Why 2016 Candidates Are Using Their First Names On The Campaign Trail

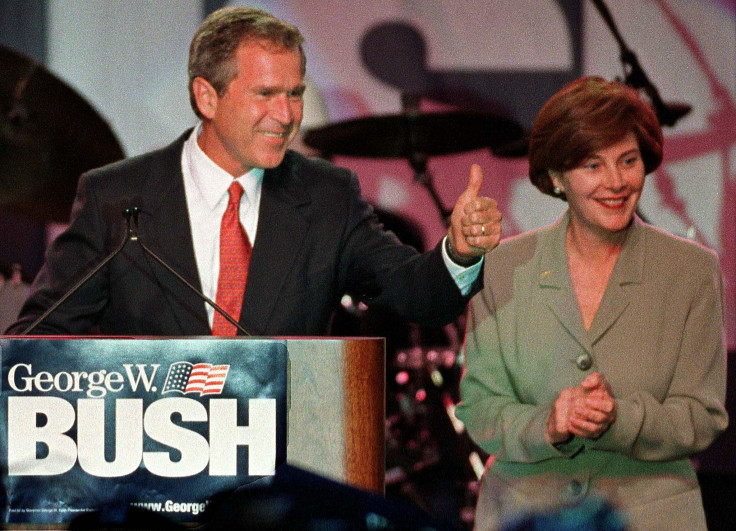

If one were to look at side-by-side snapshots of the electoral campaigns conducted by two brothers seeking the same office 16 years apart, one thing would be easily noticeable about the logos designed to promote George W. Bush in 1999 and Jeb Bush in 2015. Even though their family is one of the most recognizable political powers in U.S. history, the former adorned his campaign materials with the family name displayed prominently, while the latter brands all his merchandise with "Jeb!"

A striking number of 2016 U.S. presidential campaigns have made the decision to use the first name of their candidates on most or all of the merchandise, and that choice is anything but an accident. It shows independence from traditional power structures. It makes the candidate approachable, a friend. And it shows that social media has changed national political campaigns, campaign strategists said.

Whereas names such as Bush, Clinton, Kerry and Reagan traditionally have jutted out from American lawns as election seasons have drawn near, things are a bit different this cycle. Along with Bush, presidential candidates such as former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, former Hewlett-Packard Co. CEO Carly Fiorina, Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky and Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida all have shown the willingness to shed their surnames on the campaign trail.

"It's something [campaigns] think about. They think about it a lot. It's something that they test, mostly in focus groups," said David Walker, a vice president at Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research, a Democratic polling firm that worked on former President Bill Clinton's 1992 presidential campaign and former President Nelson Mandela's historic 1994 campaign in South Africa. "Politically, they're trying to bridge the divide between the elected and the electorate, which is massive."

That divide has grown recently. While it is not at an all-time low, public trust in government is at a low point compared with half a century ago, according to historical polling data at the Pew Research Center. The public trusted government by an overwhelming majority in 1964, when 77 percent of respondents expressed the sentiment. Fifty years later, the percentage of people who said they trusted government had dropped to 24 percent. Want more proof? This year, approval of Congress reached an all-time low: 7 percent.

With that decline in trust, the political wisdom of referring to candidates by their formal titles also appears to have lost its luster. Voters aren't interested in established candidates in the American political system, an idea that is clear when looking at the current front-runners in the race for the Republican presidential nomination: Atop national polls are real-estate mogul Donald Trump, retired neurosurgeon Dr. Ben Carson and Fiorina, none of whom has ever held elected office.

"It used to be that if you ran for president, you would always say 'Sen. Ted Cruz' or 'Sen. Marco Rubio' or 'Sen. John F. Kennedy,'" noted Rick Wilson, a Republican media consultant in Florida. "Your service in government was a positive calling card, and now it's a lot less the case."

Political experts indicated there are varying reasons why a candidate might make the ultimate decision to pull the trigger on a brand that will stick with him or her throughout what could be a long and grueling campaign by spending the cash to put a name on signs and T-shirts. In focus groups, there's a lot of listening: "What does the focus group start calling the candidate? They naturally call him Marco like they've known him for a while? Great. How do we differentiate ourselves from the Bush family name? Let's try Jeb."

There's also an increased premium in appealing to voters in a relatable way. The primary season, and the rules associated with delegates and voting, has changed a lot in the past 40 years, according to William Howell, a professor in American politics at the University of Chicago. Forty years ago, some primary states didn't even hold public votes. All decisions were made by party bosses, and delegates strategized behind the scenes on how to get their guy the nomination with whatever grouping of their peers could be scraped together -- it didn't much matter then whether the candidate was relatable to the average voter. As the primary process became more democratic, that changed. Candidates were forced to show they weren't much different from primary voters, even when were running for president.

"You can't just sort of meet for lunches with the power brokers; they've got to get out in the field and talk to the people," Howell said of candidates nowadays. "They're all looking for ways to do that and be appealing, and using first names is one such way."

Social media has made being relatable even more important. Facebook Inc. and Twitter Inc., with market capitalizations of $261.5 billion and $17.35 billion, respectively, are assuming increasingly larger places in the financial world and people's personal lives. It isn't just advertising that provides the value in using these platforms: Celebrities and politicians see their flagship sites as good forums to interact with supporters, too. As they engage on these digital platforms, the nature of the media and the sense of intimacy they afford pushes candidates to be more familiar.

"It's not Mr. James; it's LeBron. It used to be Joe Namath, not Joe," the pollster Walker said. "Because of the rise of social media, there's a certain intimacy between [the] famous and the public out there."

Whether a candidate comes from a so-called political dynasty such as the Clinton family or is a newcomer to the national political scene such as Paul, finding a way to stick with voters in a relatable and memorable way is important. At least, that's what campaigns employing a first-name-first strategy bet will happen. Small things add up on the trail -- the color of your tie, the type of shirt you wear, the name you go by -- even if each might not be a make-or-break issue on its own. In a crowded field, however, the cumulative weight can have an impact.

"It's not a cynical way of presenting it. It’s just the reality on the ground. And the notion that this is all about who has the best policy ideas or who is the smartest person" is naive, said Kenneth Mayer, a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin. "You add to that mix, and you still have [a crowded field of Republican] candidates in the race. It's not going to be a matter of doing policy statements; it's going to be a matter of who can connect with voters and form a positive impression of: This is a person who can be trusted."

Follow me on Twitter: @ClarkMindock

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.