Watch: Bkav Researcher Beats Apple's Facial Recognition System

Just 10 days after the official release of Apple’s iPhone X, security researchers believe they have developed a method to defeat the device’s Face ID facial recognition system that was promised to be the next big step in security.

In a blog post and video published over the weekend, researchers at Vietnamese security firm Bkav laid claim to being the first to trick the iPhone X’s new biometric authentication feature into unlocking. While the method has yet to be replicated or confirmed by any other experts, it does represent the first apparent vulnerability in what Apple was hoping to be a bulletproof security feature.

The method used by the researchers to supposedly defeat Apple’s next generation of biometric security was decidedly low tech. Bkav’s team used commonly accessible materials to create a mask that was able to convince Face ID of its legitimacy.

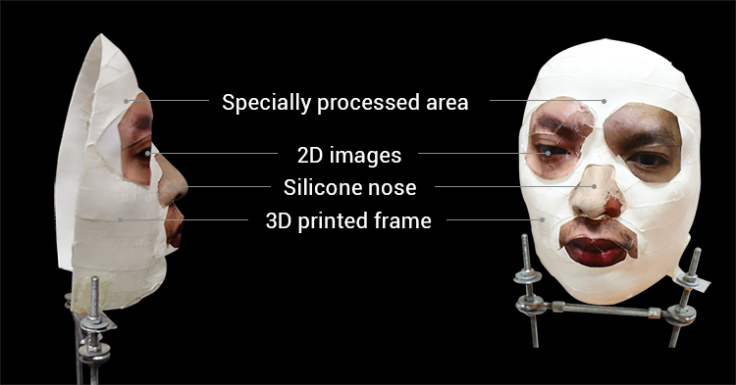

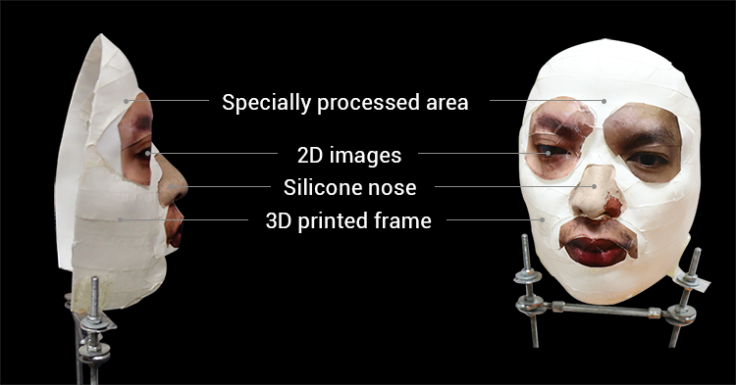

The mask consisted of 3D-printed plastic to create the frame of the face, silicone for the news, 2D paper cut outs of a person’s eyes and mouth and makeup for touch ups—all of which cost the researchers a total of about $150.

In a YouTube video posted by Bkav, the researchers show the mask in action. The group mounted the mask in front of the iPhone X, which they had sitting on a stand. As soon as one of the company’s employees removed a piece of cloth that was covering the mask, the iPhone X unlocked and allowed access just as it would if it recognized the owner’s face.

The demonstration, if legitimate, would present problems for Apple. When the facial biometric authentication method was first revealed on stage at an event held earlier this year, Apple’s Senior Vice President of Worldwide Marketing Phil Schiller swore the feature could not be fooled.

“The team has worked hard to make sure that Face ID can’t easily be spoofed by things like photographs,” Schiller said. “They’ve even gone and worked with professional mask makers and makeup artists in Hollywood to protect against these attempts to beat Face ID.”

Apple referred IBT to its knowledge base article about Face ID but declined to comment on the specifics of the research from Bkav.

The work published by Bkav suggests all of that testing may have been for naught—though there is plenty of reason to be skeptical of the potential hack, and plenty of questions left unanswered despite the security firm releasing a question and answer blog post regarding its research.

While Bkav shows the mask used to unlock the device, they don’t reveal much detail beyond that. Was the mask a mock-up of the person’s face that is recognized by Face ID or did they simply enroll the mask itself? Do details like the dimension of a person’s face matter, or does this suggest that all one needs is a template and printouts of a person’s eyes and lips to trick the sensors?

And then there’s the question of just how likely is this attack to actually affect anyone. Bkav’s researchers admit it is unlikely that the method would be viable to break into the average person’s device. Instead, it would require a much more targeted effort, likely against a high-profile person.

The researchers admit their technique would require detailed measurements or digital scan of a target's face. The researchers say they used a handheld scanner that required about five minutes of manually scanning their test subject's face. That puts their spoofing method in the realm of highly targeted espionage, rather than the sort of run-of-the-mill hacking most iPhone X owners might face.

“Time and effort were involved in creating the mask that fooled the Face ID recognition software. Detailed dimensions would have to be taken to create the mask, and the security firm alluded to the fact that they had to use a special material on the mask too,” Paul Norris—senior systems engineer for Europe, Middle East, and Africa at security firm Tripwire —told International Business Times.

Indeed, the process would require the type of exposure that one would expect from a celebrity rather than an average person. The researchers used a handheld scanner that required nearly five minutes of manual scanning of the test subject’s face in order to create the high-detailed printouts of the person’s eyes and lips. That is the type of detail one would be unlikely to get from an average person’s photos.

Terry Ray, chief technology officer of cyber security company Imperva, told IBT, “Nothing is 100 percent secure. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. The questions are: how much trouble would someone go to, and how much would they spend, to get your data?”

He said the attack laid out by Bkav’s researchers are “individual bespoke attacks” that would have to be built and executed against each victim separately, meaning it is only viable for targeted attacks against specific individuals.

Ray also noted that the attack would require threat actors to steal a person’s device and create the mask with such precision that it’s unlikely that a person may fall victim to such a scheme. Ray called it a “‘Mission Impossible’ style attack.”

It’s also worth noting that for Bkav’s demo to work, it would have to avoid triggering one of the several situations in which the iPhone X will prompt a user to enter their passcode rather than simply unlocking from a successful Face ID scan.

The iPhone X will ask its users to enter their passcode if the device has just been turned on or restarted, hasn’t been unlocked for more than 48 hours, hasn’t been unlocked via passcode in more than 156 hours, hasn’t been unlocked via Face ID in more than 4 hours, has received a remote lock command or has attempted five unsuccessful attempts to unlock via Face ID.

Ray said for Bkav’s mask attack to work the attackers would have to create the mask using photos, steal the victim’s iPhone, hope that it falls within the six-and-a-half day window in which a passcode isn’t required, make sure it doesn’t power down, and isolate it from all networks to prevent a remote lock command or other attempt to contact the device.

Then the attackers would have five attempts over the course of about 48 hours to get the mask to work, or risk getting prompted for the passcode that Ray said “ could take years [to crack] if the victim uses a six-digit alphanumeric code.”

Norris of Tripwire described the scenario in which a person is able to successfully execute the attack as “an unlikely sequence of events” and questioned if the attack is really even much of a threat to the average iPhone X user.

As unlikely as it may be for Bkav’s mask approach to ever be used in the wild to unlock an iPhone X, it does help to highlight some of the potential shortcomings of Face ID.

Josh Mayfield, director of product marketing at security firm FireMon, told IBT that Face ID “was never intended to be a security measure for strong authentication,” but rather a login method that makes life simpler for the user. “The hype around the automated log-in from staring at one’s phone was meant to give the user ease, rather than hardened security to prevent unauthorized access.”

Mayfield also said that Apple’s Face ID “seeks confirmation rather than disconfirmation” when authenticating a user. “When you begin with the goal of confirming, you will quickly squeeze every new variable to fit your desired outcome,” he said, warning that such systems will sometimes throw out details that are not “right” and instead focus on confirming the ones that are.

“The machine gets things close enough and uses probability to confirm the identity. But probability is not certainty,” he said.

Ray of Imperva said Face ID presents users with the ability to choose convenience over security but advised users who want to truly protect their device to use a passcode—at least until Face ID undergoes more rigorous testing to prove it can withstand attacks like those laid out by Bkav.

“For security [purposes], the best approach is a good six or more digit passcode of alphanumeric non-case sensitive characters,” Ray said. “For the rest of us, FACE ID is probably just fine.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.