Why Are Cancer Drugs So Expensive? Wasted Medicine Amounts To $3 Billion Annually, Report Finds

Amid a continuing heated debate over how to bring down skyrocketing drug costs in the United States, a new report has found that $3 billion in cancer drugs goes to waste every year, for one very simple reason: Most of those medicines are distributed in vials that contain more of the drug than the average patient needs.

Researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and at the University of Chicago published these findings Tuesday in a report in the BMJ, previously known as the British Medical Journal. In publishing their findings, the researchers called for an end to regulatory standards in the U.S. that allow drugmakers to increase their profits by distributing these drugs in single-dose packages.

"These drugs must be either administered or discarded once open, and because patients’ body sizes are unlikely to match the amount of drug included in the vial, there is nearly always some left over," the researchers — Peter Bach, Raymond Muller, Geoffrey Schnorr and Leonard Saltz from Memorial Sloan Kettering, and Rena Conti of the University of Chicago — pointed out. Yet the medicine that remains must still be paid for, even when it's tossed out. Many of the drugs, the report noted, cost thousands of dollars per vial.

Bortezomib, to treat multiple myeloma, which causes cancer in bone marrow, for instance, is available in the United States only in vials of 3.5 milligrams. But the average dose needed for a patient is 2.5 milligrams, according to the researchers' calculations. As a result, nearly a third of bortezomib in the U.S., worth $309 million, goes unused.

Overspending driven by oversized single dose vials of #cancer drugs, reports @peterbachmd https://t.co/DXa9XHJBQ7 pic.twitter.com/6ynz5W0wiu

— BMJ (@bmj_company) March 1, 2016

Few doctors and hospitals use these leftover drugs to treat other patients, because regulations require that drugs can be shared only within six hours of opening, and only in specialized pharmacies.

The researchers focused their study on the top 20 cancer drugs in the United States by projected 2016 sales, using Medicare claims and data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to calculate how much of these drugs were left over after vials were opened and the medicine administered. They estimated that overall, this proportion ranged from 1 to 33 percent. For rituximab, an injection to treat non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, the wasted 7 percent of its $3.6 billion in sales translated to $254 million.

The researchers looked specifically at the United States, where the government does not have a say in negotiating drug prices, unlike in other Western countries. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the multiple myeloma drug bortezomib is sold is 1 milligram vials rather than the 3.5 milligram versions available in the United States.

Pharmaceutical companies are not the only entities to rake in profits from this system. The hospitals and doctors that charge for these drugs will "almost certainly" earn more than $1 billion in markups as well in 2016, the researchers estimated. The federal government, through its Medicare programs, and commercial insurers alike cover the costs, as do patients.

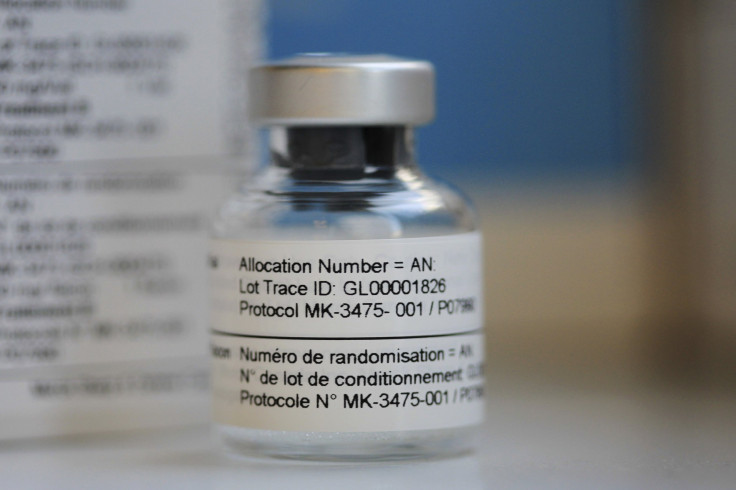

Waste in Cancer Drugs Costs $3B/Yr (interesting focus on Keytruda)https://t.co/1QDC83fcO0https://t.co/HqHQROvzuu pic.twitter.com/nL0VPumI4j

— Andy Biotech (@AndyBiotech) March 1, 2016

Although their study focused on oncology drugs, the researchers noted: "The problem of mismatched single-dose vials and doses is not unique" to cancer. Portions of asthma drugs and medicines for autoimmune diseases, for instance, are similarly excessive, compared with the actual dosages needed.

As political candidates and politicians alike argue over the quickest and most effective way to bring down drug prices, the researchers suggested that they had found one straightforward way of eliminating waste and lowering costs: “Drug companies are quietly making billions forcing little old ladies to buy enough medicine to treat football players, and regulators have completely missed it,” Peter Bach, one of the study's co-authors and the director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering, told the New York Times. “If we’re ever going to start saving money in healthcare, this is an obvious place to cut.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.