year,” Abu Mohammed, one of the group’s founding members, told IBTimes via Skype. “As time progresses, they become accustomed to strikes and the timing. [Airstrikes] would not target the city and would focus on the empty headquarters.”

ISIS has been preparing for airstrikes since the coalition first targeted Raqqa. Militants moved their wives and children to safer suburban areas, avoided going out during the day and blacked out the windows of their vehicles. Elsewhere in Syria, the militants have been removing the ISIS flag from buildings and moving certain operations underground.

“These are primitive people, and the more primitive the enemy, the less the airstrikes are going to do against them. Even if they’re primitive technologically they can be very sophisticated in figuring out how to foil the airstrikes,” Eland said. “I knew these people were going to go underground and then you run out of targets. Then what do you do? Either you start hitting questionable targets or you have to find a ground force.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.