What Keeps Animals Warm? Insulating Power In Animal Fur And Feathers Shows Radiation Plays A Role

Humans struggling to keep their homes warm in the winter could take some hints from the animal world.

The warm, thin furry coats of the Arctic animals were analyzed in a recent study which suggests that the animals use a form of radiative heat to stay warm. The findings, published in the journal Optics Express, suggest that hairs that reflect infrared light contribute insulating power – a phenomenon that can be used to develop new types of ultrathin insulation.

"Why do we need at least 60 cm of rockwool or glasswool" -- common types of building insulation made from minerals or glass fibers -- "to get a temperature of 20 degrees Celsius inside from about -5 degrees Celsius outside?" Priscilla Simonis, a researcher at the University of Namur in Belgium and lead author of the paper, asked. "Why is the polar bear fur much more efficient than what we can develop for our housing?"

The question stems from the fact that polar bears are able to insulate their bodies to 98.6 Fahrenheit during long, Arctic winters where the temperature drops to -40 Fahrenheit with an outside layer of fur that is only about two inches thick.

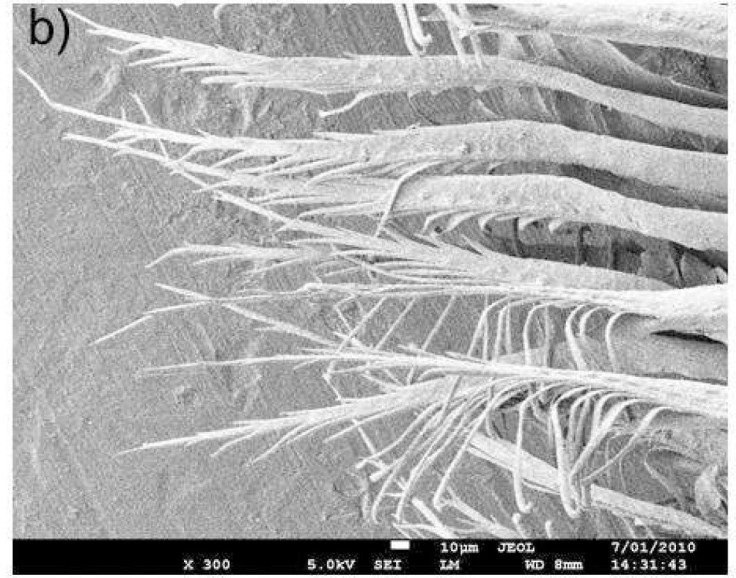

The research team came to their conclusion after studying the two different ways heat can travel – radiation and conduction -- and using experiments to see how they function with animal fur and feathers. The common belief is that animals keep warm with conduction, where a layer of air is trapped in the fur and slowly heated by the temperature of their bodies. The latest research shows that radiation may also be involved.

Researchers used computer models of a hot and cold thermostat – one representing the body heat of an animal and the other of a cold environment. The two were separated by air in an empty space. “Radiative shields” were added to imitate the hairs of a fur coat. Scientists found that the rate of heat transfer was dramatically reduced when the reflectivity of the radiative shields increased. The findings suggest the light scattering properties of animals’ coats diffuse thermal radiation to keep the animals warm.

In some cases, an animal’s white appearance belongs to the light scattering properties as a way to stay warm and hidden from predators. "This is particularly useful to animals, such as mammals and birds, that live in snowy areas," Simonis said.

The same model can be used to explain how “human clothes, rockwool insulators, thermo-protective containers, and many other passive energy-saving devices operate,” the authors write.

Simonis says the findings may lead to more advanced, thinner insulation.

"The idea is to multiply the interaction of electromagnetic waves with gray bodies -- reflecting bodies, like metals, with very low emissivity and no transparency -- in a very thin material," Simonis said. "It can be done by either a multilayer or a kind of 'fur' optimized for that purpose."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.