What’s In Your Nail Polish? Why Toxic Chemical Triphenyl Phosphate Remains In Cosmetics

Sunny Subramanian always reads the labels of nail polish bottles before applying glossy coats of shimmering pink or tangerine orange. The vegan beauty blogger in Portland, Oregon, says she watches out for toxic chemicals such as formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, and toluene and dibutyl phthalate, two materials linked to developmental defects.

“It makes sense to be as conscious about what we put on our bodies as we are about what we put in our bodies,” she said, adding that she often makes her own beauty products from scratch in lieu of store-bought versions. But Subramanian, who runs the website Vegan Beauty Review, said she wasn’t aware until last fall that triphenyl phosphate had joined the ranks of potentially worrisome ingredients in common nail care products.

The synthetic compound, known as TPP or TPHP, helps to boost the flexibility and durability of nail polishes by brands such as Sally Hansen, Revlon and OPI. It’s also used as a flame retardant in foam couch cushions, electronic equipment and other flammable objects. A growing body of early research suggests that TPP might be an endocrine disruptor, meaning it may tamper with human hormones, metabolism and reproductive systems when it enters the bloodstream.

The vegan blogger said she’s since sworn off TPP and won’t use nail polishes that contain it. Yet even as consumers grow more wary of TPP in everday products, in Washington the synthetic compound is facing a mixed fate.

President Barack Obama this week signed a landmark overhaul of U.S. chemicals regulations, which could bring heightened scrutiny to TPP as it’s used in furniture and other household items. But the rule changes won’t affect how the chemical is used in nail polishes and other cosmetics that line store shelves.

The split has to do with how federal agencies regulate consumer products and their ingredients. Under the newly reformed Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976, the Environmental Protection Agency can review and evaluate thousands of chemicals used in formulated, fixed-shape and other consumer products — from detergents, cleaners and varnishes to furniture, cookware and auto brake pads. Cosmetics, however, fall under the watch of the Food and Drug Administration, which has limited authority over the $60 billion personal care products industry.

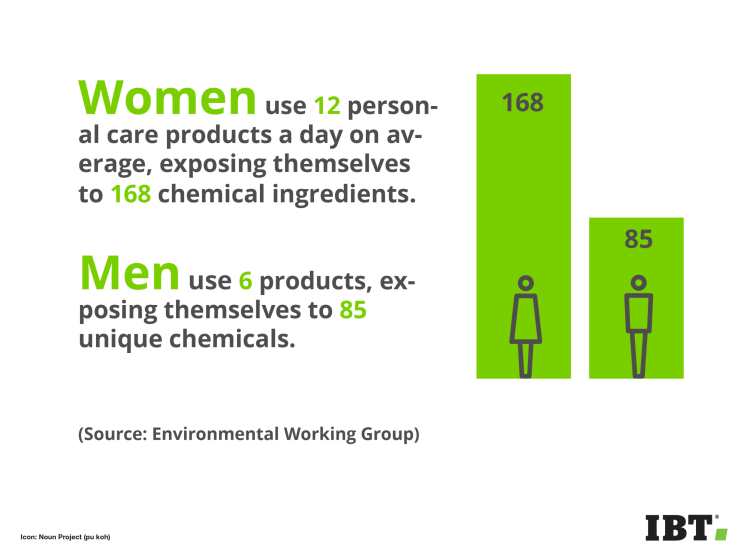

“The big issue is that cosmetics really aren’t regulated. The FDA’s hands are kind of tied,” said Melanie Benesh, a legislative attorney with the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization. “It’s so hard to know what’s in your products and what risks they pose.”

Product makers maintain that TPP is safe at the tiny doses used in everyday products and doesn’t pose a threat to human health. The chemical “has been widely and safely used across many industries around the world,” the Personal Care Products Council, a national trade group, said in a statement provided by email. “The nation’s makers of nail polish take great pride in their products’ long history of safe use.”

Reforms to the EPA’s 40-year-old toxics law could affect how TPP is used in sofas and other flammable products, if the agency later determines the chemical is hazardous. The outcome will have no direct impact on nail polishes and manicuring supplies, however. To regulate TPP in personal care products, Congress will need to adopt a sweeping reform of the FDA’s own outdated rules, legal experts said.

A bipartisan group of U.S. senators is already pushing for such a change. A Senate bill would transform the Great Depression-era law that governs cosmetics, toothpastes, deodorants, lotions and the multitude of personal care products we use each day.

Benesh said the FDA and EPA reform efforts reflect a growing uneasiness among American consumers that regulators aren’t doing enough to ensure the chemicals we encounter every day are safe for human health and development. “Both chemical manufacturers and lawmakers have realized this is something that consumers really care about,” she added.

Testing TPP in Sofas — But Not Nail Polish

Under the Toxic Substances Control Act framework, the EPA has flagged TPP as one of 90 “high-priority” chemicals that it intends to evaluate and regulate ahead of thousands of other chemicals.

The EPA in 2014 identified TPP as a potential hazard due to its high aquatic toxicity, meaning it poses a possible threat to marine life when it reaches waterways. Yet a handful of recent studies have also linked exposure to TPP with reproductive and developmental toxicity, metabolic disruption and other potential health effects in humans.

A 2012 study by South Korean researchers that looked at human cell lines and zebrafish found TPP and other organophosphate flame retardants could alter the balance of estrogen and testosterone, the key female and male hormones. Another study by U.S. researchers from North Carolina and Ohio found that mice exposed to Firemaster 550 — a mixture that contains TPP — experienced weight gain, early onset puberty and heart effects at levels relevant to human exposure. The studies offer clues to how TPP might behave in human bodies, although scientists agree that more testing and research is needed to understand the full effects of short- or long-term exposure.

The EPA will have up to three years to review TPP once it takes up the chemical. Regulators will try to determine if TPP is hazardous to humans and the environment, and if it is, at which concentrations, periods of exposures and uses. The EPA could then try to ban the material or restrict its uses in the types of products that the agency regulates. But since the EPA doesn’t regulate cosmetics, that decision will not directly affect the ways that nail polishes are produced and sold under the FDA’s watch, even as consumer advocates grow more concerned about TPP’s use in cosmetics.

A recent study by Duke University and Environmental Working Group found evidence of the chemical in women who had recently painted their nails. More than two dozen participants had a metabolite of TPP in their bodies just 10 to 14 hours after applying polish. Their levels of diphenyl phosphate, which forms as the body processes TPP, increased nearly sevenfold, the researchers said in an October 2015 paper.

Subramanian of Vegan Beauty Review said it was this study that alerted her to the potential risks of TPP in nail polish.

“I was pretty aware of most of the common toxic chemicals found in conventional store-bought nail polishes, but TPP honestly hadn’t been on my radar until the study came out,” she said. “Right after this story broke, I swore off TPP in a heartbeat.”

Cutting out all products that contain TPP requires a bit of homework. More than 1,500 nail polishes and treatments contain the compound, or about half of the 3,000-plus nail products listed in Environmental Working Group’s Skin Deep cosmetics database. That doesn’t include the nail polishes that may contain undisclosed amounts of TPP.

FDA regulations require cosmetics (as well as food and drink) companies to list product ingredients on the bottle or packaging, in order of highest volume to lowest. In some cases, though, manufacturers can lump specific ingredients together as “fragrances” in order to protect trade secrets. If TPP or other plasticizers are used to help with a product’s scent, then those ingredients might be listed within the catch-all group.

The Personal Care Products Council, which represents leading nail polish manufacturers, said consumers have no reason to worry about TPP in their nail polish. The trade group said the Duke-Environmental Working Group research is “speculative, misleading and does not use sound science to assess the safety of an ingredient which has a long and well-documented history of safe use,” according to the emailed statement. “The makers of nail polish stand behind their products.”

Revlon, however, which uses TPP in some of its nail enamels, said it was in the process of reformulating its products to exclude TPP entirely. “This is a part of our ongoing commitment to continuously improve upon our product formulas,” a Revlon spokeswoman said.

Consumers 'Need to Be the Hawks'

Beyond requiring companies to list ingredients on labels, the FDA is broadly limited in what it can do to regulate cosmetics under a 1938 law.

The FDA is not allowed to ask companies to test products for safety or provide safety data about the ingredients. The agency is also prohibited from regulating most cosmetics and beauty supplies before they hit store shelves. Only after a product hits the market — and the FDA or consumers finds evidence of health risks — can regulators step in to require additional labeling or take other measures.

Subramanian said she was upset that the FDA isn’t even allowed to regulate terms like “all-natural” or “non-toxic” that are increasingly popping up on labels as manufacturers market to consumers’ fears of harmful ingredients.

Lauren Sucher, a spokeswoman from the FDA, said the agency tries to find “as many ways as possible” to gather and share information about cosmetics and other personal care products. “We try to be proactive and work with both industry and consumers,” she said.

For example, the FDA has set up a program for companies to voluntarily share data that the agency can’t force them to provide. The FDA regularly reviews peer-reviewed scientific literature on chemicals in the products it regulates, and it can perform its own studies or monitoring of products currently on the market. The FDA’s own review of phthalates, which are also suspected endocrine disruptors and used in nail polishes, concluded that “it’s not clear what effect, if any, phthalates have on human health.”

Cosmetics manufacturers can also exchange safety information and scientific literature through the Cosmetics Ingredient Review, an industry-sponsored panel of scientific and medical experts. The FDA says it takes the panel’s reviews into consideration when evaluating the safety of cosmetic ingredients.

Now that Obama has signed the reforms to EPA’s Toxic Substances Control Act, consumer safety advocates are turning their focus to overhauling the FDA’s 78-year-old cosmetics regulations. Sens. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., and Susan Collins, R-Maine, in April 2015 co-sponsored the Personal Care Products Safety Act, which was referred to the Senate’s health committee in April.

The bill would allow the FDA for the first time to review the safety of ingredients used in thousands of bath and beauty products, starting with formaldehyde-releasing chemicals and a long-chained paraben that may pose risks to human health and development. The act would also require cosmetics companies to disclose all the ingredients they use to the FDA and to register their facilities with the agency, enabling it to inspect factories and collect records.

Personal care manufacturers like Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble and Unilever — all of which support the bill — would pay the FDA $20.6 million in annual fees to help fund cosmetic safety activities.

Benesh of Environmental Working Group said the momentum surrounding the EPA’s toxics reforms could embolden the push to transform regulations of nail polishes, manicuring products and all the types of creams, soaps and powders that Americans put on their bodies.

“The movement to reform [EPA’s law] and this cosmetics bill are both coming from the same place of consumers demanding their right to know and to have a better regulatory regime in place to keep people safe,” Benesh said. But she added, “Even if we are able to get more federal regulations and oversight, consumers are still going to need to be the hawks and push for the changes they want to see.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.